Brahma Chellaney, Open Magazine

US President Donald Trump’s India visit, with his wife Melania, is significant for several reasons, including the fact that this is his first overseas trip since his acquittal earlier this month in the impeachment trial. Like his host, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Trump has become a lightning rod in his country’s political churn. The hyper-partisan domestic politics in the US and India has been plumbing new depths, poisoning the discourse in both countries.

To be sure, the US and India are not the only democracies weighed down by a spike in polarization or by incivility in political discourse. Partisanship has become more intense than ever in a number of other democracies.

However, bitter partisanship and a national divide stand out in the US and India. Nothing illustrated this better than the vote in the US House of Representatives to impeach Trump along party lines, without the support of a single Republican member. Impeachment should never have proceeded without broad, bipartisan support. Even Trump’s Senate acquittal was essentially along party lines.

Trump and Modi, despite their very different backgrounds, have a lot in common politically. Each has become an increasingly polarizing figure at home. Citizens either love or loathe them. Like the Washington establishment’s antipathy to Trump, the privileged New Delhi elite has never accepted Modi. This explains why Modi’s re-election in a landslide victory nine months ago has only helped to solidify the polarization in the country.

In fact, Trump and Modi are accused by their critics at home of behaving like authoritarian strongmen. The truth is that American and Indian democracies are robust enough to deter authoritarian creep. Modi’s critics, for example, only underscore India’s robust freedoms by hurling — without fear of reprisal — all sorts of accusations at him, including that he is striking “a historic blow” to Indian democracy and turning India into a “Hindu Pakistan”.

In both the US and India, the widening schism between the pro- and anti-Trump/Modi forces — who, segregated in their own ideological silos, inhabit increasingly separate realities about virtually everything — is strengthening divisive politics. This, in turn, has made politics increasingly vitriolic.

Against this background, is it any surprise that Trump decided, even before the Senate acquittal, to meet his friend Modi in India, including in the latter’s home base of Ahmedabad? Trump’s visit to the world’s largest democracy was overdue, given that he has already been to the other major Asian countries, such as China and Japan. His India visit, significantly, is a solo trip.

Trump shares with Modi a love for big audiences and theatrics. This is why Modi decided to honour Trump at an event to be attended by some 110,000 people at the world’s biggest cricket stadium in Ahmedabad. Last September, Modi and Trump had walked hand-in-hand at a rock-concert-like event, called “Howdy, Modi”, at the NRG Stadium in Houston.

When Trump joined Modi’s public rally in Houston, which was attended by 59,000 Indian-Americans and a number of American congressmen and senators, it underscored the growing closeness of the US-India relationship. Now the Ahmedabad event and Trump’s meetings in New Delhi, as the White House has said, will “further strengthen the US-India strategic partnership and highlight the strong and enduring bonds between the American and Indian people”.

With Trump’s focus on getting re-elected in November, his India visit will also endear him to the increasingly influential and wealthy Indian-Americans, who now number about 4 million, or 1.3% of the total US population. They not only matter in some of the swing states for the presidential election, but also are important political donors.

The rationale for closer ties

The strengthening American ties with democratic India have assumed greater geopolitical importance for Washington, given that US policies in this century have counterproductively fostered a partnership between the world’s largest nuclear power, Russia, and the world’s second-largest economy, China. But during the Cold War years, US President Richard Nixon’s administration, seeking to avoid confronting Russia and China simultaneously, forged strategic cooperation with the weaker party, China, in order to balance the stronger Soviet Union. China’s co-option played an important role in the West’s ultimate triumph in the Cold War. Today, however, US policy has helped build a growing Sino-Russian nexus.

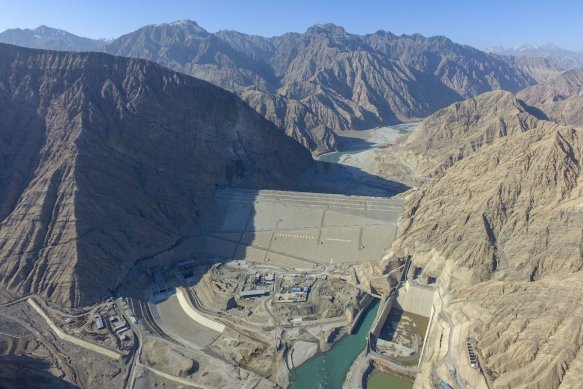

According to the last US national security strategy report, America welcomes “India’s emergence as a leading global power and stronger strategic and defence partner”. India is pivotal to the Trump administration’s strategy of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” region, a concept originally authored by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. India occupies a critical position in the western part of the Indo-Pacific: It has a coastline of 7,500 kilometres, with more than 1,380 islands and over two million square kilometres of Exclusive Economic Zone.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, during his New Delhi visit last June, said: “We must understand that not only is the US important to India but India is very important to the US”. India meshes well with Trump’s export plan to create large numbers of well-paid American jobs. As Trump told the Houston rally, “We are working to expand American exports to India, one of the world’s fastest-growing markets”.

Moreover, the US and India are natural allies in countering the growing global scourge of jihadist terrorism. At Modi’s Houston rally, Trump said: “Today, we honour all of the brave American and Indian military service members who work together to safeguard our freedom. We stand proudly in defence of liberty, and we are committed to protecting innocent civilians from the threat of radical Islamic terrorism”.

In the way Modi casts himself as India’s “chowdikar” (protector) safeguarding the country’s frontiers from terrorists and other subversives, Trump has prioritized border defences to keep out those that “threaten our security”. As Trump declared at the Houston rally, to the delight of Indians, “Border security is vital to the US. Border Security is vital to India. We understand that”.

Considering such a congruent interest, US-India counterterrorism cooperation ought to be robust, mutually beneficial and mutually reinforcing, while America’s relationship with Pakistan by now should have come apart. However, while US-India counterterrorism cooperation is growing, the Trump administration has helped secure an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout for cash-strapped Pakistan and opposed that country’s inclusion on the blacklist of the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Trump has also drawn a perverse equivalence between the terrorism-exporting Pakistan and its victim India. Indeed, according to the White House, Trump, at his meeting with Modi in New York last autumn, privately “encouraged Prime Minister Modi to improve relations with Pakistan”, and then publicly said, “Those are two nuclear countries. They’ve got to work it out”. Geopolitically, Pakistan remains important for America’s regional interests, including in relation to Afghanistan, Iran and India.

Consider a more fundamental factor: Whereas the US significantly aided China’s economic rise from the 1970s by co-opting Beijing into its anti-Soviet strategy, Washington today has no such compelling geostrategic motivation to assist India’s rise. The US does not feel as threatened by Sino-Russian cooperation as it did from the Soviet-Chinese partnership during the Cold War, largely because Russia now appears in irreversible decline. Indeed, the more Russia has moved closer to China, the more it has eroded its influence, as in Central Asia.

India is important for the US because of its large and rapidly growing market and its strategic location in the Indo-Pacific. It is the only resident power in the western part of the Indo-Pacific that can countervail China’s military and economic moves.

The phrase “Indo-Pacific”, as then US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson alluded to, was intended to emphasize that the US and India are “bookends” in that region. Recently, however, the Trump administration has redefined the Indo-Pacific as a region extending to the Persian Gulf, in keeping with its fixation on Iran. This is one reason why its “free and open Indo-Pacific” strategy has still to gain traction.

The US views an economically booming India as good for American businesses. Trump in New Delhi will meet with top executives of Indian companies that are major investors in the US. For example, Mahindra and Mahindra has announced it is investing $1 billion in the US, while the Tata Group is one of the largest multinationals operating from American soil. Today, the transactional elements in the US-Indian partnership, unfortunately, have become more conspicuous than the geostrategic dimensions.

Trump, a friend of India?

Trump’s foreign policy has centred on a strange mix of avowed isolationism, impulsive interventionism and tough negotiations even with friends. Trump’s unilateralism and transactional approach have reflected a belief that the US can pursue hard-edged negotiations with friends without imperilling its broader strategic interests. This approach has rattled many of America’s longstanding allies.

In India, however, Trump still enjoys a high positive rating. He may have privately mocked Modi’s English pronunciation but has developed a personal rapport with him.

Successive US administrations, in fact, have been good at massaging India’s collective ego, with statements like “the growing partnership between the world’s oldest democracy and largest democracy”. Pompeo, for example, declared, “Modi hai to sab mumkin hai”. Pompeo’s praise of US-India ties, however, has failed to obscure the differences and disputes resulting from the Trump administration’s unilateral actions and demands.

Despite his bonhomie with Modi, Trump, for example, has waged a mini-trade war against India, although in the shadow of the much larger US-China trade war. He has raised duties on 14.3% of India’s exports to the US and imposed a restrictive visa policy to squeeze the huge Indian information-technology industry. In March 2018, he increased tariffs on steel and aluminium from India.

Indeed, no sooner had Modi’s second term started in May 2019 than Trump announced the termination of India’s preferential access to the US market by expelling the country from the Generalized System of Preferences. Soon thereafter, the office of the United States Trade Representative warned of a Section 301 investigation against India if trade differences were not sorted out.

The array of US demands on India have ranged from lifting price controls on heart stents, knee implants and other medical devices to relaxing e-commerce rules. Unlike China, where homegrown players like Alibaba have cornered the e-commerce market, India has allowed Amazon and Walmart to establish a virtual duopoly over its e-commerce. Would the US, like India, permit two foreign companies to control its e-commerce?

Some US demands actually represent gross insensitivity. For example, the US has pressured India — where many citizens are vegetarian — to open its market to American cheese and other products from cows that have been raised on feed containing bovine and other animal by-products. This would offend the religious and cultural sensitivities of many Indians, especially Hindus who do not consume beef or its by-products. For India, the routine administration of antibiotics to healthy cows in the US also raises public-health concerns, including the possible spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Despite Modi’s unmistakably US-friendly foreign policy, the Trump administration has mounted pressure on India not just on trade but also on other flanks, including oil and defence. For example, not content with the US having emerged as the largest seller of arms to India, Washington has sought to lock that country as America’s exclusive arms client by using the threat of sanctions to deter it from buying major Russian weapons, including the S-400 air defence system.

The US said last July, after it terminated India’s sanctions waiver for importing Iranian oil, that it was “highly gratified” by New Delhi’s compliance with sanctions against Iran. It is really one-sided gratification. The US sanctions have driven up India’s oil-import bill by stopping it from buying crude from next-door Iran. In fact, the US has been supplanting Iran as an important source of crude oil and petroleum products for India, the world’s third-largest oil consumer after America and China. But the US oil and petroleum exports to India come at a higher price than from Iran.

A transportation corridor to Afghanistan that India is building via Iran, bypassing Pakistan, shows that New Delhi’s relationship with Tehran is more than just about oil. US policy, however, is pushing India out of Iran while letting China fill that space. China has deepened its ties with Tehran: It has continued to import Iranian oil through private companies and invest billions of dollars in Iran’s oil, gas and petrochemical sectors.

A US-India trade deal, however framed, is unlikely to help fully lift US pressure on India, whose economy is now growing at the slowest rate in years, with unemployment at a 45-year high. Some of Trump’s trade-related demands would help open the Indian market further to Chinese dumping, thereby widening India’s already-huge trade deficit with China. Indeed, lumping the world’s largest democracy with America’s main strategic competitor, Trump is pushing to terminate India’s and China’s developing-nation status at the World Trade Organization.

Meanwhile, Trump’s policy, by seeking to normalize US relations with Pakistan, has helped ease international pressure on that country to take concrete, verifiable actions to root out the 22 UN-designated terrorist entities that it harbours. Pakistan, for its part, has shown that there are no significant economic consequences for being on the FATF’s “grey” list. Just last summer it secured a large IMF bailout package with US backing. It has also received billions of dollars in emergency loans from China, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

The FATF admits that Pakistan has failed to meet the group’s major parameters against terror financing. Yet, with the US loath to exercise the leverage it has to reform a scofflaw Pakistan, that country has not been moved from the FATF’s “grey” to “black” list.

Modi, speaking at the UN General Assembly last September, warned against the politicization of international counterterrorism mechanisms. The global war on terror, however, has always been about geopolitics. Otherwise, why would the US align with Al Qaeda in Syria against President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, or why would China seek to shield the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed terrorists based in Pakistan?

Geopolitical factors, including Trump’s effort to strike a Faustian bargain with the Pakistan-backed Afghan Taliban, also explain why the US president, despite a Kashmir mediation offer being a red rag to India, has repeatedly offered to mediate that conflict. In fact, Trump has rewarded Pakistan with IMF and other aid and then offered to mediate the Kashmir conflict. Likewise, Trump first green-lighted Turkey’s military assault on America’s Kurdish allies and then offered to broker peace between the Turks and Kurds, saying “I hope we can mediate”.

Trump’s mediation offer has little to do with finding a way to resolve the Kashmir problem; it is more about making the US a stakeholder. As long as Indian policy seeks American assistance to rein in Pakistan, instead of tackling the problem directly, the US will strive to make itself a stakeholder in the India-Pakistan relationship.

Still, the US is a key partner for India

Despite bilateral differences on several important subjects, the US remains a key partner for India. Accelerating cooperation and collaboration with the US has been Modi’s signature foreign-policy initiative. Under Modi, India has been gravitating closer to the US in ways that do not undermine India’s longstanding partnership with Russia or provoke retribution from China.

The deepening cooperation has led to a series of bilateral agreements in recent years. In 2016, the US and India signed a logistics agreement on access to each other’s military base. A 2018 accord allows US and Indian forces to share encrypted communications. And a 2019 agreement permits each other’s private companies to transfer classified defence technologies.

Furthermore, the frequency and complexity of US-India military exercises have increased. Last November, the US military held its first joint exercises with all three of India’s military branches — the army, the navy and the air force.

To be sure, US-India military collaboration poses some challenges. The US has little experience in developing close military collaboration with countries that are not its treaty-based allies. All its major military partners are its allies in a patron-client framework. India, however, is its strategic partner (not an ally) that expects some degree of equality. Yet, in opposing India’s purchase of the S-400 surface-to-air missile system from Russia, the US has cited “military interoperability” issues, as if India were a NATO member or its formal ally like Turkey, which is also acquiring the S-400.

India’s long legacy of dependence on Russia for strategic weapons — ranging from a nuclear-powered submarine to an aircraft carrier — will change only through a robust Indo-US partnership, not through threats or sanctions. However, last year’s failure to pass an amendment in the US Congress to give India NATO-equivalent status under the US Arms Export Control Act (AECA) for the purposes of arms sales represents a setback for building a steady US-India military partnership.

Had it been enacted in its original form, the amendment (introduced by Congressman Brad Sherman and co-sponsored by several other representatives) would have provided India the same status as America’s NATO allies as well as Israel, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and Japan for AECA-related purposes in relation to arms exports. The original amendment sought to elevate India’s status under the AECA so as to facilitate US arms sales to India in a wider and more forward-looking and timely manner. That would have been in keeping with the imperative to bolster the Indo-US relationship in order to check China’s muscular moves in the Indian Ocean region.

India is ideologically compatible with, and strategically central, to US interests. For New Delhi, a robust relationship with the US is pivotal to long-term Indian interests. Yet, paradoxically, the two countries’ strategic interests diverge in India’s own neighbourhood. The farther one gets from India, the more congruent US and Indian interests become. But closer home to India, the two sides’ interests are divergent, including on how to deal with the Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran challenges.

Against this background, does anybody seriously think that if China staged a 1962-style surprise military attack on India, the Trump-led US will come to India’s aid or even side with India? As it did during the 2017 Doklam standoff, the US would probably chart a course of neutrality in that war.

Take another example: Pakistan used the US-supplied F-16s against India on February 27, 2019, in a cross-border aerial raid following the Indian Air Force’s daring airstrike on a Jaish-e-Mohammed camp in Balakot. Yet, the US chose to look the other way, despite admitting the “presence of US personnel that provide 24/7 end-use monitoring” on the F-16 fleet in Pakistan. Worse still, it rewarded Pakistan with $125 million worth of technical and logistics support services for the F-16s, saying the aid will not affect the “regional balance”.

The bottom line for India is that no friend, including the US, will truly assist it to end Pakistan’s terrorism. When terrorism is directed at just India, the American military will not seek to take out any of the US-designated “global terrorists” in Pakistan. For example, the US has done little more than put a $10 million bounty since 2012 on Lashkar-e-Taiba founder Hafiz Saeed, one of the top terrorist leaders in Pakistan. This is India’s battle to fight and win on its own.

More broadly, a US policy approach that seeks to weaponize tariffs, trade and dollar dominance will compel India to hedge its bets. As the chairman of the US House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Eliot L. Engel, warned last year, the Trump administration, by “attempting to coerce India into complying with US demands on a variety of issues”, has not only “introduced significant friction in our partnership with New Delhi” but also is alienating India.

Henry Kissinger once quipped that “it may be dangerous to be America’s enemy, but to be America’s friend is fatal”. Trump is pursuing his foreign policy as if those words have the ring of truth. At the Houston rally, Trump claimed India has “never had a better friend” than him in the White House. Yet Trump’s transactional approach, which prioritizes short-term gains for the US even at the expense of long-term returns, could be reinforcing Indian scepticism about American reliability. The Modi government, clearly, values robust ties with the US, but such relations cannot be at the expense of India’s own interests.

Make no mistake: India has been a US foreign-policy bright spot. There is strong bipartisan support in Washington for a closer partnership with India. And as Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser Jared Kushner has said, “The relationship between America and India is one with boundless potential”. It is important for both sides to focus on the relationship’s tremendous potential.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including

“Great nations do not fight endless wars,” US President Donald Trump declared in his 2019 State of the Union speech. He had a point: military entanglements in the Middle East have contributed to the relative decline of American power and facilitated China’s muscular rise. And yet, less than a year after that speech, Trump ordered the assassination of Iran’s most powerful military commander, General Qassem Suleimani, bringing the United States to the precipice of yet another war. Such is the power of America’s addiction to interfering in the chronically volatile Middle East.

The US no longer has vital interests at stake in the Middle East. Shale oil and gas have made the US energy independent, so safeguarding Middle Eastern oil supplies is no longer a strategic imperative. In fact, the US has been supplanting Iran as an important source of crude oil and petroleum products for India, the world’s third-largest oil consumer after America and China. Moreover, Israel, which has become the region’s leading military power (and its only nuclear-armed state), no longer depends on vigilant US protection.

The US does, however, have a vital interest in resisting China’s efforts to challenge international norms, including through territorial and maritime revisionism. That is why Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, promised a “pivot to Asia” early in his presidency.

But Obama failed to follow through on his plans to shift America’s foreign-policy focus from the Middle East. On the contrary, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate staged military campaigns everywhere from Syria and Iraq to Somalia and Yemen. In Libya, his administration sowed chaos by overthrowing strongman Muammar el-Qaddafi in 2011. In Egypt, Obama hailed President Hosni Mubarak’s 2011 ouster.

Yet in 2013, when the military toppled Mubarak’s democratically elected successor, Mohamed Morsi, Obama opted for non-intervention, refusing to acknowledge it as a coup, and suspended US aid only briefly. This reflected the Obama administration’s habit of selective non-intervention – the approach that encouraged China, America’s main long-term rival, to become more aggressive in pursuit of its claims in the South China Sea, including building and militarizing seven artificial islands.

Trump was supposed to change this. He has repeatedly derided US military interventions in the Middle East as a colossal waste of money, claiming the US has spent $7 trillion since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. (Brown University’s Costs of War Project puts the figure at $6.4 trillion.) “We have nothing – nothing except death and destruction. It’s a horrible thing,” Trump said in 2018.

Furthermore, the Trump administration’s national-security strategy recognizes China as a “strategic competitor” – a label that it subsequently replaced with the far blunter “enemy.” And it has laid out a strategy for curbing Chinese aggression and creating a “free and open” Indo-Pacific region stretching “from Bollywood to Hollywood.”

Yet, as is so often the case, Trump’s actions have directly contradicted his words. Despite his anti-war rhetoric, Trump appointed war-mongering aides like Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who has been described as a “hawk brimming with bravado and ambition,” and former National Security Adviser John Bolton, who in 2015 wrote an op-ed called “To Stop Iran’s Bomb, Bomb Iran.”

Perhaps it should be no surprise, then, that Trump has pursued a needlessly antagonistic approach to Iran. The escalation began early in his presidency, when he withdrew the US from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal (which Iran had not violated), re-imposed sanctions, and pressured America’s allies to follow suit. Furthermore, since last May, Trump has deployed 16,500 additional troops to the Middle East and sent an aircraft-carrier strike group to the Persian Gulf, instead of the South China Sea. The assassination of Suleimani was part of this pattern.

Like virtually all of America’s past interventions in the Middle East, its Iran policy has been spectacularly counterproductive. Iran has announced that it will disregard the nuclear agreement’s uranium-enrichment limits. Trump’s sanctions have increased the oil-import bill of US allies like India and deepened Iran’s ties with China, which has continued to import Iranian oil through private companies and invest billions of dollars in Iran’s oil, gas, and petrochemical sectors.

Beyond Iran, Trump has failed to extricate the US from Afghanistan, Syria, or Yemen. His administration has continued to support the Saudi-led bombing campaign against Yemen’s Houthi rebels with US military raids and sorties. As a result, Yemen is enduring the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Trump did order troops to leave Syria last October, but with so little strategic planning that the Kurds – America’s most loyal ally in the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) – were left exposed to an attack from Turkey. This, together with his effort to strike a Faustian bargain with the Afghan Taliban (which is responsible for the world’s deadliest terrorist attacks), threatens to reverse his sole achievement in the Middle East: dramatically diminishing ISIS’s territorial holdings.

Making matters worse, after ordering the Syrian drawdown, Trump approved a military mission to secure the country’s oil fields. The enduring oil fixation also led Trump last April to endorse Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, just as Haftar began laying siege to the capital, Tripoli.

The Trump administration is unlikely to change course any time soon. In fact, it has now redefined the Indo-Pacific region as extending “from California to Kilimanjaro,” thus specifically including the Persian Gulf. With this change, the Trump administration is attempting to uphold the pretense that its interventions in the Middle East serve US foreign-policy goals, even when they undermine those goals.

As long as the US remains mired in “endless wars” in the Middle East, it will be unable to address in a meaningful way the threat China poses. Trump was supposed to know this. And yet, his administration’s commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific seems likely to lose credibility, while the cycle of self-defeating American interventionism in the Middle East appears set to continue.

© Project Syndicate, 2019.