China has transformed the Indo-Pacific region’s strategic landscape in just five years. If other powers do not step in to counter further challenges to the territorial and maritime status quo, the next five years could entrench China’s strategic advantages.

BRAHMA CHELLANEY, Project Syndicate

SYDNEY – Security dynamics are changing rapidly in the Indo-Pacific. The region is home not only to the world’s fastest-growing economies, but also to the fastest-increasing military expenditures and naval capabilities, the fiercest competition over natural resources, and the most dangerous strategic hot spots. One might even say that it holds the key to global security.

The increasing use of the term “Indo-Pacific” – which refers to all countries bordering the Indian and Pacific oceans – rather than “Asia-Pacific,” underscores the maritime dimension of today’s tensions. Asia’s oceans have increasingly become an arena of competition for resources and influence. It now seems likely that future regional crises will be triggered and/or settled at sea.

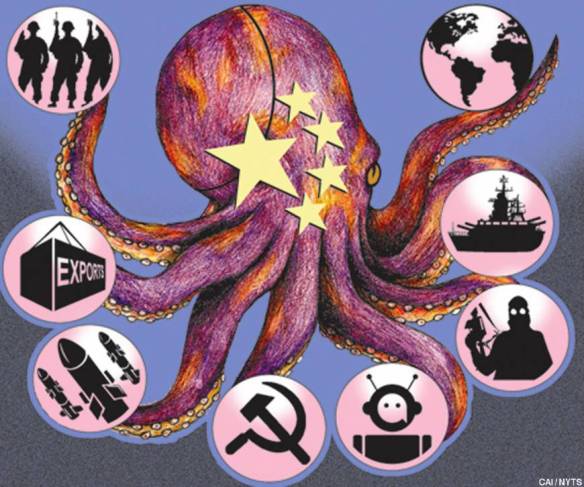

The main driver of this shift has been China, which over the last five years has been working to push its borders far out into international waters, by building artificial islands in the South China Sea. Having militarized these outposts – presented as a fait accompli to the rest of the world – it has now shifted its focus to the Indian Ocean.

Already, China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, which recently expropriated its main port from a Dubai-based company, possibly to give it to China. Moreover, China is planning to open a new naval base next to Pakistan’s China-controlled Gwadar port. And it has leased several islands in the crisis-ridden Maldives, where it is set to build a marine observatory that will provide subsurface data supporting the deployment of nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) and nuclear-powered ballistic missile subs (SSBNs) in the Indian Ocean.

In short, China has transformed the region’s strategic landscape in just five years. If other powers do not step in to counter further challenges to the territorial and maritime status quo, the next five years could entrench China’s strategic advantages. The result could be the ascendancy of a China-led illiberal hegemonic regional order, at the expense of the liberal rules-based order that most countries in the region support. Given the region’s economic weight, this would create significant risks for global markets and international security.

To mitigate the threat, the countries of the Indo-Pacific must confront three key challenges, beginning with the widening gap between politics and economics. Despite a lack of political integration and the absence of a common security framework in the Indo-Pacific, free-trade agreements are proliferating, the latest being the 11-country Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). China has emerged as the leading trade partner of most regional economies.

But booming trade alone cannot reduce political risks. That requires a framework of shared and enforceable rules and norms. In particular, all countries should agree to state or clarify their territorial or maritime claims on the basis of international law, and to settle any dispute by peaceful means – never through force or coercion.

Establishing a regional framework that reinforces the rule of law will require progress on overcoming the second challenge: the region’s “history problem.” Disputes over territory, natural resources, war memorials, air defense zones, and textbooks are all linked, in one way or another, with rival historical narratives. The result is competing and mutually reinforcing nationalisms that imperil the region’s future.

The past continues to cast a shadow over the relationship between South Korea and Japan – America’s closest allies in East Asia. China, for its part, uses history to justify its efforts to upend the territorial and maritime status quo and emulate the pre-1945 colonial depredations of its rival Japan. All of China’s border disputes with 11 of its neighborsare based on historical claims, not international law.

This brings us to the third key challenge facing the Indo-Pacific: changing maritime dynamics. Amid surging maritime trade flows, regional powers are fighting for access, influence, and relative advantage.

Here, the biggest threat lies in China’s unilateral attempts to alter the regional status quo. What China achieved in the South China Sea has significantly more far-reaching and longer-term strategic implications than, say, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, as it sends the message that defiant unilateralism does not necessarily carry international costs.

Add to that new challenges – from climate change, overfishing, and degradation of marine ecosystems to the emergence of maritime non-state actors, such as pirates, terrorists, and criminal syndicates – and the regional security environment is becoming increasingly fraught and uncertain. All of this raises the risks of war, whether accidental or intentional.

As the most recent US National Security Strategy report put it, “A geopolitical competition between free and repressive visions of world order is taking place in the Indo-Pacific region.” And yet while the major players in the region all agree that an open, rules-based order is vastly preferable to Chinese hegemony, they have so far done far too little to promote collaboration.

There is no more time to waste. Indo-Pacific powers must take stronger action to strengthen regional stability, reiterating their commitment to shared norms, not to mention international law, and creating robust institutions.

For starters, Australia, India, Japan, and the US must make progress in institutionalizing their Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, so that they can better coordinate their policies and pursue broader collaboration with other important players like Vietnam, Indonesia, and South Korea, as well as with smaller countries.

Economically and strategically, the global center of gravity is shifting to the Indo-Pacific. If the region’s players don’t act now to fortify an open, rules-based order, the security situation will continue to deteriorate – with consequences that are likely to reverberate worldwide.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Asian Juggernaut, Water: Asia’s New Battleground, and Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis. © Project Syndicate.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Asian Juggernaut, Water: Asia’s New Battleground, and Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis. © Project Syndicate.

US President Donald Trump’s recent decision to freeze some $2 billion in security assistance to Pakistan as punishment for the country’s refusal to crack down on transnational terrorist groups is a step in the right direction. But more steps are needed.

US President Donald Trump’s recent decision to freeze some $2 billion in security assistance to Pakistan as punishment for the country’s refusal to crack down on transnational terrorist groups is a step in the right direction. But more steps are needed.

Moreover, as Sri Lanka’s experience starkly illustrates, Chinese financing can shackle its “partner” countries. Rather than offering grants or concessionary loans, China provides huge project-related loans at market-based rates, without transparency, much less environmental- or social-impact assessments. As US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put it recently, with the BRI, China is aiming to define “its own rules and norms.”

To strengthen its position further, China has encouraged its companies to bid for outright purchase of strategic ports, where possible. The Mediterranean port of Piraeus, which a Chinese firm acquired for $436 million from cash-strapped Greece last year, will serve as the BRI’s “dragon head” in Europe.

By wielding its financial clout in this manner, China seeks to kill two birds with one stone. First, it wants to address overcapacity at home by boosting exports. And, second, it hopes to advance its strategic interests, including expanding its diplomatic influence, securing natural resources, promoting the international use of its currency, and gaining a relative advantage over other powers.

China’s predatory approach – and its gloating over securing Hambantota – is ironic, to say the least. In its relationships with smaller countries like Sri Lanka, China is replicating the practices used against it in the European-colonial period, which began with the 1839-1860 Opium Wars and ended with the 1949 communist takeover – a period that China bitterly refers to as its “century of humiliation.”

China portrayed the 1997 restoration of its sovereignty over Hong Kong, following more than a century of British administration, as righting a historic injustice. Yet, as Hambantota shows, China is now establishing its own Hong Kong-style neocolonial arrangements. Apparently Xi’s promise of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” is inextricable from the erosion of smaller states’ sovereignty.4

Just as European imperial powers employed gunboat diplomacy to open new markets and colonial outposts, China uses sovereign debt to bend other states to its will, without having to fire a single shot. Like the opium the British exported to China, the easy loans China offers are addictive. And, because China chooses its projects according to their long-term strategic value, they may yield short-term returns that are insufficient for countries to repay their debts. This gives China added leverage, which it can use, say, to force borrowers to swap debt for equity, thereby expanding China’s global footprint by trapping a growing number of countries in debt servitude.

Even the terms of the 99-year Hambantota port lease echo those used to force China to lease its own ports to Western colonial powers. Britain leased the New Territories from China for 99 years in 1898, causing Hong Kong’s landmass to expand by 90%. Yet the 99-year term was fixed merely to help China’s ethnic-Manchu Qing Dynasty save face; the reality was that all acquisitions were believed to be permanent.

Now, China is applying the imperial 99-year lease concept in distant lands. China’s lease agreement over Hambantota, concluded this summer, included a promise that China would shave $1.1 billion off Sri Lanka’s debt. In 2015, a Chinese firm took out a 99-year lease on Australia’s deep-water port of Darwin – home to more than 1,000 US Marines – for $388 million.

Similarly, after lending billions of dollars to heavily indebted Djibouti, China established its first overseas military base this year in that tiny but strategic state, just a few miles from a US naval base – the only permanent American military facility in Africa. Trapped in a debt crisis, Djibouti had no choice but to lease land to China for $20 million per year. China has also used its leverage over Turkmenistan to secure natural gas by pipeline largely on Chinese terms.

Several other countries, from Argentina to Namibia to Laos, have been ensnared in a Chinese debt trap, forcing them to confront agonizing choices in order to stave off default. Kenya’s crushing debt to China now threatens to turn its busy port of Mombasa – the gateway to East Africa – into another Hambantota.

These experiences should serve as a warning that the BRI is essentially an imperial project that aims to bring to fruition the mythical Middle Kingdom. States caught in debt bondage to China risk losing both their most valuable natural assets and their very sovereignty. The new imperial giant’s velvet glove cloaks an iron fist – one with the strength to squeeze the vitality out of smaller countries.