When the U.S. aircraft carrier, Carl Vinson, recently made a port call at Da Nang, Vietnam, it attracted international attention because this was the first time that a large contingent of U.S. military personnel landed on Vietnamese soil since the last of the American troops withdrew from that country in 1975. The symbolism of this

port call, however, cannot obscure the fact that the United States, under two successive presidents, has had no coherent strategy for the South China Sea.

It was on President Barack Obama’s watch that China created and militarized seven artificial islands in the South China Sea, while his successor, Donald Trump, still does not seem to have that critical subregion on his radar.

In fact, with Trump focused on North Korea and trade, China is quietly pressing ahead with its expansionist agenda in the South China Sea and beyond. At the expense of its smaller neighbors, it is consolidating its hold by constructing more military facilities on the man-made islands and dramatically expanding its presence at sea across the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific.

It was just five years ago that China began pushing its borders far out into international waters by building artificial islands in the South China Sea. After having militarized these outposts, it has now presented a fait accompli to the rest of the world — without incurring any international costs.

These developments carry far-reaching strategic implications for the vast region stretching from the Pacific to the Middle East, as well as for the international maritime order. They also highlight that the biggest threat to maritime peace and security comes from unilateralism, especially altering the territorial or maritime status quo by violating international norms and rules.

The Indo-Pacific region, which extends from the western shores of the U.S. to eastern Africa and the Persian Gulf, is so interconnected that adverse developments in any of its subregions impinge on wider maritime security. For example, it was always known that if China had its way in the South China Sea, it would turn its attention to the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific. This is precisely what is happening now. An emboldened China has also claimed to be a “near-Arctic state”and unveiled plans for a “polar Silk Road.”

In fact, with the U.S. distracted as ever, China’s land-reclamation frenzy in the South China Sea still persists. China is now using a super-dredger, dubbed by its designers as a “magical island-building machine.”

China’s latest advances are not as eye-popping as its creation of artificial islands. Yet the under-the-radar advances, made possible by the free pass Beijing has got, position China to potentially dictate terms in the South China Sea. Last year alone, China built permanent facilities on 290,000 square meters of newly reclaimed land, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

In this light, U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea cannot make up for the absence of an American strategy. FONOPS neither deter China nor reassure America’s regional allies.

Indeed, China’s cost-free change of the status quo in the South China Sea has resulted in costs for other countries, especially in Asia — from Japan and the Philippines to Vietnam and India. Countries bearing the brunt of China’s recidivism have been left with difficult choices. Japan, of course, has reversed a decade of declining military outlays, while India has revived stalled naval modernization.

China’s sprawling artificial islands that now double as military bases are like permanent aircraft carriers, whose potential role extends to the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific.

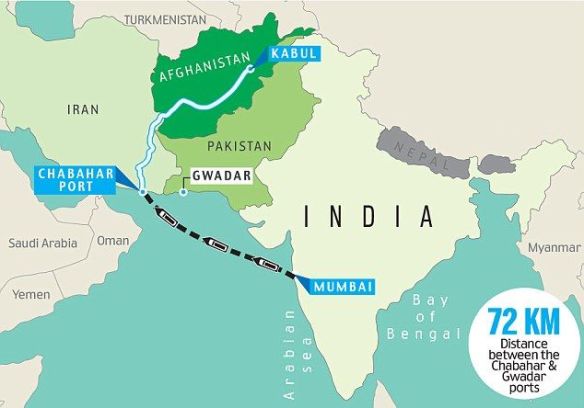

Beijing’s growing strategic interest in the Indian Ocean region has been highlighted by its establishment of its first overseas military base at Djibouti, its deployment of warships around Pakistan’s Chinese-built Gwadar port, and its acquisition of Sri Lanka’s strategically located Hambantota port under a 99-year lease. China is also acquiring a 70 percent stake in Myanmar’s deepwater Kyaukpyu port. A political crisis in the Maldives, meanwhile, has helped reveal China’s quiet acquisition of several islets in that heavily indebted Indian Ocean archipelago.

Against this background, the rapidly changing maritime dynamics in the Indo-Pacific not only inject strategic uncertainty but also raise geopolitical risks.

Today, the fundamental choice in the region is between a liberal, rules-based order and an illiberal, hegemonic order. Few would like to live in an illiberal, hegemonic order. Yet this is exactly what the Indo-Pacific will get if regional states do not get their act together.

There is consensus among all important players other than China for an open, rules-based Indo-Pacific. Playing by international rules is central to peace and security. Yet progress has been slow and tentative in promoting wider collaboration to advance regional stability and power equilibrium.

For example, the institutionalization of the Australia-India-Japan-U.S. “Quad” has yet to take off. The Quad, in fact, remains largely aspirational. In this light, the idea of a “Quad plus two” to include France and Britain seems overly ambitious at this stage.

If and when the Quad takes concrete shape, Britain and France could, of course, join. They both have important naval assets in the Indo-Pacific. During French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent New Delhi visit, France and India agreed to reciprocal access to each other’s naval facilities, on terms similar to the U.S.-India Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement.

Unless the Quad members start coordinating their approaches to effectively create a single regional strategy and build broader collaboration with other important players, Indo-Pacific security could come under greater strain.

If, under such circumstances, Southeast Asia — a region of 600 million people — is coerced into accepting Chinese hegemony, it will have a cascading geopolitical impact in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. China has employed a dual strategy of inducement and coercion to divide and manage the countries of Southeast Asia.

In the South China Sea, China is unlikely to openly declare an air defense identification zone as it did in the East China Sea. Rather it is expected to seek to enforce an ADIZ by gradually establishing concentric circles of air control after it has deployed sufficient military assets on the man-made islands and consolidated its hold over the subregion.

China could also declare “straight baselines” in the Spratlys, as it did in the Paracels in 1996. Such baselines connecting the outermost points of the Spratly island chain would seek to turn the sea within, including features controlled by other nations, into “internal waters.”

To thwart China’s further designs in the South China Sea and its attempts to change the maritime status quo in the Indian Ocean and the East China Sea, a constellation of democratic states linked by interlocking strategic cooperation — as proposed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe — has become critical to help institute power stability. The imperative is to build a new strategic equilibrium, including a stable balance of power.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including the award-winning “Water: Asia’s New Battleground.”

© The Japan Times, 2018.

India is directly in the crosshairs of the new US extraterritorial sanctions targeting Russia and Iran. India is already suffering the unintended consequences of President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal — a pullout that has spurred higher oil-import bills, the rupee’s weakening against the US dollar, and increased foreign-exchange outflows. This is just the latest financial hit India has suffered since 2005 when New Delhi, under US persuasion, voted against Iran in the International Atomic Energy Agency’s governing board, prompting Tehran to cancel a long-term LNG deal favourable to India.

India is directly in the crosshairs of the new US extraterritorial sanctions targeting Russia and Iran. India is already suffering the unintended consequences of President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal — a pullout that has spurred higher oil-import bills, the rupee’s weakening against the US dollar, and increased foreign-exchange outflows. This is just the latest financial hit India has suffered since 2005 when New Delhi, under US persuasion, voted against Iran in the International Atomic Energy Agency’s governing board, prompting Tehran to cancel a long-term LNG deal favourable to India.

The world’s leading democracy, the United States, is looking increasingly like the world’s biggest and oldest surviving autocracy, China. By pursuing aggressively unilateral policies that flout broad global consensus, President Donald Trump effectively justifies his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping’s longtime defiance of international law, exacerbating already serious risks to the rules-based world order.

China is aggressively pursuing its territorial claims in the South China Sea – including by militarizing disputed areas and pushing its borders far out into international waters – despite an international arbitral ruling invalidating them. Moreover, the country has weaponized transborder river flows and used trade as an instrument of geo-economic coercion against countries that refuse to toe its line.

The US has often condemned these actions. But, under Trump, those condemnations have lost credibility, and not just because they are interspersed with praise for Xi, whom Trump has called “terrific” and “a great gentleman.” In fact, Trump’s behavior has heightened the sense of US hypocrisy, emboldening China further in its territorial and maritime revisionism in the Indo-Pacific region.

To be sure, the US has long pursued a unilateralist foreign policy, exemplified by George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq and Barack Obama’s 2011 overthrow of Muammar el-Qaddafi’s regime in Libya. Although Trump has not (yet) toppled a regime, he has taken the approach of assertive unilateralism several steps further, waging a multi-pronged assault on the international order.

Almost immediately upon entering the White House, Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an ambitious 12-country trade and investment agreement brokered by Obama. Soon after, Trump rejected the Paris climate agreement, with its aim to keep global temperatures “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, making the US the only country not participating in that endeavor.

More recently, Trump moved the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, despite a broad international consensus to determine the contested city’s status within the context of broader negotiations on a settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As the embassy was opened, Palestinian residents of Gaza escalated their protests demanding that Palestinian refugees be allowed to return to what is now Israel, prompting Israeli soldiers to kill at least 62 demonstrators and wound more than 1,500 others at the Gaza boundary fence.

Trump shoulders no small share of the blame for these casualties, not to mention the destruction of America’s traditional role as a mediator of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The same will go for whatever conflict and instability arises from Trump’s withdrawal from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal despite Iran’s full compliance with its terms.

Trump’s assault on the rules-based order extends also – and ominously – to trade. While Trump has blinked on China by putting on hold his promised sweeping tariffs on Chinese imports to the US, he has attempted to coerce and shame US allies like Japan, India, and South Korea, even though their combined trade surplus with the US – $95.6 billion in 2017 – amounts to about a quarter of China’s.

Trump has forced South Korea to accept a new trade deal, and has sought to squeeze India’s important information technology industry – which generates output worth $150 billion per year – by imposing a restrictive visa policy. As for Japan, last month Trump forced a reluctant Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to accept a new trade framework that the US views as a precursor to negotiations on a bilateral free-trade agreement.

Japan would prefer the US to rejoin the now-Japan-led TPP, which would ensure greater overall trade liberalization and a more level playing field than a bilateral deal, which the US would try to tilt in its own favor. But Trump – who has also refused to exclude permanently Japan, the European Union, and Canada from his administration’s steel and aluminum tariffs – pays no mind to his allies’ preferences.

Abe, for one, has “endured repeated surprises and slaps” from Trump. And he is not alone. As European Council President Donald Tusk recently put it, “with friends like [Trump], who needs enemies.”

Trump’s trade tactics, aimed at stemming America’s relative economic decline, reflect the same muscular mercantilism that China has used to become rich and powerful. Both countries are now not only actively undermining the rules-based trading system; they seem to be proving that, as long as a country is powerful enough, it can flout shared rules and norms with impunity. In today’s world, it seems, strength respects only strength.

This dynamic can be seen in the way Trump and Xi respond to each other’s unilateralism. When the US deployed its Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system in South Korea, China used its economic leverage to retaliate against South Korea, but not against America.

Likewise, after Trump signed the Taiwan Travel Act, which encourages official visits between the US and the island, China staged war games against Taiwan and bribed the Dominican Republic to break diplomatic ties with the Taiwanese government. The US, however, faced no consequences from China.

As for Trump, while he has pressed China to change its trade policies, he has given Xi a pass on the South China Sea, taking only symbolic steps – such as freedom of navigation operations – against Chinese expansionism. He also stayed silent in March, when Chinese military threats forced Vietnam to halt oil drilling within its own exclusive economic zone. And he chose to remain neutral last summer, when China’s road-building on the disputed Doklam plateau triggered a military standoff with India.

Trump’s “America First” strategy and Xi’s “Chinese dream” are founded on a common premise: that the world’s two biggest powers have complete latitude to act in their own interest. The G2 world order that they are creating is thus hardly an order at all. It is a trap, in which countries are forced to choose between an unpredictable and transactional Trump-led US and an ambitious and predatory China.