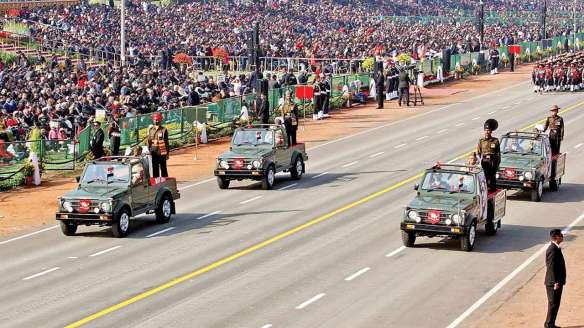

China is left with just one real ally — Pakistan. © Reuters

Beijing’s support protects Islamabad from global pressure to suppress militants

Such appeals have been made by the United States, Japan and European powers but one voice has been conspicuous by its absence — China’s.

If anything, Beijing has sought to shield Pakistan from international censure. Most recently, on March 13, China blocked United Nations Security Council action against the ailing founder of the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed group, which is already under international terrorism sanctions. The aim was not to protect a terrorist leader reportedly on his deathbed but to frustrate the international pressure that has grown on Islamabad to take credible anti-terror actions.

The U.S., for example, has insisted Pakistan take “sustained, irreversible action against terrorist groups.” Jaish-e-Mohammed, which was quick to claim responsibility for the Valentine’s Day attack, is just one of 22 U.N.-designated terrorist entities that Pakistan hosts.

Pakistan’s civilian leadership routinely denies that the country’s military cultivates terrorist surrogates. But India holds Islamabad responsible for multiple outrages including the Valentine’s Day attack, which coincided with deadly terrorist strikes on Iranian and Afghan troops that Tehran and Kabul also blamed on Pakistan.

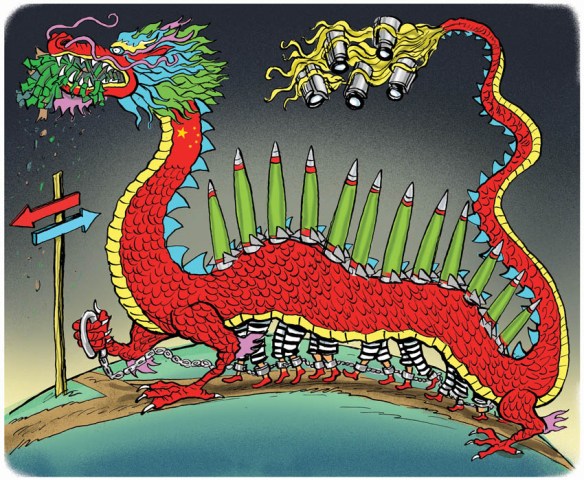

In coming to Pakistan’s help at a critical time, China has highlighted the strategic importance it still attaches to its ties with that increasingly fragile and debt-ridden country. In contrast to America’s strong network of allies and partners, China can count on few true strategic allies or reliable security partners. When it joined hands with Washington to impose new international sanctions on North Korea, once its vassal, Beijing implicitly highlighted that it was left with just one real ally — Pakistan.

The China-Pakistan axis has been cemented by “iron brotherhood,” with the two “as close as lips and teeth,” according to Beijing. It calls Pakistan its “all-weather friend.”

China, however, has little in common with Pakistan, beyond the fact that both are dissatisfied with their existing frontiers and claim territory held by neighbors. Their “iron brotherhood” is actually about a shared interest in containing India. That interest has raised the specter for New Delhi of a two-front war in the event military conflict breaks out with either Pakistan or China.

However, the immediate threat India faces is asymmetric warfare, including China’s “salami slicing” strategy of furtive, incremental territorial encroachments in the Himalayas and Pakistan’s use of terrorist proxies. No surprise then, that China seeks to shield Pakistan’s proxy war by Islamist terror against India. Beijing seems untroubled by the seeming contradiction between this approach abroad while, at home, it locks up more than a million Muslims from Xinjiang in the name of cleansing their minds of extremist thoughts.

For years, China has been attracted by Pakistan’s willingness to serve as its economic and military client. China has sold Pakistan weapons its own military has not inducted, as well as prototype nuclear power reactors.

Since at least 2005, Pakistan has allowed Beijing to station thousands of Chinese troops in the Pakistani part of the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, where control is divided between India (45%), Pakistan (35%) and China (20%). More recently, China has sought to turn Pakistan into its land corridor to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. With Chinese involvement, the northern Arabian Sea is becoming militarized: China has supplied warships to the Pakistani navy, it controls Pakistan’s Gwadar port, and its submarines are on patrol.

For Pakistan, however, China’s close embrace is becoming a tight squeeze financially. Fast-rising debt to Beijing has contributed to Pakistan’s dire financial situation today. With its economy teetering on the brink of default, Pakistan is urgently seeking a $12 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

Pakistan is the largest recipient of Chinese financing under President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative. The Pakistani military has created a special 15,000-troop army division to protect Chinese projects. In addition, thousands of police have been deployed to protect Chinese workers. Yet, underscoring the security costs, attacks on Chinese people in Pakistan have occurred now and then.

Rising financial costs, however, are triggering a pushback against Chinese projects even in friendly Pakistan. The new military-backed Pakistani government that took office last summer under Imran Khan has sought to scrap, scale back or renegotiate some Chinese projects. It downsized the main Chinese railway project by $2 billion, removed a $14 billion dam from Chinese financing, and canceled a 1,320-megawatt coal-based power plant.

China’s predatory practices have come under increasing scrutiny. For example, in return for building Gwadar port, China is receiving, tax-free, 91% of revenues from the port until its return to Pakistan in four decades.

Rising capital equipment imports from China, coupled with high returns for Beijing on its investment, have led to large foreign-exchange outflows, spurring Pakistan’s serious balance-of-payments crisis. Pakistan, seeking new loans to repay old ones, finds itself trapped in a vicious circle.

Yet Pakistan is unlikely to stop being China’s loyal client. Despite Western concern that the tide of Chinese strategic projects is making the country dangerously dependent on China, the relationship brings major benefits for Pakistan, including internationally well-documented covert nuclear and missile assistance from Beijing.

China also provides security assurances and political protection, especially diplomatic cover at the U.N., as has been illustrated by its torpedoing of the U.S.-French-British move to designate the Jaish-e-Mohammed chief as a global terrorist. Western powers failed to persuade China that the threat it cites from Islamist terrorism in its own western region demands that it join hands with them.

However, despite securing billions of dollars in recent emergency loans from China, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan cannot do without a large IMF bailout. This will be Pakistan’s 22nd IMF bailout in six decades, and the largest ever. Pakistan’s cycle of dependency on the IMF has paralleled the rise of its military-Islamist complex.

Unless the latest IMF bailout is made contingent upon concrete anti-terror action, it will, as past experience shows, help underpin Pakistan’s collusion with terrorist groups. This is especially so because a new IMF bailout will also support the Sino-Pakistan link, including by freeing up other resources in Pakistan for debt repayments to Beijing.

Democratic powers, especially the U.S., which holds a dominant 17.46% voting share in the IMF, must now insist on setting tough conditions, including making Pakistan take credible, verifiable and irreversible steps against the terrorist groups that its military has long nurtured. Among other things, an honorable U.S. exit from Afghanistan hinges on the success of such treatment.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including “Water: Asia’s New Battleground,” which won the Bernard Schwartz Award.

Pakistan didn’t wait long to squash India’s Balakot airstrike bravado with its own air incursions. However, the financially strapped country cannot afford a serious escalation of hostilities, not least because India could wreak massive punishment. This explains why Pakistan’s military is at pains to affirm that it is not seeking war.

Pakistan didn’t wait long to squash India’s Balakot airstrike bravado with its own air incursions. However, the financially strapped country cannot afford a serious escalation of hostilities, not least because India could wreak massive punishment. This explains why Pakistan’s military is at pains to affirm that it is not seeking war.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan and removed the Taliban from power, thereby eliminating a key nexus of international terrorism. But now, a war-weary US, with a president seeking to cut and run, has reached a tentative deal largely on the Taliban’s terms. The extremist militia that once harbored al-Qaeda and now carries out the world’s deadliest terrorist attacks has secured not just the promise of a US military

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan and removed the Taliban from power, thereby eliminating a key nexus of international terrorism. But now, a war-weary US, with a president seeking to cut and run, has reached a tentative deal largely on the Taliban’s terms. The extremist militia that once harbored al-Qaeda and now carries out the world’s deadliest terrorist attacks has secured not just the promise of a US military

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/RHTN2OGVHBH7XDD6BSRYFN3LHA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/5RQFIFD4T5CM5HG4HGORADCYLU.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.