It is easy to get caught up in escalating strategic competition and conflict on Earth. But, 50 years after the Apollo 11 mission reached the Moon, guaranteeing the freedom to navigate the stars has become no less essential to global peace and security than safeguarding the freedom to navigate the seas.

BRAHMA CHELLANEY, Project Syndicate

Fifty years after astronauts first walked on the Moon, space wars have gone from Hollywood fantasy to looming threat. Not content with possessing enough nuclear weapons to wipe out all life on Earth many times over, major powers are rapidly militarizing space. Given the world’s increasing reliance on space-based assets, the risks are enormous.

As with the Cold War-era Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union, the new global space race has an important symbolic dimension. And, given the lunar landing’s role in establishing US dominance in space, the Moon is a natural starting point for many of the countries now jostling for position there.

In January, China became the first country to land an unmanned robotic spacecraft on the far side of the Moon. India – which in 2014 became the first Asian country to reach Mars, three years after China’s own failed attempt to leave Earth’s orbit – is scheduled to launch an unmanned mission to the Moon’s uncharted south pole on July 22, a week after the first planned launch was called off at the last minute due to a helium fuel leak. Japan and even smaller countries like South Korea and Israel are also pursuing lunar missions.

But the US will not surrender its position easily. US President Donald Trump’s administration has vowed to “return American astronauts to the Moon within the next five years.” As US Vice President Mike Pence put it, “just as the United States was the first nation to reach the Moon in the 20th century,” it will be the first “to return astronauts to the Moon in the 21st century.”

This escalating space race is not just about bragging rights; countries are also making rapid progress on developing their military space capabilities. Some, like systems that can shoot down incoming ballistic missiles, are defensive. But others, such as anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons technologies that can target space assets, are offensive.

The ability to take advantage of such systems, while denying them to adversaries, is becoming central to military strategies. That is why Trump directed the US Department of Defense to establish the Space Force, an independent military branch that will undertake space-related missions and operations.

The US hopes that such a force can protect its “margin of dominance” in space. Before Patrick M. Shanahan resigned as acting defense secretary last month, he said that that margin is “quickly shrinking,” as newer powers become adept at militarizing commercial space technologies, including those first developed as part of civilian prestige projects. The most notable such powers are Russia and China.

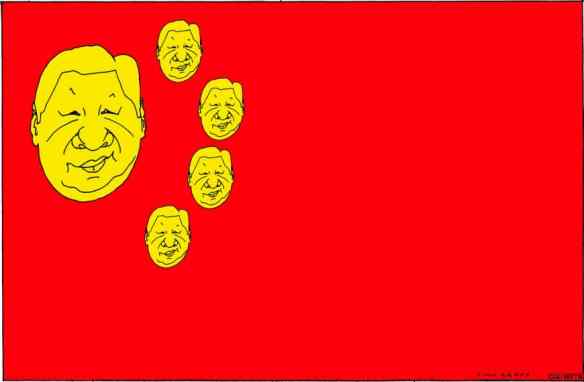

China, which established an independent space force in 2016, is aiming for global leadership in space. And both China and Russia have demonstrated offensive space capabilities in the form of “experimental” satellites that can potentially aid military operations. According to a US Air Force report, the purpose of these countries’ orbiting offensive capabilities is to hold US space assets hostage in the event of conflict.

This highlights the tremendous vulnerability of these assets, and not just those belonging to the US. The existing space infrastructure comprises at least 1,880 satellites owned or operated by 45 countries. These assets support a wide range of activities, including telecommunications, navigation, financial-transaction authentication, connectivity, remote sensing, and weather forecasting. From a security perspective, they facilitate intelligence, surveillance, early warning, arms-control verification, and missile guidance, for example.

There is one more key player in this intensifying space race: India. In March, the country used a ballistic-missile interceptor to destroy one of its own satellites orbiting at nearly 30,000 kilometers (18,641 miles) per hour, making it the fourth power – after the US, Russia, and China – to shoot down an object in space. The test employed some of the same technologies the US used to shoot down an intercontinental ballistic missile in a test conducted just a couple of days before.

Unlike China’s 2007 demonstration of its ASAT capabilities – which left more than 3,000 pieces of debris in orbit – the Indian test faced no international criticism, largely because it was intended to blunt China’s edge in space-war capabilities. In fact, the head of US Strategic Command, General John E. Hyten, defended India’s test: Indians are “concerned about threats to their nation from space,” he said, and thus “feel they have to have a capability to defend themselves in space.”

This sounds a lot like the justification used to build today’s enormous nuclear arsenals, and we know where that logic leads. As with nuclear deterrence, countries continue to upgrade their offensive space capabilities, until “mutually assured destruction” becomes their best hope of protecting themselves and their assets.

Before that happens, international norms and laws must be strengthened. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty bans space-based weapons of mass destruction, but not other types of weapons or ASAT tests. A new treaty is needed to outlaw all use of force in space, with clearly delineated – and reliably enforced – consequences for violations. Likewise, norms for responsible behavior in space must be established, in order to deter ASAT weapons testing or other actions that endanger space assets.

It is easy to get caught up in the escalating strategic competition and conflict on Earth. Safeguarding, say, freedom of maritime navigation in places like the Persian Gulf and the South China Sea (where China continues to shift the territorial status quo unilaterally) is vitally important. But guaranteeing the freedom to navigate the stars has become no less essential to global peace and security.

The F-16 downing issue has not only detracted from Balakot’s main message but also obscured the absence of Indian retribution for the Pakistani blitz. The IAF is sure its MiG-21 shot down an attacking F-16. What is remarkable is that a short, sketchy April 4 US

The F-16 downing issue has not only detracted from Balakot’s main message but also obscured the absence of Indian retribution for the Pakistani blitz. The IAF is sure its MiG-21 shot down an attacking F-16. What is remarkable is that a short, sketchy April 4 US

The irony is that while China justifies its “

The irony is that while China justifies its “

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including “Water: Asia’s New Battleground,” which won the Bernard Schwartz Award.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including “Water: Asia’s New Battleground,” which won the Bernard Schwartz Award.

You must be logged in to post a comment.