Brahma Chellaney, Nikkei Asian Review

Just as the Philippines hauled China before an international arbitral tribunal in The Hague over Beijing’s expansive claims in the South China Sea, Pakistan recently announced its intent to drag India before a similar, specially constituted tribunal in the Dutch city. Pakistan is citing a dispute over the sharing of the waters of the six-river Indus system with India. This is not the first time Pakistan is seeking to initiate such proceedings against its neighbor; nor is it likely to be the last. But it is among the more contentious moves in a long and fraught relationship over water resources. Indeed, seeking international intercession is part of Pakistan’s “water war” strategy against India.

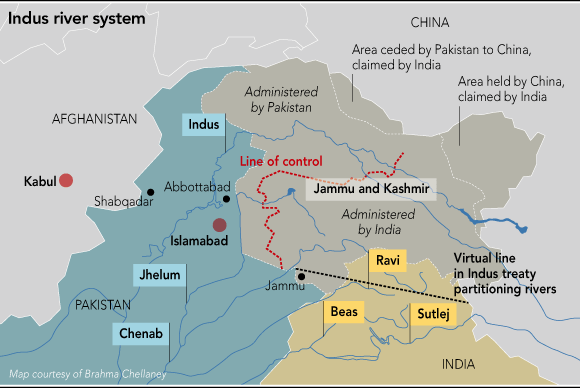

When Pakistan was carved out of India in 1947 as the first Islamic republic of the postcolonial era, the partition left the Indus headwaters on the Indian side of the border but the river basin’s larger segment in the newly-created country. This division armed India with formidable water leverage over Pakistan. Yet, after protracted negotiations, India agreed to what still ranks as the world’s most generous water-sharing pact: The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty reserved for Pakistan the largest three rivers that make up more than four-fifths of the total Indus-system waters.

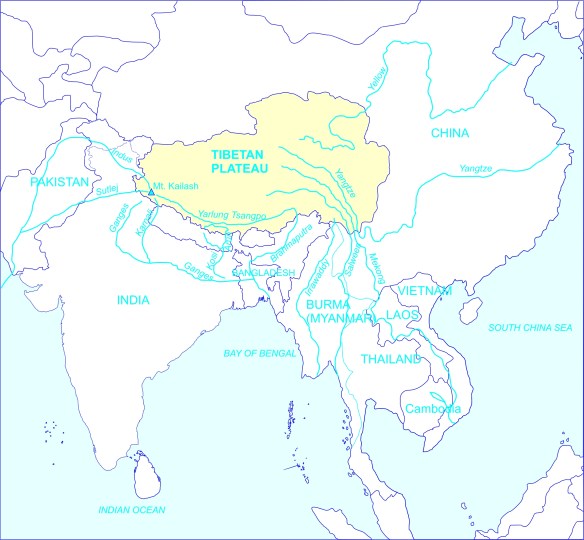

The treaty, which kept for India just 19.48% of the total waters, is the only inter-country water agreement embodying the doctrine of restricted sovereignty, which compels the upstream nation to forego major uses of a river system for the benefit of the downstream state. By contrast, China, which enjoys unparalleled dominance over cross-border river flows because of its control over the water-rich Tibetan Plateau, has publicly asserted absolute territorial sovereignty over upstream river waters, regardless of the downstream impacts. It thus has not signed a water-sharing treaty with any of its 13 downstream neighbors.

A 2011 report prepared for the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee called the Indus pact “the world’s most successful water treaty” for having withstood wars between India and Pakistan in the decades since it was signed. A more important reason why the pact stands out as the titan among existing international treaties is the unmatched scale of the waters it reserves for the downstream state — over 167 billion cu. meters per year. In comparison, the water allocations in the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty are a mere 85 million cu. meters yearly, while Mexico’s share under a 1944 water pact with the U.S. is 1.85 billion cu. meters — 90 times less than Pakistan’s Indus share.

Lack of trust

This background raises two key questions: Why did India leave the bulk of the Indus waters for Pakistan? And why is Pakistan still feuding with India over water? The answers to these questions reveal that when there is a lack of mutual political trust, even a comprehensive water treaty is likely to prove inadequate.

In 1960, at a time of escalating border tensions with China, India sought to trade water for peace with Pakistan by signing the treaty. But the treaty, paradoxically, ended up whetting Pakistan’s desire to gain control of the land — the Indian-administered region of Jammu and Kashmir — through which flowed the three rivers reserved for Pakistani use. With water security becoming synonymous with territorial control in its calculus, Pakistan initiated a surprise war in 1965 to capture Indian Jammu and Kashmir but failed in its mission. (Earlier, in 1948, Pakistan occupied one-third of Jammu and Kashmir and, subsequently, China grabbed one-fifth of the area.)

Over the decades, the disputed Jammu and Kashmir has remained the hub of Pakistan-India tensions. Moreover, the gifting of the river waters of the Indian part of the region to Pakistan by treaty has hampered development there and fostered popular grievance — a situation compounded by a Pakistan-abetted Islamist insurrection. There have been repeated calls in the elected legislature of Indian Jammu and Kashmir for revision or abrogation of the Indus treaty.

India’s belated moves to address the problem of electricity shortages and underdevelopment in its restive part of Jammu and Kashmir by building modestly sized, run-of-river hydropower plants (which use a river’s natural flow energy and elevation drop to produce electricity, without the need for a dam reservoir) have whipped up water nationalism in Pakistan. The treaty, while forbidding India from materially altering transboundary flows, actually permits such projects in India on the Pakistan-earmarked rivers.

In keeping with a principle of customary international water law, the treaty requires India to provide Pakistan with prior notification, including design information, of any new project. Although prior notification does not imply that a project needs the other party’s prior consent, Pakistan has construed the condition as arming it with a veto power over Indian works. It has objected to virtually every Indian project. Its obstruction has delayed Indian projects for years, driving up their costs substantially. Critics see this as part of Pakistan’s strategy to keep unrest in Indian Jammu and Kashmir simmering.

Significantly, the total installed hydropower-generating capacity in operation or under construction in Indian Jammu and Kashmir does not equal the size of a single mega-dam that Pakistan is currently pursuing, such as the 7,000-megawatt Bunji Dam or the 4,500-megawatt Bhasha Dam. Indeed, while railing against India’s run-of-river projects, Pakistan has invited China to build mega-dams in the Pakistani part of Jammu and Kashmir, itself troubled by discontent, including against the growing Chinese footprint there.

History of disputes

Pakistan’s latest decision to seek international arbitration over two Indian projects has followed two other cases in the past decade where it triggered international intervention by invoking the treaty’s conflict-resolution provisions and yet failed to block the Indian works. Treaty provisions permit the establishment of a seven-member arbitral tribunal to resolve a dispute, or the appointment of a neutral expert to settle a disagreement over a hydro-engineering issue. When Pakistan’s minister for defense, water and power, Khawaja Asif, announced on Twitter recently that his country has decided to seek a “full court of arbitration,” most of whose members would be appointed by the World Bank, India contended the move was premature as the treaty-sanctioned bilateral mechanisms had not been utilized first.

Make no mistake: Pakistan, by repeatedly invoking the conflict-resolution provisions to mount political pressure on India, risks undermining a unique treaty. Waging water war by such means carries the danger of a boomerang effect.

Any water treaty’s comparative benefits and burdens should be such that the advantages for each party outweigh the duties and responsibilities, or else the state that sees itself as the loser may fail to comply with its obligations or withdraw from the pact. If India begins to see itself as the loser, viewing the treaty as an albatross around its neck, nothing can save the pact. No international arbitration can address this risk.

When China trashed the recent tribunal ruling that knocked the bottom out of its expansive claims in the South China Sea, it highlighted a much-ignored fact: Major powers rarely accept international arbitration or comply with tribunal rulings. Indeed, arbitration awards often go in favor of smaller states, as India’s own experience shows. For example, an arbitral tribunal in 2014 awarded Bangladesh more than three-quarters of the 25,602 sq. km disputed territory in the Bay of Bengal, even as it left a sizable “gray zone” while delimiting its maritime boundaries with India. Still, India readily accepted the ruling. However, nothing can stop India in the future from emulating the example of, say, China.

To be sure, Pakistan and India face difficult choices on water that demand greater bilateral water cooperation. The Indus treaty was signed in an era when water scarcity was relatively unknown in much of the Indian subcontinent. But today water stress is increasingly haunting the region. In the years ahead, climate change could exacerbate the regional water situation, although currently the glaciers in the western Himalayas — the source of the Indus rivers — are stable and could indeed be growing, in contrast to the accelerated glacial thaw in the eastern Himalayas.

A balance between rights and obligations is at the heart of how to achieve harmonious, rules-based cooperation between co-riparian states. In the Indus basin, however, there is little harmony or collaboration: Pakistan wages a constant propaganda campaign against India’s water hegemony and seeks to “internationalize” every dispute. Yet, in New Delhi’s view, Pakistan wants rights without responsibilities by expecting eternal Indian water munificence, even as its military generals export terrorists to India.

This rancor holds a broader lesson: Festering territorial and other political disputes make meaningful inter-country cooperation on a shared river system difficult, even when a robust treaty is in place.

Brahma Chellaney is the author of “Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis” and “Water: Asia’s New Battleground,” which won the Bernard Schwartz Award.

Water sharing, transparency and collaboration are the pillars on which the unique Indus Waters Treaty was erected in 1960. Islamabad’s recently unveiled intent to haul India again before an international arbitral tribunal is a testament to how water remains a source of discord for Pakistan despite a treaty that is a colossus among existing water-sharing pacts in the world.

Water sharing, transparency and collaboration are the pillars on which the unique Indus Waters Treaty was erected in 1960. Islamabad’s recently unveiled intent to haul India again before an international arbitral tribunal is a testament to how water remains a source of discord for Pakistan despite a treaty that is a colossus among existing water-sharing pacts in the world.

On the Mekong river system — Southeast Asia’s lifeblood — China is building or planning a further 14 dams after completing six. It is also constructing a separate cascade of dams on the last two of its free-flowing rivers — the Salween (which flows into Myanmar and along the Thai border before entering into the Andaman Sea) and the Yarlung Tsangpo, also known as the Brahmaputra, which is the lifeline of northeastern India and much of Bangladesh.

On the Mekong river system — Southeast Asia’s lifeblood — China is building or planning a further 14 dams after completing six. It is also constructing a separate cascade of dams on the last two of its free-flowing rivers — the Salween (which flows into Myanmar and along the Thai border before entering into the Andaman Sea) and the Yarlung Tsangpo, also known as the Brahmaputra, which is the lifeline of northeastern India and much of Bangladesh.

Nearly

Nearly  One of the world’s most bio-diverse but ecologically fragile regions, the Tibetan Plateau is now warming at more than

One of the world’s most bio-diverse but ecologically fragile regions, the Tibetan Plateau is now warming at more than

You must be logged in to post a comment.