By BRAHMA CHELLANEY, Mail Today

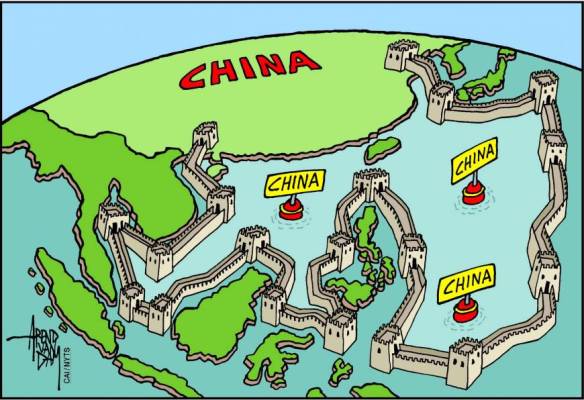

China’s cutting off the flow of a Brahmaputra tributary is just the latest example of its emergence as the upstream water controller through a globally unparalleled hydro-engineering infrastructure centred on dams.

China’s cutting off the flow of a Brahmaputra tributary is just the latest example of its emergence as the upstream water controller through a globally unparalleled hydro-engineering infrastructure centred on dams.

Earlier this year, Beijing itself highlighted its water hegemony over downstream countries by releasing some of its dammed water for drought-hit nations in the lower Mekong basin.

Blocking the flow of the Xiabu river, a Brahmaputra tributary, through a dam project is a significant development, a forewarning that China intends to do a lot more to re-engineer flows in the Brahmaputra system by riding roughshod over the interests of the lower riparians, India and Bangladesh.

Just as it has heavily dammed the Mekong, China is now working to complete a cascade of dams in the Brahmaputra basin.

Dependence

On the Mekong, China has erected six giant dams, with the smallest of them bigger than the largest dam India has built since Independence.

For the downriver countries in that basin, the release of water from the Chinese dams to combat drought was a jarring reminder of not just China’s new-found power to control the flow of a life-sustaining resource, but also of their own reliance on Beijing’s goodwill and charity.

With a further 14 dams being built or planned by China, their dependence on Chinese goodwill is likely to deepen – at some cost to their strategic leeway and environmental security.

Armed with such leverage, Beijing is pushing its Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) initiative as an alternative to the lower-basin states’ Mekong River Commission, which China has spurned over the years.

Indeed, having its cake and eating it, China is a dialogue partner but not a member of the Mekong River Commission, underscoring its intent to stay clued in on the discussions, without having to take on any legal obligations.

The Mekong, Southeast Asia’s lifeline, is just one of the international rivers China has dammed.

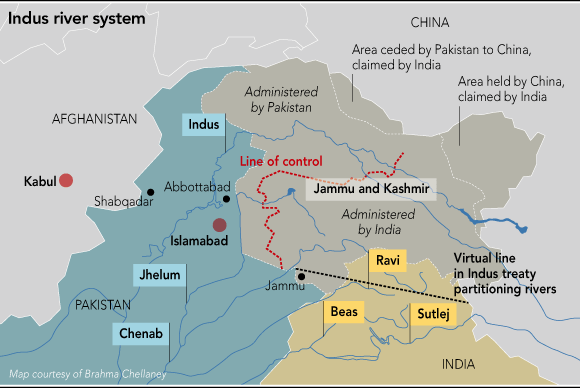

It has also targeted the Arun, the Indus, the Sutlej, the Irtysh, the Illy, the Amur and the Salween, besides the Brahmaputra.

These rivers flow into India, Nepal, Kazakhstan, Russia or Myanmar.

Asia’s water map changed fundamentally after the communists took power in China in 1949.

It wasn’t geography but guns that established China’s chokehold on almost every major transnational river system in Asia, the world’s largest and most-populous continent.

Absorption

By forcibly absorbing the Tibetan Plateau (the giant incubator of Asia’s main river systems) and Xinjiang (the starting point of the Irtysh and the Illy), China became the source of trans-boundary river flows to the largest number of countries in the world, extending from the Indochina Peninsula and South Asia to Kazakhstan and Russia.

Beijing’s claim over these sprawling territories, which make up more than half of China’s landmass today, drew from the fact that they were imperial spoils of the earlier foreign rule in China.

Before the communists seized power, China had only 22 dams of any significant size. But now, China boasts more large dams on its territory than the rest of the world combined.

If dams of all sizes and types are counted, their number in China surpasses 85,000. Strongman Mao Zedong initiated an ambitious dam-building programme, but the majority of the existing dams were built in the period after him.

China’s dam frenzy, however, shows no sign of slowing. The country’s dam builders, in fact, are shifting their focus from the dam-saturated internal rivers (some of which, like the Yellow, are dying) to the international rivers, especially those that originate on the waterrich Tibetan Plateau.

This raises fears that the degradation haunting China’s internal rivers could be replicated in the international rivers.

Leverage

China, after all, has graduated to erecting mega-dams.

Take its latest dams on the Mekong: the 4,200- megawatt Xiaowan (taller than the Eiffel Tower in Paris) and the 5,850- megawatt Nuozhadu, with a 190-square-kilometre reservoir.

Either of them is larger than the current hydropower-generating capacity of the lower Mekong states combined.

Despite its centrality in Asia’s water map, China has rebuffed the idea of a water-sharing treaty with any neighbour. The concern is thus growing among is downstream neighbours that China is seeking to turn water into a potential political weapon.

After all, by controlling the spigot for much of Asia’s water, China is acquiring major leverage over its neighbours’ behaviour in a continent already reeling under low freshwater availability.

China is clearly not content with being the world’s most dammed country, and the only thing that could temper its dam frenzy is a prolonged economic slowdown at home.

Flattening demand for electricity due to China’s already-slowing economic growth, for example, offers a sliver of hope that the Salween river could be saved from the cascade of hydroelectric mega-dams that Beijing has planned to build on it.

Even so, China’s riparian might will remain unmatched.

India has finally broken out of years of paralytic indecision and inaction on Pakistan’s proxy war by staging a swift, surgical military strike across the Line of Control — a line it did not cross even during the 1999 Kargil War. Although a limited but unprecedented action, in which Indian paratroopers destroyed multiple terrorist launchpads, it will help to dispel the sense of despair that had gripped India over its prolonged failure to respond to serial Pakistan-backed terrorist attacks.

India has finally broken out of years of paralytic indecision and inaction on Pakistan’s proxy war by staging a swift, surgical military strike across the Line of Control — a line it did not cross even during the 1999 Kargil War. Although a limited but unprecedented action, in which Indian paratroopers destroyed multiple terrorist launchpads, it will help to dispel the sense of despair that had gripped India over its prolonged failure to respond to serial Pakistan-backed terrorist attacks.

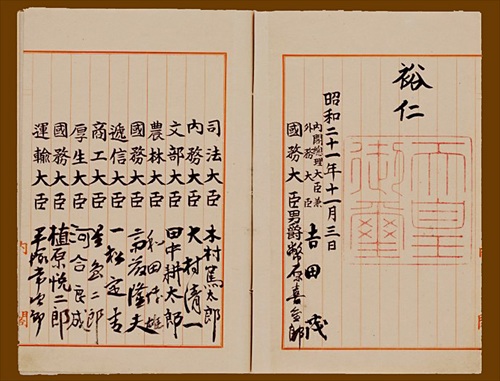

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has secured a rare opportunity for constitutional reform following the July 10 election for the upper house of the Diet, or parliament. His ruling coalition now has a

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has secured a rare opportunity for constitutional reform following the July 10 election for the upper house of the Diet, or parliament. His ruling coalition now has a

You must be logged in to post a comment.