Brahma Chellaney, Project Syndicate

Even after Asia’s economies climb out of the COVID-19 recession, China’s strategy of frenetically building dams and reservoirs on transnational rivers will confront them with a more permanent barrier to long-term economic prosperity: water scarcity. China’s recently unveiled plan to construct a mega-dam on the Yarlung Zangbo river, better known as the Brahmaputra, may be the biggest threat yet.

China dominates Asia’s water map, owing to its annexation of ethnic-minority homelands, such as the water-rich Tibetan Plateau and Xinjiang. China’s territorial aggrandizement in the South China Sea and the Himalayas, where it has targeted even tiny Bhutan, has been accompanied by stealthier efforts to appropriate water resources in transnational river basins – a strategy that hasn’t spared even friendly or pliant neighbors, such as Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Nepal, Kazakhstan, and North Korea. Indeed, China has not hesitated to use its hydro-hegemony against its 18 downstream neighbors.

The consequences have been serious. For example, China’s 11 mega-dams on the Mekong river, Southeast Asia’s arterial waterway, have led to recurrent drought downriver, and turned the Mekong Basin into a security and environmental hot spot. Meanwhile, in largely arid Central Asia, China has diverted waters from the Illy and Irtysh rivers, which originate in China-annexed Xinjiang. Its diversion of water from the Illy threatens to turn Kazakhstan’s Lake Balkhash into another Aral Sea, which has all but dried up in less than four decades.

Against this background, China’s plan to dam the Brahmaputra near its disputed – and heavily militarized – border with India should be no surprise. The Chinese communist publication Huanqiu Shibao, citing an article that appeared in Australia, recently urged India’s government to assess how China could “weaponize” its control over transboundary waters and potentially “choke” the Indian economy. With the Brahmaputra megaproject, China has provided an answer.

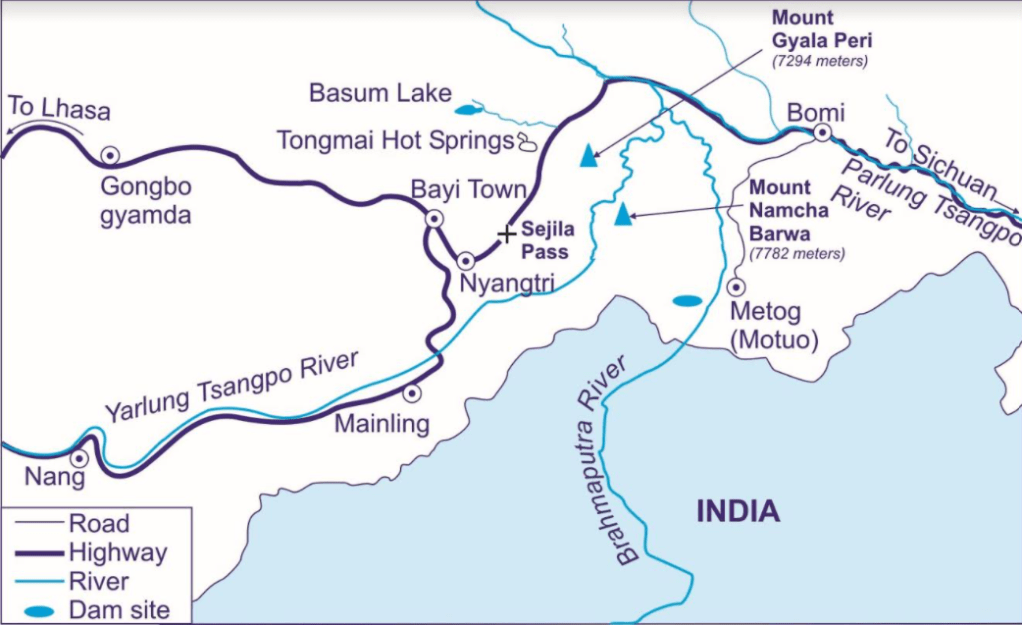

The planned 60-gigawatts project, which will be integrated into China’s next Five-Year Plan starting in January, will reportedly dwarf China’s Three Gorges Dam – currently the world’s largest – on the Yangtze River, generating almost three times as much electricity. China will achieve this by harnessing the power of a 2,800-meter (3,062-yard) drop just before the river crosses into India.

What the chairman of China’s state-run Power Construction Corp, Yan Zhiyong, calls an “historic opportunity” for his country will be devastating for India. Just before crossing into India, the Brahmaputra curves sharply around the Himalayas, forming the world’s longest and steepest canyon – twice as deep as America’s Grand Canyon – and holding Asia’s largest untapped water resources.

Experience suggests that the proposed megaproject threatens those resources – and China’s downstream neighbors. China’s past upstream activities have triggered flash floods in the Indian states of Arunachal and Himachal. More recently, such activity turned the water in the once-pristine Siang – the Brahmaputra’s main artery – dirty and gray as it entered India.

About a dozen small or medium-size Chinese dams are already operational in the Brahmaputra’s upper reaches. But the megaproject in the Brahmaputra Canyon region will enable the country to manipulate transboundary flows far more effectively. Such manipulation could leverage China’s claim to the adjacent Indian state of Arunachal, which is almost three times the size of Taiwan. Given that China and India are already locked in a tense, months-long military standoff, which began with Chinese territorial encroachments, the risks are acute.

And yet the country that will suffer the most as a result of China’s Brahmaputra dam project is not India at all; it is densely populated and China-friendly Bangladesh, for which the Brahmaputra is the single largest freshwater source. Intensifying pressure on its water supply will likely trigger an exodus of refugees to India, already home to millions of illegally settled Bangladeshis.

The Brahmaputra megaproject also amounts to a slap in the face of Tibet, which is among the world’s most biodiverse regions and has a deeply rooted culture of reverence for nature. In fact, the canyon region is sacred territory for Tibetans: its major mountains, cliffs, and caves represent the body of their guardian deity, the goddess Dorje Pagmo, and the Brahmaputra represents her spine.

If none of this deters China, the damage it is doing to its own people and prospects should. China’s over-damming of internal rivers has severely harmed ecosystems, including by causing river fragmentation and disrupting the annual flooding cycle, which helps to refertilize farmland naturally by spreading silt. In August, some 400 million Chinese were put at risk after record flooding endangered the Three Gorges Dam. If the Brahmaputra mega-dam collapses – hardly implausible, given that it will be built in a seismically active area – millions downstream could die.

The Great Himalayan Watershed is home to thousands of glaciers and the source of Asia’s greatest river systems, which are the lifeblood of nearly half the global population. If glacial attrition is allowed to continue – let alone to be accelerated by China’s environmentally catastrophic activities – China will not be spared.

For its own sake – and the sake of Asia as a whole – China must accept institutionalized cooperation on transnational riparian flows, including measures to protect ecologically fragile zones and agreement not to dam relatively free-flowing rivers (which play a critical role in moderating the effects of climate change). This would require China to rein in its dam frenzy, be transparent about its projects, accept multilateral dispute-settlement mechanisms, and negotiate water-sharing treaties with neighbors.

Unfortunately, there is little reason to believe this will happen. On the contrary, as long as the Communist Party of China remains in power, the country will most likely continue to wage stealthy water wars that no one can win.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Asian Juggernaut; Water: Asia’s New Battleground; and Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis.

Ships from the Indian navy, Royal Australian Navy, and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force sail in formation during an exercise as part of Malabar 2020 on Nov. 3. (Handout photo from U.S. Navy)

Ships from the Indian navy, Royal Australian Navy, and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force sail in formation during an exercise as part of Malabar 2020 on Nov. 3. (Handout photo from U.S. Navy)

Tibetan children study at a school in the northern Indian hill town of Dharamsala. © Reuters

Tibetan children study at a school in the northern Indian hill town of Dharamsala. © Reuters Commandos of India’s all-Tibetan Special Frontier Force carry a coffin containing the body of their comrade Tenzin Nyima during his cremation ceremony in Leh on Sept. 7: the funeral’s key message was New Delhi can use Tibet as leverage against Beijing. © Reuters

Commandos of India’s all-Tibetan Special Frontier Force carry a coffin containing the body of their comrade Tenzin Nyima during his cremation ceremony in Leh on Sept. 7: the funeral’s key message was New Delhi can use Tibet as leverage against Beijing. © Reuters

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/HIJC4EGT3FNPFJAL3LNR6YFF2U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/5HK5PB2PIBLMLI5MXWG3YCZD6M.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.