Brahma Chellaney, Project Syndicate

Last time Donald Trump was president, ties between the United States and India flourished. But the bilateral relationship began to fray during Joe Biden’s presidency, owing not least to divisions over the Ukraine war. Will Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s latest meeting with Trump at the White House mark the first step toward restoring this critical relationship?

Trump has made no secret of his conviction that personal bonds between leaders can underpin stronger bilateral relationships. And he and Modi certainly share an affinity: both are nationalist politicians who love little more than to please a roaring crowd with elaborate theatrics. In September 2019, the two came together for a public rally in Houston, attended by 50,000 Indian-Americans and several US legislators. The following February, Trump addressed more than 100,000 people in Ahmedabad. “America loves India,” he declared. “America respects India, and America will always be faithful and loyal friends [sic] to the Indian people.”

US-India relations took a turn for the worse after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The Biden administration mobilized America’s allies and partners to join its campaign to punish Russia – and, ideally, compel it to change its behavior. But far from joining this effort, India stayed neutral and seized the opportunity to secure cheap Russian oil.

There were other points of contention, as well. The Biden administration sought to weaken Myanmar’s military junta by imposing stringent sanctions on the country and sending “non-lethal aid” to rebel groups – a policy that has contributed to instability in India’s border state of Manipur. Biden also coddled Pakistan’s military-backed regime, including by approving a $450 million deal in 2022 to upgrade the country’s fleet of F-16 fighter jets.

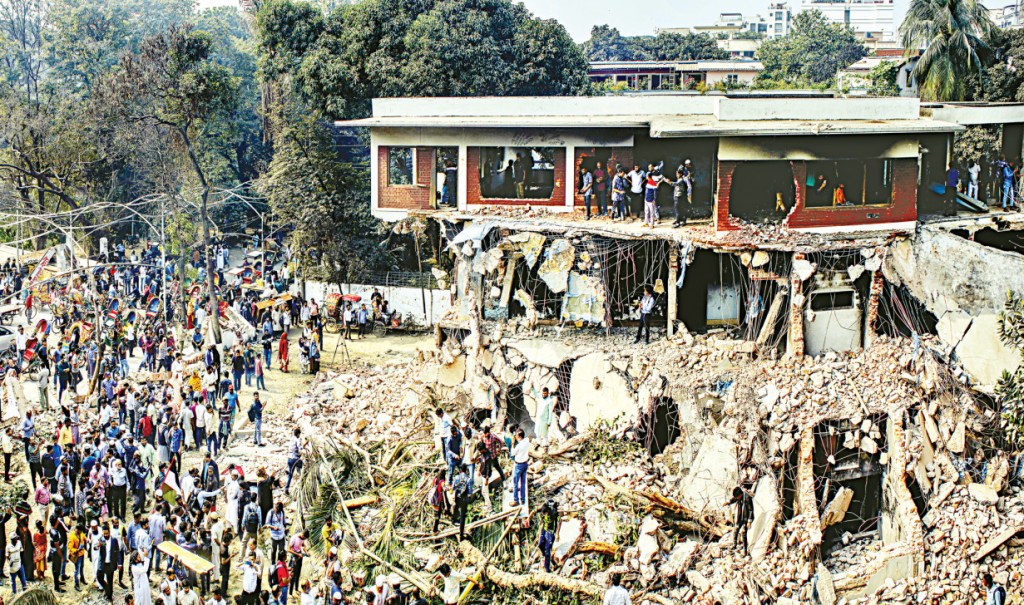

Similarly, Biden welcomed the interim government that Bangladesh’s military installed following the overthrow of the country’s India-friendly government last August. Bangladesh’s rapid descent into lawlessness and Islamist violence since then has raised serious security risks for India, which is already home to millions of illegally settled Bangladeshis.

America’s approach to Sikh separatist leaders on its soil has also raised India’s hackles. Under the Biden administration, the US carried out a criminal investigation into India’s alleged involvement in supposed assassination plots against Sikh militants in the US and Canada. Last September, just days before Biden met with Modi in Delaware, senior White House and US intelligence officials met with Sikh separatists to assure them that they would be protected from “transnational repression.” The following month, the US charged a former Indian intelligence officer in an alleged failed plot to kill a New York-based Sikh militant, who is on India’s most-wanted list.

Against this backdrop, it is easy to see why Trump’s victory in last November’s presidential election raised hopes in India for a reset in bilateral relations. It helps that Trump has repeatedly pledged to negotiate a quick conclusion to the Ukraine war, meaning that India’s choice not to pick a side in that conflict would no longer matter.

A few weeks into Trump’s second presidency, however, there are reasons to doubt this rosy scenario. So far, Trump has done nothing to spare India from his frenetic push to implement his campaign promises, from raising tariffs to deporting undocumented immigrants. When the Trump administration sent more than 100 Indian nationals back to India on a military aircraft – a 40-hour ordeal – their hands and feet were shackled. Modi said nothing.

In fact, far from standing up to Trump, Modi has preemptively slashed tariffs on US imports, hoping that this would keep India out of “Tariff Man’s” sights. But a dissatisfied Trump, who has called India a “very big abuser” of tariffs, has not spared India from his steel and aluminum levies. He wants India to wipe out its $35 billion bilateral trade surplus, by buying more oil and petroleum products, and more weapons, from the US.

India is the world’s third-largest primary energy consumer, after China and the US, and the largest source of oil demand growth. That makes the country a highly attractive market for a US administration that is committed to increasing domestic oil and gas production. It also means that Trump’s commitment to pushing down oil prices, including by applying pressure on OPEC leader Saudi Arabia, would benefit India’s economy.

But Trump has never been particularly concerned about ensuring that his trade agreements are mutually beneficial. Regarding India, his plan may well be to use the threat of tariffs to compel Modi’s government to accept the trade deal of his choosing. That is what he did to Japan during his first presidency. He also tried to do it to India, but failed, so he stripped India of its special trade status instead, prompting India to impose retaliatory tariffs on some US products.

If Trump ends up slapping more tariffs on India, the Indian economy could slow, at least marginally. More broadly, Trump’s “America First” trade agenda – which clashes with Modi’s “Make in India” initiative – threatens to undermine India’s status as the world’s “back office,” providing extensive IT and business services to US companies.

Where trade is concerned, Trump treats friends and foes alike. But it matters that India is a friend – and Trump should want to keep it that way. The US-India strategic partnership helps advance the two countries’ shared interests in the Indo-Pacific region, the world’s emerging economic and geopolitical hub, including strengthening maritime security and supporting a stable balance of power. Already, the two countries are working to deepen military interoperability, and the US has overtaken Russia as India’s leading weapons supplier, as new contracts show.

As Trump and Modi build on their rapport, both should recognize that India is America’s most important partner in countering China’s hegemonic ambitions. It is thus in both countries’ interest to restore and deepen the bilateral relationship, including by strengthening collaboration on critical and emerging technologies, from artificial intelligence to biotechnology. Warm personal relations are an added bonus.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Water: Asia’s New Battleground (Georgetown University Press, 2011), for which he won the 2012 Asia Society Bernard Schwartz Book Award.

.JPG?width=780&fit=cover&gravity=faces&dpr=2&quality=medium&source=nar-cms&format=auto)

You must be logged in to post a comment.