A profound geopolitical reconfiguration is in the making, especially as the erosion in America’s leadership role accelerates.

A profound geopolitical reconfiguration is in the making, especially as the erosion in America’s leadership role accelerates.

Brahma Chellaney | OPEN magazine

The crises, conflicts and wars that are currently raging underscore that we are living in fraught times. Indeed, 2024 could bring greater turbulence that intensely impacts the geopolitical landscape.

The wars that Ukraine and Israel are fighting should not obscure Taiwan’s vulnerability to a Chinese attack. The two wars actually increase the risk of a third. If Chinese President Xi Jinping perceives that China has a window of opportunity to act during the US presidency of Joe Biden, he will likely move on Taiwan.

Between the new war in the Middle East, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s aggressive expansionism from the Himalayas to the South and East China Seas, the global order since the end of World War II appears not only finished; we are seeing the advent of a world without order.

Few, however, are going to mourn the demise of the “rules-based international order”, other than the Western power elites. This order was neither centred on rules nor was it truly international. It was a power-based order that was established by the US with the help of its Western allies. Those states that dared to defy the order were punished by the West, including by slapping sanctions on them and staging regime-change military interventions, as happened in Iraq and Libya.

The US not only largely made the rules on which that order was based; it also seemed to believe itself exempt from key rules and norms, such as those prohibiting interference in other countries’ internal affairs. Its interference extended to military invasions. The “rules-based” order, if anything, underscored that international law is powerful against the powerless, but powerless against the powerful.

The withering away of the “rules-based” order, however, is bringing greater instability in international relations, with 2024 likely to highlight growing global dangers and a changing geopolitical landscape, including a return to great-power rivalries. Amid greater international divisiveness, the North-South and East-West divides are set to widen.

The possibility of sustained conflicts between the long-dominant West and China, Russia and the Islamic world cannot be discounted. The competition between the US and China is already shaping up as the main geopolitical axis of the new era. And new alliances and coalitions are increasingly challenging the West’s hold on international institutions, including the financial architecture.

KEY ELECTIONS THAT COULD RESHAPE OUR WORLD

The outcome of a series of major elections in 2024 would likely reverberate across the world. Countries that are home to more than half the global population will hold elections in 2024. They include eight of the 10 most populous countries in the world—Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia, and the US. Key democracies in the Global South—from South Africa and Mexico to India and Indonesia—will go to polls in 2024.

Taiwan’s vote on January 13 will have an important bearing on cross-strait relations. China-Taiwan relations are already very tense because Beijing has regularised coercive pressure on Taipei. Taiwan, with almost as many people as much-larger Australia, is a technological powerhouse that plays a central role in the international semiconductor business. A Chinese annexation of Taiwan will not only make China a more formidable economic power but also threaten global peace and accelerate the global chip shortage. China could ratchet up pressure on Taiwan if the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate Lai Ching-te wins. Lai is committed to defending Taiwan’s sovereignty.

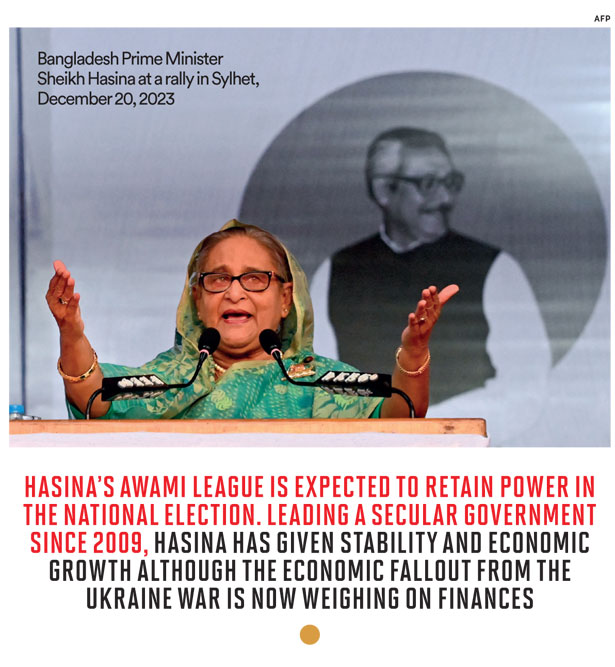

Some of the 2024 elections are unlikely to spring a surprise. In Bangladesh, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League party is expected to retain power in the January 7 national election, especially as the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) is boycotting the polls. Leading a secular government since 2009 that Bangladesh’s Islamists detest, Hasina has given the country political stability and rapid economic growth, although the global economic fallout from the Ukraine war is now weighing on the country’s finances.

The US rightly wants Bangladesh’s election to be free and fair. But ramped-up US pressure on Hasina’s government has had the effect of emboldening opposition activists and Islamists, as the largescale political violence in Dhaka on October 28 showed. Even the residence of the country’s chief justice came under attack. The violence flared when BNP and the country’s largest Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, staged “grand rallies” in the capital to demand that Hasina cede power to a caretaker administration to manage the polls.

The Biden administration has made Bangladesh a focus of its democracy promotion efforts by dangling the threat of visa sanctions against officials who undermine free elections. Yet, at the same time, Washington has condoned the military’s indirect rule in Pakistan, where mass arrests, disappearances and torture have become political weapons. Indeed, Washington has done little to ensure that Pakistan’s forthcoming elections in February would be free and fair.

While continuing to reward Pakistan by prioritising short-term geopolitical considerations, the Biden administration has been criticising democratic backsliding in Bangladesh. In 2021, citing “widespread allegations” of human-rights abuse in the Bangladeshi war on drugs, Washington slapped sanctions on Bangladesh’s elite Rapid Action Battalion and six of its current and former leaders. Bangladesh was excluded from Biden’s Summits for Democracy but military-dominated Pakistan was invited.

Whatever the outcome of Pakistan’s February 8 election, one reality will not change: The country’s domineering military will remain the ultimate hand wielding political power behind a civilian-led government. Pakistan essentially is a one-party state: The only party that has ruled the country directly or indirectly since the first coup in 1958 is the military.

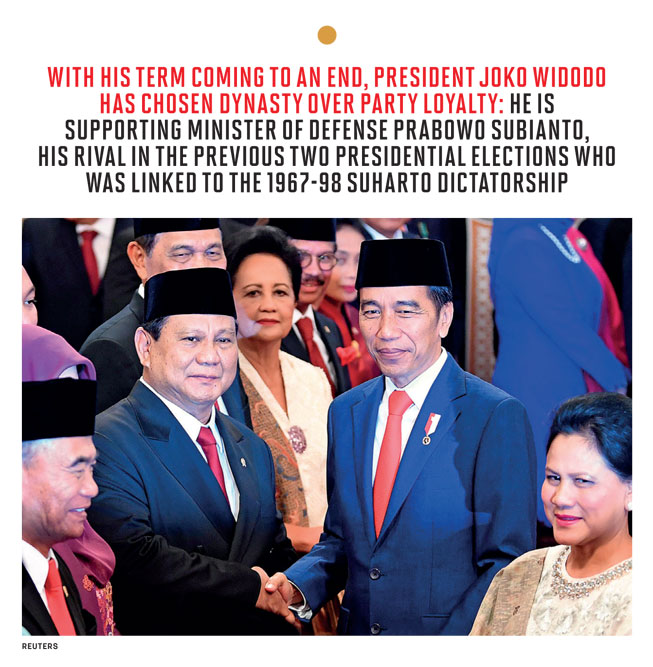

The February 14 general elections in the world’s most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia, are set to help tighten the hold of dynasties on politics. With his term coming to an end, President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo has chosen dynasty over party loyalty: He is supporting not his own party’s presidential candidate but Minister of Defense Prabowo Subianto, his rival in the previous two presidential elections who was linked to the 1967-98 Suharto dictatorship. Indonesia’s Constitution Court, headed by Widodo’s brother-in-law, ruled controversially that Widodo’s son was eligible to run as Prabowo’s running mate, despite not meeting the minimum age requirement of 40 for presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

Turning to Russia, its March 17 presidential election will further cement Vladimir Putin’s grip on power. Under President Putin, Russia is a resurgent power that has been able to ride out unparalleled Western sanctions against it. With the US and its allies deeply involved in the war in Ukraine, even if indirectly, Russia has remade its economy to focus on defence production.

Given his high approval ratings at home, Putin is likely to easily win a fresh term in office, allowing him to pass Soviet leader Joseph Stalin as the longest-serving Russian ruler since Catherine the Great. But, given the West’s gradually escalating proxy war with Russia, the risks of a direct NATO-Russia conflict are growing.

Several countries in Africa with a combined population of more than 340 million, from South Africa and Mozambique to Ghana and Algeria, are scheduled to hold elections in 2024. The general election in South Africa, due between May and August, could possibly spring a surprise, given the corruption scandals and divisions roiling the ruling African National Congress (ANC). ANC risks losing its parliamentary majority for the first time since it took power in 1994. But the fact that the opposition is weak and split could help bail out ANC.

Turning to Europe, there will be multiple parliamentary or presidential elections in 2024 across the continent—from Finland and Belgium to Belarus and Lithuania. The right seems poised to make major gains in several of these elections, especially in Portugal and Austria. An important shift to the right is also likely to emerge from the European Parliament elections from June 6 to 9, which will be the first polls since Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU).

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s term ends in March, yet he has said that it would be “irresponsible” to hold elections while the war is raging. Zelensky (the West’s poster boy for democracy) has banned opposition parties, jailed political opponents, shut down independent media outlets, and clamped down on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church because it is canonically linked to the Moscow Patriarchate. He governs by martial law.

Yet Zelensky is more vulnerable than ever. After the failed Ukrainian counteroffensive against Russia, the long-simmering rift between him and the country’s military leadership has become public, with Zelensky criticising the overall commander of Ukrainian forces, General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, for aptly describing the war as deadlocked. By undermining his political legitimacy through refusal to hold elections, Zelensky is inviting the risk of being ousted by the military. For Zelensky, 2023 was a tough year but 2024 is likely to be even tougher.

Looking at Latin America, Mexico is set to elect its first woman president, with both major political sides fielding women candidates for the June elections. In Venezuela, which is locked in a bitter border feud with Guyana over oil rights, President Nicolás Maduro will seek a fresh term after the US broadly eased sanctions on the country on the back of assurances that the 2024 election would be competitive.

But no 2024 election will have a greater impact on the world than the one in the US on November 5, when voters elect the country’s next president, as well as the entire House of Representatives and a third of the Senate. Biden’s poll numbers are already dismal, even as questions swirl over his mental acuity and physical health. A second term for Biden seems increasingly unlikely. If the weak poll numbers prompt the 81-year-old Biden to drop out of the race, it would not only spark a messy intra-Democratic Party battle over the replacement nominee, but also throw the election into unfamiliar territory.

Biden, like his predecessors, has aggressively promoted democracy in countries that are strategically inconsequential to Washington, such as Myanmar and Bangladesh, while building closer strategic ties with important autocracies, from Saudi Arabia to Vietnam. Such selective promotion of democracy, paradoxically, has come even as more than two-thirds of Americans think US democracy is broken. Indeed, America has been designated by the Stockholm-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) as a “backsliding” democracy.

India’s General Election, for its part, will be critical for the continued upward trajectory of the world’s largest democracy, including its accelerated economic growth, rising international profile and growing clout. India’s economy, the world’s fifth largest, is today the fastest growing among major countries. India has emerged as a powerful voice for the Global South. But without political stability, India cannot hope to sustain its political and economic rise.

More broadly, the elections of 2024 will be spread across all the continents. The outcome of these elections could have a profound impact on our world.

WILL 2024 BE A GLOBE-CHANGING YEAR?

The two raging wars in Ukraine and Gaza, by pitting rival coalitions against each other, have essentially shaped up as great-power conflicts. On one side are the US and its allies that are supporting both Ukraine and Israel, and on the other side are China, Russia, Iran and their partner states.

The two wars actually increase the risk of a Chinese attack on Taiwan. To help contain that danger, Biden is seeking to mend fences with China, as was underlined by his November bilateral summit with Xi in California on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum meeting. Biden’s conciliatory moves have included sending a string of cabinet officials to Beijing and emphasising that the US-led effort is to “de-risk” the relationship with China but not to “decouple” from it.

But with America’s attention focused on Europe and the Middle East, Xi must be observing how Biden’s transfers of artillery munitions, smart bombs, missiles and other weapons to Ukraine and Israel are depleting American stockpiles. Xi would prefer the Ukraine and Israel wars to last as long as possible so that US military stocks are furthered drained and China is better positioned to forcibly incorporate Taiwan.

Make no mistake: Taiwan is on the frontline of international defence against expansionist authoritarianism. The defence of Taiwan must assume greater significance for international security, given that three successive US administrations have failed to credibly push back against China’s expansionism in the South China Sea, whose geopolitical map Beijing has fundamentally altered. Having already swallowed Hong Kong, China may be itching to move on Taiwan, whose incorporation Xi has called a “historic mission”. By rehearsing amphibious and air attacks, China has displayed a willingness to seize Taiwan by force.

Deterring a Chinese attack on Taiwan ought to assume greater priority in US policy. Taiwan cannot be allowed to become the next Ukraine or Hong Kong. Taiwan’s subjugation would significantly advance China’s hegemonic ambitions in Asia and upend the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region, not least by enabling China to break out of the so-called first island chain.

A US that fails to prevent Taiwan’s subjugation would be widely seen as unable or unwilling to defend any other ally, including Japan, which hosts more American troops than any other foreign nation. Such failure, in turn, would likely unravel American alliances in Asia.

Still, Biden places greater emphasis on placating Beijing than on strengthening deterrence, including by taking the possibility of a Chinese blockade of Taiwan seriously. The US needs to urgently bolster Taiwan’s defences by stepping up arms sales and military training. But with Biden continuing to prioritise weapons deliveries to Ukraine, US arms transfers to Taipei are lagging years behind orders.

One illusion in Washington is that the risks of Chinese aggression against Taiwan can be mitigated through regular US-China dialogue, including military-to-military contact. Such thinking misses the fact that China’s strategy centres on stealth, deception and surprise. These three elements have characterised China’s expansionism from the South China Sea to the Himalayas.

Success in the South China Sea, in fact, has made Xi more determined to annex Taiwan on his watch, especially as China erodes America’s military edge in the Indo-Pacific. Worse still, America’s entanglement in the Ukraine war is making Taiwan more vulnerable to Chinese aggression.

Xi could impose war on Taiwan in 2024, knowing that the next American president would be tougher than Biden, who already seems a lame duck president. Biden’s declining health, in fact, symbolises America’s own declining power and influence.

More fundamentally, what is clear is that the world is on the cusp of major geopolitical change, which could also reshape the global financial order as well as investment and energy-trade patterns. Trade and investment flows are already changing in ways that suggest the global economy may split into two major blocs. Growing trade restrictions are one indicator of a de-globalisation trend. Economic fragmentation will hold profound implications for the world economy.

Lest we forget, the US has yet to absorb the lessons of how it undermined its own long-term interests by aiding China’s economic rise over more than four decades. Today, China not only fields the world’s largest navy and coast guard but also is challenging the Western domination of financial and economic organisations. As part of its push for an alternative Sino-led order, China is quietly decoupling large sections of its economy from the West. It now trades more with the Global South than the West.

In modern history, wars, not peace, have helped shape the international order and international institutions. The present US-led global order, including the monetary order as symbolised by the Bretton Woods institutions, emerged from World War II. The United Nations (UN), too, come out from that war. This explains why meaningfully reforming the UN in peacetime has proved problematic.

The UN today appears in irreversible decline, with its role in international affairs marginalised. The hardening gridlock at the UN Security Council, paradoxically, is increasing the role of the structurally weak UN General Assembly, which can make only recommendations as it lacks the power to pass legally binding resolutions on international issues. For example, with the Security Council deadlocked, the General Assembly adopted a resolution on the Gaza war that called for a “humanitarian truce” and an end to Israel’s siege.

The geopolitical churning is happening at a time when the world is at a crossroads, with its future direction uncertain. The challenges we face range from the lack of global leadership and widening inequality and growing authoritarianism across much of the world to the use and misuse of artificial intelligence and the global impacts of environmental degradation and climate change.

More ominously, too often those that cite international law are the ones breaching international law or rules, including the norms against territorial conquest, targeted assassination of foreign officials, and non-intervention and non-interference in other nations’ domestic affairs. The oft-mentioned imperative to uphold a “rules-based order” refers to the rules that even the rule-makers don’t observe when they come in the way of their perceived interests.

Meanwhile, America’s own close allies may be underscoring its waning power and influence. For example, in spite of America being their largest military, political and economic backer, Israel and Ukraine have spurned US advice. US officials have blamed Ukraine’s wide dispersal of forces for its stalled counteroffensive, which has resulted in a deadlocked war with Russia.

Israel rebuffed American counsel to scale back its counterattack and limit the mounting civilian death toll and devastation in Gaza, where the situation—in the words of Philippe Lazzarini, commissioner-general of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East—resembles “hell on Earth”. In its bid to destroy Hamas, Israel has already destroyed vast swathes of the Gaza Strip. By failing to restrain Israel, the US and its Western allies, in the eyes of much of the world’s population, have exposed the hollowness of their commitment to upholding basic human rights.

There may be no direct link between the Ukraine and Gaza wars, yet each is impinging on the other. For example, after the start of hostilities in the Middle East, scepticism about Ukraine aid has increased in the West, with Zelensky acknowledging that the new “conflict takes away the focus” from his country’s war. This is apparent from the stalemate in the US Congress over Biden’s request for $64 billion more in support for Ukraine. Even an EU decision on a $54 billion, multi-year financial assistance package for Ukraine has been delayed. As for the war in Gaza, the longer it continues, the greater will be the risk of a wider Middle East war, which would carry major global impacts just like the war in Ukraine has done.

Even without a wider war, a protracted conflict in Gaza could set in motion a geopolitical reordering in the Greater Middle East, where, with the exceptions of Iran, Egypt, and Turkey, every major power is a modern construct created largely by the British and the French. Israel’s war, for example, is already increasing the geopolitical role of gas-rich Qatar, a regional gadfly that has become an international rogue elephant by funding violent jihadists, including Hamas. Today, Qatar has become central to Israel-Hamas negotiations, including over the hostages.

Other developments, too, portend major shifts in the international order, including the West’s weakening power, Russia’s increasingly militarised economy, China’s stalling growth, and the growing weight of the Global South, where most of the world’s fastest-growing economies are located. Geopolitical risk has never been higher.

In this light, 2024 could be a pivotal year in charting the future direction of our world. The present turbulent times could bring about profound geopolitical reconfiguration, especially as the erosion in America’s leadership role accelerates. The growing weaponisation of trade and the use of sanctions, meanwhile, are undermining the multilateral system.

A new global order, however, is unlikely to emerge anytime soon. What the world is likely to witness is greater instability, including “might makes right” policies.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of two award-winning books: Water, Peace, and War; and Water: Asia’s New Battleground.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, right, and U.S. President Joe Biden in June: Despite an improved relationship, U.S. strategic objectives still diverge from core Indian interests. © Reuters

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, right, and U.S. President Joe Biden in June: Despite an improved relationship, U.S. strategic objectives still diverge from core Indian interests. © Reuters

A banner erected by the Indian army near Pangong Tso lake along the country’s frontier with China. © AP

A banner erected by the Indian army near Pangong Tso lake along the country’s frontier with China. © AP

You must be logged in to post a comment.