Any peace deal should not be about formalising China’s strategic advantages

Brahma Chellaney | OPEN magazine

China and India make up more than one-third of the global population, and enduring enmity between these giants serves neither their national interests nor the cause of Asian stability and security.

The India-China military standoff along the traditional Indo-Tibetan frontier may not be grabbing international headlines, especially with two wars raging elsewhere in the world. But, as External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar said earlier this year, the situation along the border remains “very tense and dangerous”.

Now in its fifth year, the standoff, which has brought potential dark clouds on the horizon, was triggered by furtive Chinese encroachments on some key Ladakh borderlands in April 2020, just before thawing ice normally reopens Himalayan access routes after a brutal winter.

The standoff, however, extends beyond the westernmost Ladakh sector of the border. It encompasses sections of the middle sector, as well as the eastern sector along Tibet’s long border with Arunachal Pradesh. One confrontation location is opposite the narrow, 22km-wide corridor known as “the chicken-neck” that connects India’s Northeast to the rest of the country. The corridor’s vulnerability has been increased by Chinese encroachments on Bhutan’s southwestern borderlands.

While both sides have significantly ramped up deployments of troops and weapons, as if preparing for a possible war, China has frenetically been building new warfare-related infrastructure along the inhospitable frontier. Its focus has been on building underground military facilities that can survive aerial attacks in war. So, it has been boring tunnels and shafts in mountainsides to set up command positions, reinforced troop shelters and weapons-storage facilities.

In addition, China has been systematically planting settlers in new militarised border villages along the India frontier. These artificial villages are becoming the equivalent of the artificial islands Beijing created in the South China Sea to serve as its forward military bases.

China, meanwhile, has stepped up other provocations against India, including Sinicising the names of places in Arunachal Pradesh to help strengthen its territorial claim to that sprawling state, which is almost three times larger in area than Taiwan. Indeed, Beijing has been calling Arunachal Pradesh “South Tibet”, contending it was once part of Tibet—a claim the Dalai Lama says has no historical basis.

Against this backdrop, talks to de-escalate tensions and end the standoff have made little headway after the two sides agreed long ago to turn three specific confrontation sites into buffer zones. The fact that those buffers have come up largely in territories that were within India’s patrolling jurisdiction has underscored China’s negotiating leverage.

Still, it makes strategic sense for both China and India to try and find common ground to defuse their border confrontation. Some signals, even if exploratory, suggest that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s regime may now be seeking to smooth over tensions with India.

As in 1962, when China triggered a war by invading India, the Ladakh encroachments are counterproductive to long-term Chinese interests. The 1962 war shattered Indian illusions about China and set in motion India’s shift away from pacifism. In 1967, while still recovering from the 1962 war and another war with Pakistan in 1965, India gave China a bloody nose in military clashes along the Tibet-Sikkim border.

In terms of territory gained, China’s 2020 Ladakh aggression may have been a success. But, politically, it has proved self-damaging, driving India closer to the US and setting in motion a major Indian military buildup, including in the missile and nuclear realms. Relations between Beijing and New Delhi are at a nadir.

This seems a replay of 1962, when China set out, in the words of then-Premier Zhou Enlai, to “teach India a lesson”. China won that war but lost the peace. The difference now is that, without defusing the border crisis, China risks making a permanent enemy of its largest neighbour.

Even militarily, it does not make sense for China to prolong the standoff at a time when its expansionist strategy is targeting Taiwan and seeking to transform the South China Sea into a “Chinese lake”. Referring to the Indian military’s ongoing confrontation with Chinese forces, Admiral Mike Gilday, the chief of US naval operations, said in August 2022 that India presents China a two-front problem: “They [Indians] now force China to not only look east, toward the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, but they now have to be looking over their shoulder at India.”

President Xi Jinping‘S dilemma is how to resolve the Himalayan military crisis without losing face. The longer the standoff persists, the greater would be the risk for Beijing of turning India into an enduring enemy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, despite taking some flak at home over China’s Ladakh encroachments, has continued to search for a settlement through quiet diplomacy

Today, Xi’s self-made dilemma is how to resolve the Himalayan military crisis without losing face. But the longer the standoff persists, the greater would be the risk for Beijing of turning India into an enduring enemy, a development that could weigh down China’s global and regional ambitions, including Xi’s self-described “historic mission” to absorb Taiwan.

Without the elements of stealth, deception and surprise, which characterised its encroachments, China would be hard put to get the better of the Indian armed forces in a war. While the Chinese military relies heavily on conscripts, India has an all-volunteer force that is considered the world’s most experienced in mountain warfare.

For his part, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, despite taking some flak at home over China’s Ladakh encroachments, has continued to search for a settlement through quiet diplomacy.

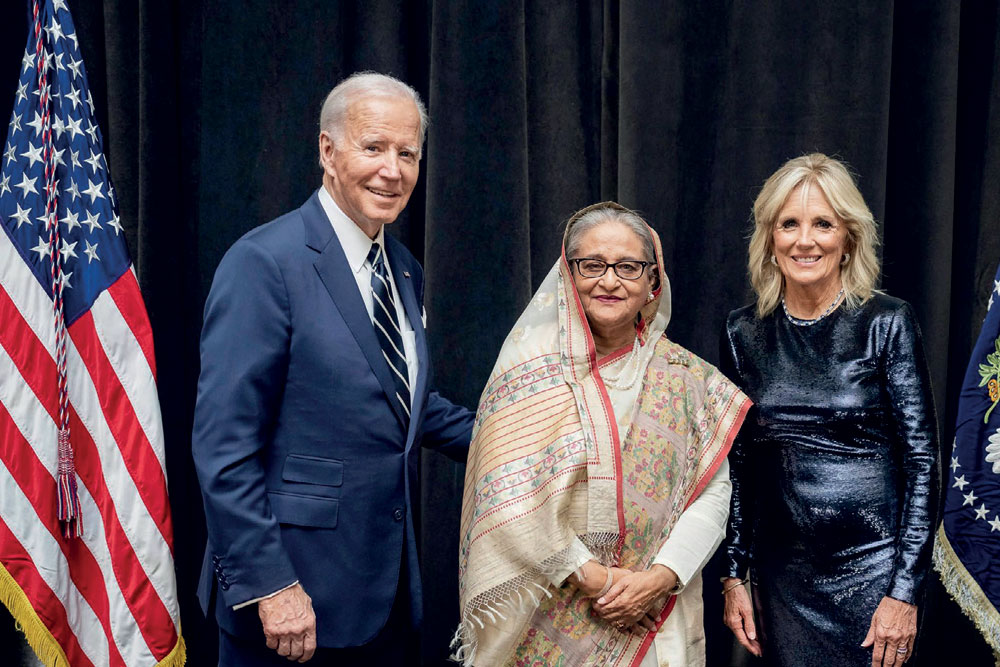

In stark contrast to US President Joe Biden shutting the door to diplomacy with Moscow following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Modi has kept diplomatic space for finding a negotiated end to the border crisis, including by refraining from imposing any tangible sanctions against China. While his government has banned numerous Chinese mobile apps and blocked certain Chinese investments, it has shied away from substantive punitive action.

This has led to a strange paradox: Amid the border confrontation, China’s trade surplus with India has continued to surge. Its trade surplus has already surpassed India’s total defence budget, the world’s third largest.

One incentive for India to mend fences with China is that, despite the military standoff creating room for a US-India strategic nexus, American policies and actions continue to add to India’s regional security challenges. The US and India may agree on some broader strategic issues internationally, but in India’s own neighbourhood extending from Myanmar to the Pakistan-Afghanistan belt, it is becoming clearer that American policies do not align with core Indian interests. Bangladesh is just the latest wake-up call for New Delhi.

Jaishankar said in March that India remains “committed to finding a fair, reasonable” agreement with China. In fact, Modi briefly discussed ways to defuse the border crisis with Xi on the sidelines of multilateral summits in Bali and Johannesburg in November 2022 and August 2023, respectively.

The forthcoming BRICS and G20 summits will offer opportunities for Modi and Xi to meet on the margins, creating an impetus for both sides to work out a possible deal through quiet diplomacy. The BRICS summit (the first after the group’s major expansion) will be held in Kazan, Russia, from October 22 to 24, to be followed by the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on November 18-19.

With Russia taking an active interest in a potential end to the Sino-Indian border confrontation, the BRICS summit (to which Russian President Vladimir Putin has also invited some non-BRICS leaders, including the presidents of Iran and Azerbaijan) could potentially serve as a catalyst for reaching some sort of a ‘peace’ deal between Beijing and New Delhi. This may well explain renewed back-channel discussions, as well as Jaishankar’s meetings with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, who is also a Communist Party of China (CPC) Politburo member.

The BRICS Summit could potentially serve as a catalyst for reaching some sort of a ‘peace’ deal between Beijing and New Delhi. This may well explain renewed back-channel discussions, as well as Jaishankar’s meetings with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi, who is also a CPC politburo member

To be sure, New Delhi has all along been open to patching things up with China. At the same time, it has displayed an unflinching resolve to stand up to China: it has not only matched China’s Himalayan military deployments, but also made clear that the standoff cannot end as long as Beijing continues to violate bilateral border-management agreements and engage in intimidation and coercion.

Xi’s failure, while green-lighting the 2020 encroachments, to anticipate a robust Indian military response openly challenging Chinese power and capability was a serious strategic miscalculation.

Since the standoff began, India has tested several leading-edge missile systems, and recently boosted its nuclear deterrent by commissioning a second nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN). Powered by an 82.5MW pressurised light water reactor (LWR), <INS Arighat> is armed with 12 K-15 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). A third SSBN with the longer-range K-4 SLBMs to deter China is nearing completion.

However, India has done little to build bargaining leverage against China, which is why the buffer zones at Galwan Valley, Pangong Lake and Gogra-Hot Springs were established largely on Indian territories.

India should have responded to the 2020 Chinese encroachments by sending troops into strategic Chinese-held areas in Tibet. This would have raised the costs for Chinese border violations, thereby boosting deterrence.

Ukraine’s recent incursion into Russian territory sought to seize territory that could serve as a bargaining chip in future negotiations. A counter territorial grab has always made strategic and military sense. It is inexplicable why India, in response to the Chinese encroachments, has chosen to stay locked in a military standoff without seeking to gain counter-leverage by seizing some Chinese-held territory in Tibet.

To make matters worse, India even vacated the strategic Kailash Range as part of the 2021 Pangong Lake deal, which, like the buffer zones elsewhere, has worked to China’s military advantage.

In the Pangong region, the entire buffer zone was set up on territory that India had patrolled until China made its stealth encroachments in April 2020. The buffer, in fact, also includes a swath of Indian area that China had never disputed or claimed. This is the area from Finger 4 to the Indian base (between Fingers 2 and 3). All this has encouraged China to construct a division-level headquarters at the edge of the lake, along with two bridges across the lake and underground warfare-related facilities, placing it in an ascendant position in the Pangong region.

More broadly, the standoff persists despite more than four years of military and diplomatic negotiations because China has used those talks to take India round and round the mulberry bush, while it has been quietly consolidating its encroachments and building new warfare-related infrastructure along the entire Indo-Tibetan frontier.

Its frenzied construction has fundamentally changed the Himalayan military landscape. And the three buffer zones it foisted on India have formalised a changed status quo.

Today, there are still no answers to two key questions. First, why was India taken unawares by China’s stealth encroachments of April 2020, whose costs have increased with the passage of time? And second, why did India subsequently, as part of bilateral accords to set up some buffer zones, withdraw from its historically claimed areas in the Galwan, Pangong and Gogra-Hot Springs regions?

If a ‘peace’ deal were to be concluded in whatever shape, a few things will not change, though. With China having forcibly changed the territorial status quo in eastern Ladakh, a return to status quo ante is most unlikely. In January, then Indian Army Chief General Manoj Pande said the standoff would continue until China pulled back from its Ladakh encroachments, calling restoration of the previous frontier line “our first aim to achieve”. That aim is clearly unrealistic.

In the Pangong region, the entire buffer zone was set up on territory that India had patrolled until China made its stealth encroachments in April 2020. The buffer also includes a swath of Indian area that China had never disputed or claimed

Xi risks being hoisted by his own petard if he pulls back his forces from encroached areas. He would face questions at home as to why, in the first place, he embarked on the aggression against India. Indeed, China’s Ladakh encroachments appeared to be part of Xi’s larger strategy to use coercion and territorial grabs to compel neighbouring countries to acquiesce to China’s claims.

Even if a deal to end the standoff materialises, China’s warfare-related infrastructure along the Himalayan frontier will remain in place. Any agreement, even if it seeks to implement a sequential process of disengagement, de-escalation and de-induction of rival forces, will not alter the new military realities that China has created.

As the 2017 Doklam disengagement deal showed, China withdraws only temporarily. Within weeks of the deal, it sent in large numbers of troops and effectively captured the Doklam Plateau.

Let us be clear: It does make eminent sense for China and India, as two of the world’s most ancient civilisations, to find ways to peacefully coexist as neighbours and cooperate on shared objectives. But the CPC’s record since it came to power in 1949 indicates that it operates on very different logic.

New Delhi is still struggling to understand why Xi—despite meeting Modi 18 times over nearly six years and despite the two countries’ commitment to the “Wuhan spirit” and to open “a new era of cooperation” through the “Chennai connect”—betrayed India’s trust by stealthily encroaching on Ladakh borderlands. If Xi wanted peaceful, mutually beneficial cooperation with India, such aggression would have been the last thing on his mind.

In this light, any ‘peace’ deal that China concludes with India will not be about peace but about formalising its strategic advantages.

Even if the Modi government were to try and market such a deal as a political win, India, militarily, would not be able to lower its guard. The Indo-Tibetan frontier is likely to remain a ‘hot’ border, underscoring both the enduring nature of the military threat posed by China and the lasting costs of India’s failure to prevent the 2020 encroachments, which have led to China significantly changing the Himalayan military landscape.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of two award-winning books: Water, Peace, and War; and Water: Asia’s New Battleground.

Police officers stand next to police vehicles outside the hospital where Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico was taken after a shooting incident in Handlova, Slovakia on May 17. © Reuters

Police officers stand next to police vehicles outside the hospital where Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico was taken after a shooting incident in Handlova, Slovakia on May 17. © Reuters

You must be logged in to post a comment.