Brahma Chellaney, Mint

With the horrific Paris attacks refocusing global spotlight on the scourge of international terrorism, we should not forget the factors that continue to aid the rise of jihadist forces. The international fight against transnational Islamic terrorism can never succeed as long as short-term geostrategic interests prompt Western powers to form alliances of convenience that strengthen fundamentalist forces extolling violence as a sanctified tool of religion.

With the horrific Paris attacks refocusing global spotlight on the scourge of international terrorism, we should not forget the factors that continue to aid the rise of jihadist forces. The international fight against transnational Islamic terrorism can never succeed as long as short-term geostrategic interests prompt Western powers to form alliances of convenience that strengthen fundamentalist forces extolling violence as a sanctified tool of religion.

Islamic terrorism poses an existential threat to liberal, pluralistic states everywhere, not just in the West. So, the interventionist policies of some powers that unwittingly bolster Islamist forces threaten not just their internal security but also that of other democracies with sizable Muslim populations.

Make no mistake: The war on terror cannot be credibly fought with treacherous allies, such as jihadist rebels and fundamentalism-exporting sheikhdoms. Indeed, the pursuit of near-term geostrategic goals at the cost of long-term interests has created an energized international jihadist threat and fostered greater transnational terrorism. The focus on securing short-term gains is helping to inflict long-term pain on the international community.

The notion that Western powers can aid “moderate” jihadists in faraway lands — training them in how to make and detonate bombs and arming them with lethal weapons — and yet not endanger their own security has repeatedly been shown to be false. The training and arming of such militants in collaboration with reactionary Islamist sheikhdoms has only allowed these countries’ cloistered royals to play double games and bankroll Muslim extremist groups and madrasas in many countries.

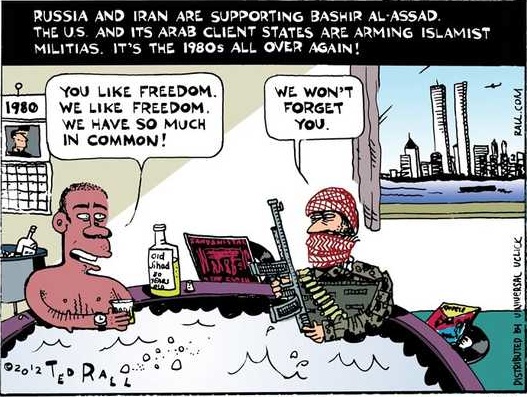

In fact, it is the state and non-state allies of convenience since the 1980s — when the CIA trained and armed thousands of anti-Soviet Afghan rebels with Arab petrodollars and the help of Pakistan’s rogue Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency — that have come to haunt the security of Western and non-Western democracies alike.

In 1985, at a White House ceremony attended by several Afghan top-ranking “mujahedeen” — the jihadists out of which Al Qaeda emerged — President Ronald Reagan gestured toward his guests and declared, “These gentlemen are the moral equivalent of America’s Founding Fathers.” It was the Reagan administration’s use of Islam as an ideological tool to spur jihad against the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan that created Al Qaeda, undermining the security of several regional states.

As secretary of state, Hillary Clinton admitted in a 2010 ABC News interview that, “We trained them, we equipped them, we funded them, including somebody named Osama bin Laden. And then when we finally saw the end of the Soviet Army crossing back out of Afghanistan, we all breathed a sigh of relief and said, okay, fine, we’re out of there. And it didn’t work out so well for us.”

Today, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, has emerged as a new international monster because the lesson from Al Qaeda’s rise has been ignored. This is apparent from President Barack Obama’s recent decision to ramp up U.S. support to Syrian rebels with nearly $100 million in fresh aid. The decision has come despite the vast majority of the CIA-trained “moderate” jihadists having defected with their weapons to ISIS. Now, ISIS wages its terror campaigns largely with Western weapons and with many Western-trained fighters.

France finds itself increasingly in the crosshairs of terrorism in large part because of President François Hollande’s interventionist impulse. A political lightweight who became president by accident in 2012, Hollande has shown himself to be one of the world’s most interventionist leaders, despite being a socialist. Serial interventions have come to define the “Hollande doctrine.”

Under Hollande’s leadership, France has conducted military operations in Ivory Coast, Somalia, Mali, Central African Republic and the Sahel, provided assistance to Syrian rebels as part of a U.S.-led effort to topple President Bashar al-Assad and, more recently, launched airstrikes in Iraq and Syria. When U.S. President Barack Obama considered sending the U.S. military into combat in Syria in 2013, one foreign leader egging him on was Hollande.

Hollande’s happy interventions, especially in the Middle East, have angered radical elements in France’s sizable Arab immigrant community. Hollande was singled out by name by some of those who carried out the November 13 attacks in Paris. Despite several new security measures being implemented after the Charlie Hebdo attack, including a sweeping surveillance law in the supposed cradle of liberty, France has become more vulnerable to terrorist strikes. Hollande now wants the French Constitution amended.

More broadly, almost every Western intervention in the wider Middle East has triggered unforeseen internal and cross-border consequences. Creating a vicious circle of action and reaction, the unintended effects have then prompted another Western intervention in due course to control the fallout.

For example, many of the Arab and other jihadists trained by the CIA in Pakistan, as part of the Reagan administration’s clandestine war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, later returned to their homelands to wage terror campaigns against governments they viewed as tainted by Western influence. Such Al Qaeda-linked militants were linked to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s assassination and to terrorist attacks on several U.S. targets in the Middle East in the 1990s. Large portions of the multibillion-dollar covert U.S. aid for anti-Soviet Islamic guerrillas were siphoned off by the conduit — Pakistan’s ISI — to ignite a bloody insurgency in the Jammu and Kashmir state of India, which bore the brunt of the unintended consequences of the Russian and U.S.-led interventions in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989.

More than a decade after its proxy war drove Soviet forces out of Afghanistan, the U.S. — following the September 11, 2001, terror attacks at home — invaded Afghanistan. Over 14 years later, it is still embroiled in that war.

Take another example: The U.S.-French-British toppling of strongman Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 has turned Libya into a battle-worn wasteland that now serves as a happy hunting ground for ISIS, Al Qaeda and other jihadists. This has opened the door to the flow of arms and militants to other countries, leading to the French military’s antiterrorist operations from Mali to the Sahel.

No state has unravelled faster and become a terrorist haven due to foreign intervention than Libya. Yet the U.S. has endlessly debated the 2012 killing of four Americans in Benghazi, including its ambassador, but sidestepped the Obama-made disaster that Libya represents. Indeed, one of the first acts of the short-lived successor regime that the Western powers installed in Tripoli was to introduce Shariah — Islamic law rooted in the ultra-extreme Wahhabi form of Sunni Islam.

Today, a lawless Libya continues to export jihad and guns across the Sahel and undermine the security of fellow Maghreb countries and Egypt. As a jihadist stronghold, it also poses a potential threat to European security.

Likewise, the operation led by the U.S., France and Britain to overthrow Assad not only contributed to turning the once-peaceful, secular Syria into a jihadist bastion and vast killing field but also enabled ISIS to rise from its base in northern Syria as a powerful, marauding army that has gained control over vast swaths of territory extending to Iraq.

That, in turn, prompted Obama more than 14 months ago to launch an open-ended bombing campaign against ISIS in Syria and Iraq. According to Henry Kissinger, the “destruction of ISIS is more urgent than the overthrow of Bashar Assad, who has already lost over half of the area he once controlled. Making sure that this territory does not become a permanent terrorist haven must have precedence.”

Obama’s ineffectual air war, however, has done little to contain ISIS but prompted Russia to launch its own airstrikes. The bomb-triggered crash of a Russian jetliner over the Sinai Peninsula and the ISIS-linked Paris attacks now threaten to deepen outside powers’ military involvement in Syria and Iraq and thereby set off a fresh circle of action and reaction.

More fundamentally, the toppling of secular despots in Iraq and Libya and the attempt to overthrow a similar autocrat in Syria have paved the way for the rise of violent extremists in the Sunni arc that stretches from the Maghreb-Sahel region of North Africa to the Afghanistan-Pakistan belt. Several largely Sunni countries, including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Somalia and Afghanistan, have become de facto partitioned, while Jordan and Lebanon face a similar spectre of succumbing to Sunni extremist violence.

In fact, the U.S.-French-British campaign to oust Assad — with the support of Wahhabi sheikhdoms like Saudi Arabia and Qatar — began on the wrong foot by seeking to speciously distinguish between “moderate” and “radical” jihadists. Those waging jihad by the gun can never be moderate, which is why many CIA-trained Syrian rebels have joined ISIS.

Western powers must reconsider their regional strategies, which have long depended on allies of convenience ranging from despotic Islamist rulers, as in the Persian Gulf, to Islamist militias of the type that were used to drive out Soviet forces from Afghanistan or to overthrow Gaddafi. By continuing to shower Pakistan with generous aid and lethal arms, the U.S. unwittingly enables Pakistani export of terrorism to India and Afghanistan.

The West’s dubious allies, ranging from Qatar to Pakistan, have made the international terrorism problem worse. How can the international community combat the ISIS ideology when a major Western ally like Saudi Arabia has played an important role in funding the spread of such ideology and Salafi jihadism?

Western powers must shine a light on their past mistakes so that they don’t repeat them. The Western focus ought to be on securing long-term goals rather than on achieving short-term victories through alliances of convenience.

The larger lesson that should not be forgotten is that unless caution is exercised in training and arming Islamic militants in any region, the chickens could come home to roost. Jihad cannot be confined within the borders of a targeted nation, however distant, as Afghanistan, Syria and Libya illustrate. The involvement of French and Belgian nationals in the Paris attacks indicates how difficult it is to geographically contain the spread of the jihad virus.

You must be logged in to post a comment.