A column internationally syndicated by Project Syndicate.

Category Archives: Terrorism

Vladimir Putin’s geopolitical chessboard

BRAHMA CHELLANEY, The Japan Times

U.S.-led sanctions against Moscow are helping to create a more assertive Russia determined to countervail American power. The bipartisan support in the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee for additional sanctions, even as a special counsel investigates alleged collusion between U.S. President Donald Trump’s election campaign and Moscow, suggests that the U.S.-Russia relationship is likely to remain at a ragged low.

Despite the Russian economy suffering under the combined weight of sanctions and a fall in oil prices, Moscow is spreading its geopolitical influence to new regions and pursuing a major rearmament program involving both its nuclear and conventional forces. Today, Russia is the only power willing to directly challenge U.S. interests in the Middle East, Europe, the Caspian Sea basin, Central Asia and now Afghanistan, where America is stuck in the longest war in its history.

Put simply, the U.S.-led Western sanctions since 2014 are acting as a spur to Russia’s geopolitical resurgence.

In keeping with the maxim that countries have no permanent friends or enemies, only permanent interests, Russia has rejiggered its geopolitical strategy to respond to the biting sanctions against it. Russian President Vladimir Putin has significantly expanded the geopolitical chessboard on which Moscow can play against the United States and NATO.

Historically, strongman governments facing domestic challenges have whipped up nationalism by rallying popular support against foreign adversaries. Who better to blame for Russia’s economic travails than the sanctions-imposing U.S. and its allies? Putin’s jaw-droppingly high approval ratings contrast starkly with the deepening unpopularity at home of his U.S. counterpart.

Putin has shown himself to be a very skilled player of geopolitical chess. Despite Russia’s gross domestic product shrinking to below that of Italy, Putin has managed to build significant Russian clout in several regions. The blunders of Western powers in Iraq, Libya and Yemen, of course, have aided Russian designs in the Middle East.

Putin has made Russia the central player in the bloody Syrian conflict, fueled by outside powers. Until Russia launched its own air war in Syria in September 2015, the U.S.-British-French alliance had the upper hand there, aiding supposedly “moderate” jihadist rebels against Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government and staging separate bombing campaigns against the Islamic State terrorist organization. Russia’s direct intervention, without bogging down its military in the Syrian quagmire, has helped turn around Assad’s fortunes and reshaped Moscow’s relationships with Turkey, Israel and Iran.

As part of his multidimensional chess game, Putin is also building Russian leverage in other countries that are the key focus of U.S. attention — from North Korea to Libya. But it is Russia’s warming relationship with the medieval Taliban militia — the U.S. military’s main battlefield foe in Afghanistan — that has stood out.

Russia’s new coziness with the Taliban, of course, does not mean that the enemy of its enemy is necessarily a permanent friend. Putin is opportunistically seeking to use the Taliban as a tool to weigh down the U.S. military in Afghanistan.

Because of the Taliban’s command-and-control base and guerrilla sanctuaries in Pakistan, Moscow has also sought to befriend that country. This imperative has been reinforced by the continued U.S. unwillingness to bomb the Taliban’s command and control in Pakistan.

The revival of the “Great Game” in Afghanistan is just one manifestation of the U.S.-Russian relationship turning more poisonous. Another sign is Moscow’s stepped-up courting of China. The U.S.-led sanctions have compelled Russia to pivot to China. Putin attended the recent “One Belt, One Road” summit in Beijing despite his concern that China is using that project to displace Russia as the dominant influence in Central Asia.

To be clear, Russia’s growing ties with India’s regional adversaries, China and Pakistan, have introduced strains in the traditionally close relations between Moscow and New Delhi. The paradox is that as India has moved strategically closer to the U.S., American policy has propelled Russia to forge closer ties with Beijing and to build new relationships with the Taliban and Pakistan.

The Russia-U.S. equation has a significant bearing on Asian and international security. Trump came into office taking potshots at the Chinese leadership but wanting to be friends with Russia. However, the opposite has happened: America’s relationship with Russia, according to U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, has hit its lowest point in years while Trump has developed a strong personal relationship with China’s top autocrat, Xi Jinping, who welcomes his mercantile, transactional approach to foreign policy.

This pirouette has happened because, in reality, Trump is battling those who, in the 21st century, are unwilling to forgo a Cold War mentality. Washington may be more divided and polarized than ever but, on one issue, there remains strong bipartisanship — Russia phobia. This has come handy to those seeking to inflict death by a thousand cuts on the Trump presidency, including by calculatedly leaking classified information and keeping the spotlight on the alleged Russia scandal in which there is still no shred of evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Moscow.

Against this backdrop, America’s sanctions against Russia are unlikely to go, despite clear evidence that they are fostering increasing Moscow-Beijing closeness by making Russia more dependent on China. The sanctions effectively undercut a central U.S. policy objective since the 1972 “opening” to Beijing by President Richard Nixon — to drive a wedge between China and Russia.

For Putin, the sanctions represent war by other means and a justification for him to make his next moves on the grand chessboard. With U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker determined to slap Moscow with additional sanctions, U.S.-Russian tensions and rivalries will continue to serve as a strategic boon for China even as they roil regional and international security.

Longtime Japan Times contributor Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and author.

The Age of Blowback Terror

BRAHMA CHELLANEY

A column internationally syndicated by Project Syndicate.

World powers have often been known to intervene, overtly and covertly, to overthrow other countries’ governments, install pliant regimes, and then prop up those regimes, even with military action. But, more often than not, what seems like a good idea in the short term often brings about disastrous unintended consequences, with intervention causing countries to dissolve into conflict, and intervening powers emerging as targets of violence. That sequence is starkly apparent today, as countries that have meddled in the Middle East face a surge in terrorist attacks.

Last month, Salman Ramadan Abedi – a 22-year-old British-born son of Libyan immigrants – carried out a suicide bombing at the concert of the American pop star Ariana Grande in Manchester, England. The bombing – the worst terrorist attack in the United Kingdom in more than a decade – can be described only as blowback from the activities of the UK and its allies in Libya, where external intervention has given rise to a battle-worn terrorist haven.

The UK has not just actively aided jihadists in Libya; it encouraged foreign fighters, including British Libyans, to get involved in the NATO-led operation that toppled Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi’s regime in 2011. Among those fighters was Abedi’s father, a longtime member of the al-Qaeda-linked Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, whose functionaries were imprisoned or forced into exile during Qaddafi’s rule. The elder Abedi returned to Libya six years ago to fight alongside a new Western-backed Islamist militia known as the Tripoli Brigade. His son had recently returned from a visit to Libya when he carried out the Manchester Arena attack.

This was not the first time a former “Islamic holy warrior” passed jihadism to his Western-born son. Omar Saddiqui Mateen, who carried out last June’s Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida – the deadliest single-day mass shooting in US history – also drew inspiration from his father, who fought with the US-backed mujahedeen forces that drove the Soviet Union out of Afghanistan in the 1980s.

In fact, the United States’ activities in Afghanistan at that time may be the single biggest source of blowback terrorism today. With the help of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency and Saudi Arabia’s money, the CIA staged what remains the largest covert operation in its history, training and arming thousands of anti-Soviet insurgents. The US also spent $50 million on a “jihad literacy” project to inspire Afghans to fight the Soviet “infidels” and to portray the CIA-trained guerrillas as “holy warriors.”

After the Soviets left, however, many of those holy warriors ended up forming al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and other terrorist groups. Some, such as Osama bin Laden, remained in the Afghanistan-Pakistan belt, turning it into a base for organizing international terrorism, like the September 11, 2001, attacks in the US. Others returned to their home countries – from Egypt to the Philippines – to wage terror campaigns against what they viewed as Western-tainted governments. “We helped to create the problem that we are now fighting,” then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted in 2010.

After the Soviets left, however, many of those holy warriors ended up forming al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and other terrorist groups. Some, such as Osama bin Laden, remained in the Afghanistan-Pakistan belt, turning it into a base for organizing international terrorism, like the September 11, 2001, attacks in the US. Others returned to their home countries – from Egypt to the Philippines – to wage terror campaigns against what they viewed as Western-tainted governments. “We helped to create the problem that we are now fighting,” then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted in 2010.

Yet the US – indeed, the entire West – seems not to have learned its lesson. Clinton herself was instrumental in coaxing a hesitant President Barack Obama to back military action to depose Qaddafi in Libya. As a result, just as President George W. Bush will be remembered for the unraveling of Iraq, one of Obama’s central legacies is the mayhem in Libya.

In Syria, the CIA is again supporting supposedly “moderate” jihadist rebel factions, many of which have links to groups like al-Qaeda. Russia, for its part, has been propping up its client, President Bashar al-Assad – and experiencing blowback of its own, exemplified by the 2015 downing of a Russian airliner over the Sinai Peninsula. Russia has also been seeking to use the Taliban to tie down the US militarily in Afghanistan.

As for Europe, two jihadist citadels – Syria and Libya – now sit on its doorstep, and the blowback from its past interventions, exemplified by terrorist attacks in France, Germany, and the UK, is intensifying. Meanwhile, Bin Laden’s favorite son, Hamza bin Laden, is seeking to revive al-Qaeda’s global network.

Of course, regional powers, too, have had plenty to do with perpetuating the cycle of chaos and conflict in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia may have fallen out with a fellow jihad-bankrolling state, Qatar, but it continues to engage in a brutal proxy war with Iran in Yemen, which has brought that country, like Iraq and Libya, to the brink of state failure.

Moreover, Saudi Arabia has been the chief exporter of intolerant and extremist Wahhabi Islam since the second half of the Cold War. Western powers, which viewed Wahhabism as an antidote to communism and the 1979 Shia “revolution” in Iran, tacitly encouraged it.

Ultimately, Wahhabi fanaticism became the basis of modern Sunni Islamist terror, and Saudi Arabia itself is now threatened by its own creation. Pakistan – another major state sponsor of terrorism – is also seeing its chickens coming home to roost, with a spate of terrorist attacks.

It is high time for a new approach. Recognizing that arming or supporting Islamist radicals anywhere ultimately fuels international terrorism, such alliances of convenience should be avoided. In general, Western powers should resist the temptation to intervene at all. Instead, they should work systematically to discredit what British Prime Minister Theresa May has called “the evil ideology of Islamist extremism.”

On this front, US President Donald Trump has already sent the wrong message. On his first foreign trip, he visited Saudi Arabia, a decadent theocracy where, ironically, he opened the Global Center for Combating Extremist Ideology. As the US and its allies continue to face terrorist blowback, one hopes that Trump comes to his senses, and helps to turn the seemingly interminable War on Terror that Bush launched in 2001 into a battle that can actually be won.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Asian Juggernaut, Water: Asia’s New Battleground, and Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, is the author of nine books, including Asian Juggernaut, Water: Asia’s New Battleground, and Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis.

Money trumps anti-terror task

Donald Trump’s embrace of a country he long excoriated for its role in sponsoring terrorism reflects the fact that Saudi Arabia is a cash cow for American defense, energy and manufacturing companies.

BY BRAHMA CHELLANEY, The Japan Times

Want evidence that money speaks louder than the international imperative to counter a rapidly metastasizing global jihadi threat, as symbolized by the latest attack in Manchester? Look no further than U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent visit to the world’s chief ideological sponsor of jihadism, Saudi Arabia. The trip yielded business and investment deals for the United States valued at up to almost $400 billion, including a contract to sell $109.7 billion worth of arms to a country that Trump previously accused of being complicit in 9/11.

By exporting Wahhabism — the hyper-conservative strain of Islam that has instilled the spirit of martyrdom and become the source of modern Islamist terror — Saudi Arabia is snuffing out the more liberal Islamic traditions in many countries. Indeed, Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi fanaticism is the root from which Islamist terrorist organizations ranging from the Islamic State group (which claimed responsibility for the Manchester concert attack) to al-Qaida draw their ideological sustenance.

The Manchester attack, occurring close on the heels of Trump’s Saudi visit, has cast an unflattering light on his choice of a decadent theocracy for his first presidential visit overseas. The previous four U.S. presidents made their first trips to a neighboring ally — either Mexico or Canada, which are flourishing democracies. But Trump, the businessman, always seeks opportunities to strike deals, as underscored by his 100-day trade deal with the world’s largest autocracy, China.

But Trump is not alone. In thrall to Saudi money, British Prime Minister Theresa May traveled to Riyadh six weeks before Trump on her most controversial visit since taking office. As if to signal that a post-Bexit Britain would increasingly cozy up to rich despotic states, May flew to Saudi Arabia shortly after triggering Article 50, an action that started a two-year countdown for her country’s exit from the European Union. She has also stepped up her courting of China and enthusiastically endorsed Beijing’s “One Belt, One Road” program, which many EU states see as lacking in transparency and social and environmental accountability.

Anglo-American support and weapons have aided Saudi war crimes in Yemen, which is now on the brink of famine. Mass starvation would ensue there if the Saudis execute their threat to attack the city of Hodeida, now the main port for entry of Yemen’s food supplies. Britain alone has sold over £3 billion worth of arms to Riyadh since the cloistered Saudi royals began their bombardment and naval blockade of Yemen more than two years ago. While London is planning to sell more weapon systems, Trump’s arms package for the Saudis includes guided munitions that were held up by his predecessor, Barack Obama.

Salvaging the global war on terror demands a sustained information campaign to discredit the ideology of radical Islam. But as long as Saudi Arabia continues to shield its insidious role in aiding and abetting extremism by doling out multibillion-dollar contracts to key powers like the U.S. and Britain, it will be difficult to bring the war on terror back on track.

Trump exemplifies the challenge. In a speech to leaders from across the Muslim world who had gathered in Saudi Arabia, the “Make America Great Again” campaigner championed “Make Islam Great Again.” After earlier saying “Islam hates us” and calling for a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the U.S., Trump described Islam as “one of the world’s great faiths” and urged “tolerance and respect for each other.”

It was weird, though, that Trump spoke about the growing dangers of Islamic extremism from the stronghold of global jihadism, Saudi Arabia. The new Global Center for Combating Extremist Ideology that he opened in Riyadh promises to stand out as a symbol of U.S. hypocrisy.

The long-standing U.S. alliances with Arab monarchs have persisted despite these royals bankrolling Islamic militant groups and Islamic seminaries in other countries. Trump cannot hope to deliver credible or enduring counterterrorism results without disciplining Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the other oil sheikhdoms that continue to export Islamic radicalism. But he has already discovered that this is no easy task.

For example, the U.S. alliance with Saudi Arabia yields exceptionally huge contracts and investments for the American economy. In short, Saudi Arabia is a cash cow for American defense, energy and manufacturing companies, as the latest mega-deals illustrate.

Against this background, Trump’s embrace of a country that he long excoriated reflects the success of the American “deep state” in taming him. Hyping the threat from Iran, even if it fuels the deep-seated Sunni-Shiite rivalry, helps to bolster U.S. alliances with Arab royals and win lucrative arms contracts.

Ominously, Trump in Saudi Arabia spoke of building a stronger alliance with Sunni countries, with U.S. officials saying the defense arrangements could evolve into an “Arab NATO.” However, the Sunni arc of nations is not only roiled by deep fissures, but also it is the incubator of transnational jihadis who have become a potent threat to secular, democratic states near and far. IS, al-Qaida, the Taliban, Laskar-e-Taiba, Boko Haram and al-Shabaab are all Saudi-inspired Sunni groups that blend hostility toward non-Sunnis and anti-modern romanticism into nihilistic rage.

In this light, Trump’s Sunni-oriented approach could worsen the problems of jihadism and sectarianism, undermining the anti-terror fight.

The murky economic and geopolitical considerations presently at play foreshadow a long and difficult international battle against the forces of terrorism. The key to battling violent Islamism is stemming the spread of the ideology that has fostered “jihad factories.” There can be no success without closing the wellspring of terrorism — Wahhabi fanaticism. But who will have the courage to bell the cat?

A long-standing contributor to The JapanTimes, Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including “Water, Peace, and War” (Rowman & Littlefield).

A win comes with a challenge for India

Brahma Chellaney, DNA

Pakistan is an incorrigibly scofflaw state for whom international law matters little. Still, India was left with no option but to haul Pakistan before the International Court of Justice after a secret Pakistani military court sentenced to death a former Indian naval officer, Kulbhushan Jadhav, for being an Indian “spy”. At a time when there was no hope to save Jadhav, the ICJ interim order has come as a shot in the arm for India diplomatically.

Pakistan is an incorrigibly scofflaw state for whom international law matters little. Still, India was left with no option but to haul Pakistan before the International Court of Justice after a secret Pakistani military court sentenced to death a former Indian naval officer, Kulbhushan Jadhav, for being an Indian “spy”. At a time when there was no hope to save Jadhav, the ICJ interim order has come as a shot in the arm for India diplomatically.

However, Pakistan’s response to the provisional but binding order that it does not accept ICJ’s jurisdiction in national security-related matters underscores India’s challenge in dealing with a country that violates canons of civilized conduct and engages in barbaric acts, as exemplified by the recent beheading of two Indian soldiers. The concept of good-neighbourly relations seems alien to Pakistan. For example, in the Kashmir Valley, the Pakistani military establishment is actively promoting civil resistance after its strategy of inciting an armed insurrection against India has yielded limited results.

For years, India has stoically put up with the Pakistani military’s export of terrorism. Even as Pakistan violates the core terms of the Simla peace treaty, India faithfully adheres to the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT).

Significantly, the ICJ’s welcome interim order has followed a string of setbacks suffered by India between 2013 and 2016 in three separate cases before international arbitral tribunals. One case involved a maritime boundary dispute in the Bay of Bengal, with the tribunal awarding Bangladesh almost four-fifths of the disputed territory.

A second case, instituted by Pakistan, related to the IWT and centred on its challenge to India’s tiny 330-megawatt Kishenganga hydropower plant. The third case was filed by Italy over India’s initiation of criminal proceedings against two Italian marines, who were arrested for killing two unarmed Indian fishermen.

Despite apparent flaws in the decisions of the tribunals in all three cases, India abided by them. The ICJ is a higher judicial organ than any tribunal, yet it lacks any practical mechanism to enforce its rulings. If Pakistan does not abide by the ICJ order, it will expose itself thoroughly as a rogue state.

In a world in which power respects power, the international justice system cannot tame a wayward state like Pakistan. In the final analysis, India has to tame Pakistan on its own. The ICJ interim order should not obscure this harsh reality.

America’s deepening Afghanistan quagmire

Trump needs to break with failed U.S. policies on the Taliban

A damaged U.S. military vehicle is seen at the site of a suicide bomb attack in Kabul on May 3. © Reuters

Brahma Chellaney, Nikkei Asian Review

The proposed dispatch of several thousand more U.S. troops to war-torn Afghanistan by President Donald Trump’s administration begs the question: If more than 100,000 American troops failed between 2010 and 2012 to bring the Afghan Taliban to the negotiating table, why would adding 3,000 to 5,000 soldiers to the current modest U.S. force of 8,400 make a difference?

For nearly 16 years, the U.S. has been stuck in Afghanistan in the longest and most expensive war in its history. It has tried several policies to wind down the war, including a massive military “surge” under Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, to compel the Taliban to sue for peace. Nothing has worked, in large part because the U.S. has continued to fight the war on just one side of the Afghanistan-Pakistan divide and refused to go after the Pakistan-based sanctuaries of the Taliban and its affiliate, the Haqqani network.

As Gen. John Nicholson, the U.S. military commander in Afghanistan, acknowledged earlier this year: “It is very difficult to succeed on the battlefield when your enemy enjoys external support and safe haven.” Worse still, the Taliban is conspicuously missing from the U.S. list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, while the procreator and sponsor of that medieval militia — Pakistan — has been one of the largest recipients of American aid since 2001, when the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan helped remove the Taliban from power.

The mercurial Trump has revealed no doctrine or strategy relating to the Afghan War. But in keeping with his penchant for surprise, Trump picked Afghanistan for the first-ever battlefield use of GBU-43B, a nearly 10-metric-ton bomb known as the “Mother of All Bombs.” The target, however, was not the U.S. military’s main battlefield enemy — the Taliban — but the so-called Islamic State group, or ISIS, which Gen. Nicholson told the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee earlier had been largely contained in Afghanistan through raids and airstrikes.

To be sure, Trump has inherited an Afghanistan situation that went from bad to worse under his predecessor. A resurgent Taliban today hold more Afghan territory than ever before, the civilian toll is at a record high, and Afghan military casualties are rising to a level that American commanders warn is unsustainable. In the Taliban’s deadliest assault on Afghan army troops, a handful of militants killed more than 140 soldiers last month at a military base in the northern province of Balkh, prompting the country’s defense minister and chief of army staff to resign.

The enemy’s enemy

Not only is the Taliban militia at its strongest, but also a Russia-organized coalition that includes Iran and China is cozying up to it. Faced with biting U.S.-led sanctions, Russia is aligning with the enemy’s enemy to weigh down the U.S. military in Afghanistan. Indeed, as Russian President Vladimir Putin seeks to expand the geopolitical chessboard on which Moscow can play against the U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, a new “Great Game” is unfolding in Afghanistan.

Almost three decades after Moscow ended its own disastrous Afghanistan war, whose economic costs eventually contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has sought to reemerge as an important player in Afghan affairs by embracing a thuggish force that it long viewed as a major terrorist threat — the Taliban. In effect, Russia is trading roles with the U.S. in Afghanistan: In the 1980s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan promoted jihad against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, with the Central Intelligence Agency training and arming thousands of Afghan mujahedeen — the violent jihadists from which al-Qaeda and the Taliban evolved.

Today, the growing strains in U.S.-Russia relations — with Trump saying “we’re not getting along with Russia at all, we may be at an all-time low” — threaten to deepen the American military quagmire in Afghanistan. Trump came into office wanting to befriend Russia yet, with the sword of Damocles hanging over his head over alleged election collusion with Moscow, U.S.-Russian ties have only deteriorated. Russia has signaled that it is in a position to destabilize the U.S.-backed government in Kabul in the way Washington has undermined Syrian President Bashar Assad’s Moscow-supported regime by aiding Syrian rebels. Gen. Nicholson has suggested that Russia has started sending weapons to the Taliban.

Against this background, the odds are stacked heavily against the U.S. reversing the worsening Afghanistan situation and “winning again,” as Trump wants, especially if his administration follows in the footsteps of the previous two U.S. governments by not recognizing Pakistan’s centrality in Afghan security. Trump’s renewed mission in Afghanistan will fail if Washington does not add sticks to its carrots-only approach toward the Pakistani military, which continues to aid the Taliban, the Haqqani network and other terrorist groups.

No counterterrorism campaign has ever succeeded when militants have enjoyed cross-border havens. The Taliban are unlikely to be routed or seek peace as long as they can operate from sanctuaries in Pakistan, where their top leaders are ensconced. Their string of battlefield victories indeed gives them little incentive to enter into serious peace negotiations.

Still, the U.S. has been reluctant to go after the Taliban’s command and control base in Pakistan in order to preserve the option of reaching a Faustian bargain with the militia. For eight years, Obama pursued the same failed strategy of using inducements, ranging from billions of dollars in aid to the supply of lethal weapons, to nudge the Pakistani military and its rogue Inter-Services Intelligence agency to target the Haqqani network and get the Taliban to the negotiating table. According to Obama’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard G. Olson, the U.S. has no “fundamental quarrel” with the Taliban and seeks a deal.

Troop surge

If the recent visit of Trump’s national security adviser, Gen. H.R. McMaster, to Afghanistan and Pakistan is any indication, a fundamental break with the Obama approach is still not on the cards. In fact, the Trump team has proposed reemploying the same tool that Obama utilized in vain — a troop surge, although at a low level.

To compound matters, Trump is showing himself to be a tactical, transactional president whose foreign policy appears guided by the axiom “Speak loudly and carry a big stick.” In dropping America’s largest non-nuclear bomb last month in Afghanistan’s eastern Nangarhar province, Trump was emboldened by the ease of his action days earlier in ordering missile strikes against a Syrian air base while eating dessert — “the most beautiful piece of chocolate cake that you’ve ever seen” — with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

It is easy to drop a massive bomb or do missile strikes and appear “muscular,” but it is difficult to figure out how to fix a broken policy. This is the dilemma Trump faces over Afghanistan. In the same Pakistan-bordering area where the “Mother of All Bombs” was dropped, two U.S. soldiers were killed in fighting just days later.

Unlike Obama, who spent eight years experimenting with various measures, extending from a troop surge to a drawdown, Trump does not have time on his side. Obama, with excessive optimism, declared in late 2014 that “the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.” The reverse happened: Security in Afghanistan worsened rapidly. The Taliban rebuffed his peace overtures, despite Washington’s moves to allow the group to establish a de facto diplomatic mission in Qatar and to trade five senior Taliban leaders jailed at Guantanamo Bay for a captured U.S. Army sergeant.

Today, the very survival of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s government is at stake. Problems are rapidly mounting for the beleaguered government, which has presided over steadily deteriorating security. Its hold on many districts looks increasingly tenuous even before the approaching summer brings stepped-up Taliban attacks.

The revival of the “Great Game” in Afghanistan, meanwhile, threatens to complicate an already precarious security situation in South, Central and Southwest Asia.

If the U.S. continues to experiment, it will court a perpetual war in Afghanistan, endangering a key base from where it projects power regionally. The central choice Trump must make is between seeking to co-opt the Taliban through a peace deal, as Obama sought, and going all out after its command and control network in Pakistan. An Afghanistan settlement is likely only when the Taliban has been degraded and decapitated.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including “Water, Peace, and War.”

A rogue neighbour’s new rogue act

BRAHMA CHELLANEY | DNA, April 17, 2017

Periodically, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) offers fresh evidence that it remains a rogue agency. This includes the year-long saga involving its abduction from Iran of a former Indian naval officer, Kulbhushan Jadhav, who was recently sentenced to death by a secret military court in Pakistan for being an Indian “spy”. The case indeed stands out as a symbol of the thuggish conduct of an irredeemably scofflaw state.

Just because Pakistan alleges that Jadhav was engaged in espionage against it cannot justify the ISI’s kidnapping of him from Iran or his secret, mock trial in a military court. Under the extra-constitutional military court system — established after the late 2014 Peshawar school attack — judicial proceedings are secret, civilian defendants are barred from engaging their own lawyers, and the “judges” (not necessarily possessing law degrees) render verdicts without being required to provide reasons.

The military courts show, if any evidence were needed, that decisive power still rests with the military generals, with the army and ISI immune to civilian oversight. In fact, the announcement that Jadhav had been sentenced to death with the Pakistani army chief’s approval was made by the military, not the government, despite its major implications for Pakistan’s relations with India.

Add to the picture the Pakistani military’s ongoing state-sponsored terrorism against India, Afghanistan and even Bangladesh. Jadhav’s sentencing was a deliberate — but just the latest — provocation against India by the military, which has orchestrated a series of terrorist attacks on Indian security bases since the beginning of last year. It is clear that Pakistan is in standing violation of every canon of international law.

The right of self-defence is embedded as an “inherent right” in the UN Charter. India is entitled to defend its interests against the terrorism onslaught by imposing deterrent costs on the Pakistani state and its terrorist agents, including the ISI.

Unfortunately, successive Indian governments have failed to pursue a consistent and coherent Pakistan policy. As a result, the Pakistani military feels emboldened to persist with its roguish conduct.

Like his predecessors, Manmohan Singh and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pursued a meandering policy toward the congenitally hostile Pakistan. Modi has played the Pakistan card politically at home but not lived up to his statements on matters ranging from Balochistan to the Indus Waters Treaty. Indeed, there has been visible backsliding on his stated positions. For example, the suspended Permanent Indus Commission has been revived.

The Modi government talks tough in public but, on policy, acts too cautiously. For example, it persuaded Rajeev Chandrasekhar to withdraw his private member’s bill in the Rajya Sabha for India to declare Pakistan as a state sponsor of terrorism. India has shied away from imposing any kind of sanctions on Pakistan or even downgrading the diplomatic relations.

When history is written, Modi’s unannounced Lahore visit on Christmas Day in 2015 will be viewed as a watershed. If the visit was intended to be a peace overture, its effect was counterproductive. Modi’s olive branch helped transform his image in Pakistani military circles from a tough-minded, no-nonsense leader that Pakistan must not mess with to someone whose bark is worse than his bite.

Within days of his return to New Delhi, the ISI scripted twin terrorist attacks on India’s forward air base at Pathankot and the Indian consulate in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan, as New Year’s gifts to Modi. Worse was India’s response: It shared intelligence with Pakistan about the Pakistani origins of the Pathankot attackers while the four-day siege of the base was still on and then hosted a Pakistani inquiry team — all in the naïve hope of winning Pakistan’s anti-terrorism cooperation. In effect, India shared intelligence with an agency that it should have branded a terrorist entity long ago — the ISI.

An emboldened Pakistani military went on to orchestrate more attacks, with the Indian inaction further damaging Modi’s strongman image. Subsequently, the deadly Uri army-base attack, by claiming the lives of 19 Indian soldiers, became Modi’s defining moment. It was the deadliest assault on an Indian military facility in more than a decade and a half. Sensing the danger of being seen as little more than a paper tiger, Modi responded with a limited but much-hyped cross-border military operation by para commandos against terrorist bases.

The Indian public, whose frustration with Pakistan had reached a tipping point, widely welcomed the surgical strike as a catharsis. The one-off strike, however, did not deter the Pakistani military, which later staged the attack on India’s Nagrota army base. Modi’s response to that attack was conspicuous silence.

Recurrent cross-border terror attacks by ISI have failed to galvanize India into devising a credible counterterrorism strategy. Employing drug traffickers, the ISI is also responsible for the cross-border flow of narcotics, which is destroying public health in India’s Punjab. In fact, the Pathankot killers — like the Gurdaspur attackers — came dressed in Indian army uniforms through a drug-trafficking route.

In reality, the Pakistani military is waging an undeclared war against an India that remains adrift and reluctant to avenge even the killing of its military personnel. There are several things India can do, short of a full-fledged war, to halt the proxy war. But India must first have clear strategic objectives and display political will.

Reforming the Pakistani military’s behaviour holds the key to regional peace. After all, all the critical issues — border peace, trans-boundary infiltration and terrorism, and nuclear stability — are matters over which the civilian government in Islamabad has no real authority because these are preserves of the Pakistani military.

The Jadhav case illustrates that, as long as New Delhi recoils from imposing deterrent costs on Pakistan, the military there will continue to up the ante against India. Indeed, it has turned Jadhav into a bargaining chip to use against India. The battle to reform against Pakistan’s roguish conduct is a fight India has to wage on its own by translating its talk into action.

The author is a strategic thinker and commentator.

Putin’s Dance with the Taliban

BRAHMA CHELLANEY

A column internationally syndicated by Project Syndicate.

Russia may be in decline economically and demographically, but, in strategic terms, it is a resurgent power, pursuing a major military rearmament program that will enable it to continue expanding its global influence. One of the Kremlin’s latest geostrategic targets is Afghanistan, where the United States remains embroiled in the longest war in its history.

Russia may be in decline economically and demographically, but, in strategic terms, it is a resurgent power, pursuing a major military rearmament program that will enable it to continue expanding its global influence. One of the Kremlin’s latest geostrategic targets is Afghanistan, where the United States remains embroiled in the longest war in its history.

Almost three decades after the end of the Soviet Union’s own war in Afghanistan – a war that enfeebled the Soviet economy and undermined the communist state – Russia has moved to establish itself as a central actor in Afghan affairs. And the Kremlin has surprised many by embracing the Afghan Taliban. Russia had long viewed the thuggish force created by Pakistan’s rogue Inter-Services Intelligence agency as a major terrorist threat. In 2009-2015, Russia served as a critical supply route for US-led forces fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan; it even contributed military helicopters to the effort.

Russia’s reversal on the Afghan Taliban reflects a larger strategy linked to its clash with the US and its European allies – a clash that has intensified considerably since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea spurred the US and Europe to impose heavy economic sanctions. In fact, in a sense, Russia is exchanging roles with the US in Afghanistan.

In the 1980s, US President Ronald Reagan used Islam as an ideological tool to spur armed resistance to the Soviet occupation. Reasoning that the enemy of their enemy was their friend, the CIA trained and armed thousands of Afghan mujahedeen – the jihadist force from which al-Qaeda and later the Taliban evolved.

Today, Russia is using the same logic to justify its cooperation with the Afghan Taliban, which it wants to keep fighting the unstable US-backed government in Kabul. And the Taliban, which has acknowledged that it shares Russia’s enmity with the US, will take whatever help it can get to expel the Americans.

Russian President Vladimir Putin hopes to impose significant costs on the US for its decision to maintain military bases in Afghanistan to project power in Central and Southwest Asia. As part of its 2014 security agreement with the Afghan government, it has secured long-term access to at least nine bases to keep tabs on nearby countries, including Russia, which, according to Putin’s special envoy on Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, “will never tolerate this.”

More broadly, Putin wants to expand the geopolitical chessboard, in the hope that he can gain sufficient leverage over the US and NATO to wrest concessions on stifling economic sanctions. Putin believes that, by becoming a major player in Afghanistan, Russia can ensure that America needs its help to extricate itself from the war there. This strategy aligns seamlessly with Putin’s approach in Syria, where Russia has already made itself a vital partner in any effort to root out the Islamic State (ISIS).

In cozying up to the Taliban, Putin is sending the message that Russia could destabilize the Afghan government in the same way the US, by aiding Syrian rebels, has undermined Bashar al-Assad’s Russian-backed regime. Already, the Kremlin has implicitly warned that supply of Western anti-aircraft weapons to Syrian rebels would compel Russia to arm the Taliban with similar capabilities. That could be a game changer in Afghanistan, where the Taliban now holds more territory than at any time since it was ousted from power in 2001.

Russia is involving more countries in its strategic game. Beyond holding a series of direct meetings with the Afghan Taliban, Russia has hosted three rounds of trilateral Afghanistan-related discussions with Pakistan and China in Moscow. A coalition to help the Afghan Taliban, comprising those three countries and Iran, is emerging.

General John Nicholson, the US military commander in Afghanistan, seeking the deployment of several thousand additional American troops, recently warned of the growing “malign influence” of Russia and other powers in the country. Over the past year, Nicholson told the US Senate Armed Services Committee, Russia has been “overtly lending legitimacy to the Taliban to undermine NATO efforts and bolster belligerents using the false narrative that only the Taliban are fighting [ISIS].”

The reality, Nicholson suggested, is that Russia’s excuse for establishing intelligence-sharing arrangements with the Taliban is somewhat flimsy. US-led raids and airstrikes have helped to contain ISIS fighters within Afghanistan. In any case, those fighters have little connection to the Syria-headquartered group. The Afghan ISIS comprises mainly Pakistani and Uzbek extremists who “rebranded” themselves and seized territory along the Pakistan border.

In some ways, it was the US itself that opened the way for Russia’s Afghan strategy. President Barack Obama, in his attempt to reach a peace deal with the Taliban, allowed it to establish a de facto diplomatic mission in Qatar and then traded five senior Taliban leaders who had been imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay for a captured US Army sergeant. In doing so, he bestowed legitimacy on a terrorist organization that enforces medieval practices in the areas under its control.

The US has also refused to eliminate militarily the Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan, even though, as Nicholson admitted, “[i]t is very difficult to succeed on the battlefield when your enemy enjoys external support and safe haven.” On the contrary, Pakistan remains one of the world’s largest recipients of US aid. Add to that the Taliban’s conspicuous exclusion from the US list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, and it is difficult for the US credibly to condemn Russia’s overtures to the Taliban and ties with Pakistan.

The US military’s objective of compelling the Taliban to sue for “reconciliation” was always going to be difficult to achieve. Now that Russia has revived the “Great Game” in Afghanistan, it may be impossible.

Shed the Indus albatross

Brahma Chellaney, The Times of India, March 20, 2017

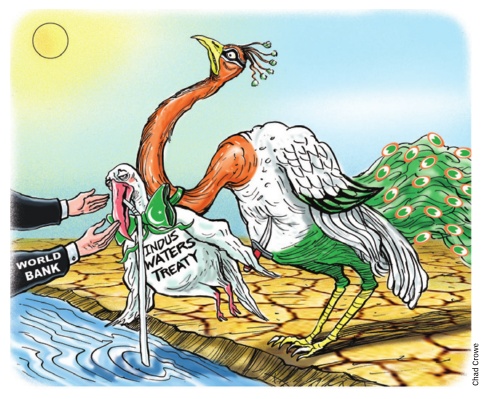

At a time when India is haunted by a deepening water crisis, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) hangs like the proverbial albatross from its neck. In 1960, in the naïve hope that water largesse would yield peace, India entered into a treaty that gave away the Indus system’s largest rivers as gifts to Pakistan.

Since then, that congenitally hostile neighbour, while drawing the full benefits from the treaty, has waged overt or covert aggression almost continuously and is now using the IWT itself as a stick to beat India with, including by contriving water disputes and internationalizing them.

A partisan World Bank, meanwhile, has compounded matters further. Breaching the IWT’s terms under which an arbitral tribunal cannot be established while the parties’ disagreement “is being dealt with by a neutral expert,” the Bank proceeded in November to appoint both a court of arbitration (as demanded by Pakistan) and a neutral expert (as suggested by India). It did so while admitting that the two concurrent processes could make the treaty “unworkable over time”.

World Bank partisanship, however, is not new: The IWT was the product of the Bank’s activism, with US government support, in making India embrace an unparalleled treaty that parcelled out the largest three of the six rivers to Pakistan and made the Bank effectively a guarantor in the treaty’s initial phase. With much of its meat in its voluminous annexes, this is an exhaustive, book-length treaty with a patently neo-colonial structure that limits India’s sovereignty to the basin of the three smaller rivers.

The Bank’s recent decision was made more bizarre by the fact that while the treaty explicitly permits either party to seek a neutral expert’s appointment, it specifies no such unilateral right for a court of arbitration. In 2010, such an arbitral tribunal was appointed with both parties’ consent. The neutral expert, however, is empowered to refer the parties’ disagreement, if need be, to a court of arbitration.

The uproar that followed the World Bank’s initiation of the dual processes forced it to “pause,” but not terminate, its legally untenable decision. Stuck with a mess of its own making, it is now prodding India to bail it out by compromising with Pakistan over the two moderate-sized Indian hydropower projects. But what Pakistan wants are design changes of the type it enforced years ago in the Salal project, resulting in that plant silting up. It is threatening to target other Indian projects as well.

Yet Indian policy appears adrift. Indeed, India is backsliding even on its tentative moves to deter Pakistani terrorism. For example, after last September’s Uri attack, it suspended the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) with Pakistan. Now the suspension has been lifted, allowing the PIC to meet in the aftermath of the state elections.

In truth, the suspension was just a charade, with the PIC missing no meeting. Prime Minister Narendra Modi reversed course in time for the PIC, which meets at least once every financial year, to meet before the current year ended on March 31 in order to prepare its annual report by the treaty-stipulated June 1 deadline. But while the suspension was widely publicized for political ends, the reversal happened quietly.

Much of the media also fell for another charade that Modi sought to play to the hilt in the Punjab elections: He promised to end Punjab’s water stress by utilizing India’s full IWT-allocated share of the waters. His government, however, has initiated not a single new project to correct India’s abysmal failure to tap its meagre 19.48% share of the Indus waters.

Instead, Modi has engaged in little more than eyewash: He has appointed a committee of secretaries, not to find ways to fashion the Indus card to reform Pakistan’s conduct, but farcically to examine India’s own rights under the IWT over 56 years after it was signed. The answer to India’s serious under-utilization of its share, which has resulted in Pakistan getting more than 10 billion cubic meters (BCM) yearly in bonus waters on top of its staggering 167.2 BCM allocation, is not a bureaucratic rigmarole but political direction to speedily build storage and other structures.

Despite Modi’s declaration that “blood and water cannot flow together,” India is reluctant to hold Pakistan to account by linking the IWT’s future to that renegade state’s cessation of its unconventional war. It is past time India shed its reticence.

Pakistan’s interest lies in sustaining a unique treaty that incorporates water generosity to the lower riparian on a scale unmatched by any other pact in the world. Yet it is undermining its own interest by dredging up disputes with India and running down the IWT as ineffective for resolving them. By insisting that India must not ask what it is getting in return but bear only the IWT’s burdens, even as it suffers Pakistan’s proxy war, Islamabad itself highlights the treaty’s one-sided character.

In effect, Pakistan is offering India a significant opening to remake the terms of the Indus engagement. This is an opportunity that India should not let go. The Indus potentially represents the most potent instrument in India’s arsenal — more powerful than the nuclear option, which essentially is for deterrence.

The writer is a geostrategist and author.

Time to stop the backsliding on Pakistan policy

Brahma Chellaney, Mail Today, March 11, 2017

Last year was an unusual year: Never before had so many Indian security bases come under attack by Pakistan-based terrorists in a single year. For example, the terrorist strike on the Pathankot air base was New Year’s gift to India, while the strike on the Indian Army’s Uri base represented a birthday gift for Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Furthermore, the number of Indian security personnel killed in gunbattles with terrorists in Jammu and Kashmir in 2016 was the highest in years.

Last year was an unusual year: Never before had so many Indian security bases come under attack by Pakistan-based terrorists in a single year. For example, the terrorist strike on the Pathankot air base was New Year’s gift to India, while the strike on the Indian Army’s Uri base represented a birthday gift for Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Furthermore, the number of Indian security personnel killed in gunbattles with terrorists in Jammu and Kashmir in 2016 was the highest in years.

In this light, it is remarkable that Modi is seeking to return to business as usual with Pakistan, now that the state elections are over in India and Pakistan-related issues have been sufficiently milked by him for political ends. Modi’s U-turn on the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) issue could mark the beginning of India’s backsliding.

After the Uri attack in September, his government, with fanfare, suspended the PIC. Now, quietly, that suspension has been lifted, and a PIC meeting will soon be held in Lahore. In reality, the suspension was just a sham because the PIC missed no meeting as a result. Its annual meeting in the current financial year is being held before the March 31 deadline.

The PIC was created by the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, the world’s most generous (and lopsided) water-sharing pact. The PIC decision indicates that Modi, despite vowing that “blood and water cannot flow together,” is not willing to abandon the treaty or even suspend its operation until Pakistan has terminated its proxy war by terror. The World Bank, in fact, is pressing the Modi government to use the PIC to reach a compromise with Pakistan over the latter’s demand for fundamental design changes in India’s Kishenganga and Ratle hydropower plants that could make these projects commercially unviable. Construction of the Ratle project has yet to begin.

The observable backsliding is also evident from other developments, including the appointment of a retired Pakistani diplomat, Amjad Hussain Sial, as the new secretary general of SAARC after India withdrew its objection. Modi is even keeping open the option of holding talks with his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif, in June on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Astana, Kazakhstan.

The Modi government’s reluctance to back up its words with action became conspicuous when it persuaded Rajeev Chandrasekhar to withdraw his private member’s bill in the Rajya Sabha to declare Pakistan as a state sponsor of terrorism. If India, the principal victim of Pakistani terrorism, is reluctant to designate Pakistan as a state sponsor of terrorism, can it realistically expect the U.S. to take the lead on that issue? Other powers might sympathize with India’s plight but India will not earn their respect through all talk and no action. The battle against Pakistan’s cross-border terrorism is India’s fight alone.

To be clear, the confused Pakistan policy predates the Modi government. Despite Pakistan’s unending aggression against India ever since it was created as the world’s first Islamic republic in the post-colonial era, successive Indian governments have failed to evolve a consistent, long-term policy toward that renegade country. Consequently, waging an unconventional war against India remains an effective, low-cost option for Pakistan.

A major plank on which Modi won the 2014 general election was a clear policy to defeat Pakistan’s proxy war. His blow-hot-blow-cold policy toward Pakistan, however, suggests that he has yet to evolve a coherent strategy to reform Pakistan’s roguish conduct. The key inflection point in Modi’s Pakistan policy came on Christmas Day in 2015 when he paid a surprise visit to Lahore mainly to grab international spotlight. If it yielded anything, it was the twin terrorist attacks just days later on the Pathankot base and the Indian consulate in Mazar-i-Sharif, setting in motion the ominous developments of 2016.

To be sure, Modi sought to salvage his credibility when in late September the Indian Army carried out surgical strikes on militants across the line of control in J&K. But it was always clear that a one-off operation like that would not tame Pakistan. India needs to keep Pakistan off balance through sustained pressure so that it has little leeway to pursue its goal to inflict death by a thousand cuts.

It is not too late for Modi to develop a set of policies that aim to impose punitive costs on Pakistan in a calibrated and gradually escalating manner, including through diplomatic, political and economic tools. If Pakistan can wage an unconventional war with a nuclear shield, a nuclear-armed India too can respond by taking the unconventional war to the enemy’s own land, including by exploiting Pakistan’s ethnic and sectarian fault lines, particularly in Baluchistan, Sind, Gilgit-Baltistan and the Pushtun regions. India must also up the ante by unambiguously linking the future of the iniquitous Indus treaty to Pakistan’s cessation of its aggression so that Islamabad no longer has its cake and eat it too. Like Lady Macbeth in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, no amount of Indus water can “wash this blood clean” from the hands of the Pakistani military generals.

Myanmar’s military has lately been engaged in a brutal campaign against the Rohingya, a long-marginalized Muslim ethnic minority group, driving hundreds of thousands to flee to Bangladesh, India, and elsewhere. The international community has rightly condemned the crackdown. But, in doing so, it has failed to recognize that Rohingya militants have been waging jihad in the country – a reality that makes it extremely difficult to break the cycle of terror and violence.

Rakhine State, where most of Myanmar’s Rohingya reside, is attracting jihadists from far and wide. Local militants are suspected of having ties with the Islamic State (ISIS), al-Qaeda, and other terrorist organizations. Moreover, they increasingly receive aid from militant-linked organizations in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The main insurgent group – the well-oiled Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, also known as Harakah al-Yaqin – is led by a Saudi-based committee of Rohingya émigrés.

The external forces fomenting insurgent attacks in Rakhine bear considerable responsibility for the Rohingyas’ current plight. In fact, it is the links between Rohingya militants and such external forces, especially terrorist organizations like ISIS, that have driven the government of India, where some 40,000 Rohingya have settled illegally, to declare that their entry poses a serious security threat. Even Bangladesh acknowledges Rohingya militants’ external jihadi connections.

But the truth is that Myanmar’s jihadi scourge is decades old, a legacy of British colonialism. After all, it was the British who, more than a century ago, moved large numbers of Rohingya from East Bengal to work on rubber and tea plantations in then-Burma, which was administered as a province of India until 1937.

In the years before India gained independence from Britain in 1947, Rohingya militants joined the campaign to establish Pakistan as the first Islamic republic of the postcolonial era. When the British, who elevated the strategy of “divide and rule” into an art, decided to establish two separate wings of Pakistan on either side of a partitioned India, the Rohingya began attempting to drive Buddhists out of the Muslim-dominated Mayu peninsula in northern Rakhine. They wanted the Mayu peninsula to secede and be annexed by East Pakistan (which became Bangladesh in 1971).

Failure to achieve that goal led many Rohingya to take up arms in a self-declared jihad. Local mujahedeen began to organize attacks on government troops and seize control of territory in northern Rakhine, establishing a state within a state. Just months after Myanmar gained independence in 1948, martial law was declared in the region; government forces regained territorial control in the early 1950s.

But Rohingya Islamist militancy continued to thrive, with mujahedeen attacks occurring intermittently. In 2012, bloody clashes broke out between the Rohingya and the ethnic Rakhines, who feared becoming a minority in their home state. The sectarian violence, in which rival gangs burned down villages and some 140,000 people (mostly Rohingya) were displaced, helped to transform the Rohingya militancy back into a full-blown insurgency, with rebels launching hit-and-run attacks on security forces.

Similar attacks have lately been carried out against security forces and, in some cases, non-Rohingya civilians, with the violence having escalated over the last 12 months. Indeed, it was a wave of coordinated predawn insurgent attacks on 30 police stations and an army base on August 25 that triggered the violent military offensive that is driving the Rohingya out of Rakhine.

Breaking the cycle of terror and violence that has plagued Myanmar for decades will require the country to address the deep-seated sectarian tensions that are driving Rohingya toward jihadism. Myanmar is one of the world’s most ethnically diverse countries. Its geographic position makes it a natural bridge between South and Southeast Asia, and between China and India.

But, internally, Myanmar has failed to build bridges among its various ethnic groups and cultures. Since independence, governments dominated by Myanmar’s Burman majority have allowed postcolonial nativism to breed conflict or civil war with many of the country’s minority groups, which have complained of a system of geographic apartheid.

The Rohingya face the most extreme marginalization. Viewed as outsiders even by other minorities, the Rohingya are not officially recognized as one of Myanmar’s 135 ethnic groups. In 1982, the government, concerned about illegal immigration from Bangladesh, enacted a law that stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship, leaving them stateless.

Successive governments have defended this approach, arguing that past secessionist movements indicate that the Rohingya never identified as part of the country. And, in fact, the common classification of Rohingya as stateless “Bengalis” mirrors the status of Rohingya exiles in the country of their dreams, Pakistan, where tens of thousands took refuge during the Pakistani military genocide that led to Bangladesh’s independence.

Still, the fact is that Myanmar’s failure to construct an inclusive national identity has allowed old ethnic rivalries to continue to fuel terrorism, stifling the resource-rich country’s potential. What Myanmar needs now is an equitable, federalist system that accommodates its many ethnic minorities, who comprise roughly a third of the population, but cover half of the total land area.

To this end, it is critical that Myanmar’s military immediately halt human-rights abuses in Rakhine. It will be impossible to ease tensions if soldiers are using disproportionate force, much less targeting civilians; indeed, such an approach is more likely to fuel than quell violent jihadism. But as the international community pressures Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi to take stronger action to protect the Rohingya, it is also vital to address the long history of Islamist extremism that has contributed to the ethnic group’s current plight.