Brahma Chellaney, The Times of India

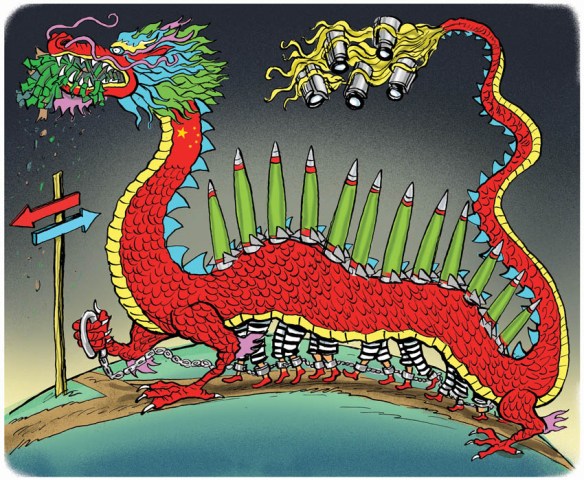

On 70th anniversary of PRC’s founding, the limits of its Party-led model are showing

Four decades ago, the Chinese Communist Party, under its new paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, decided to subordinate ideology to wealth creation, spawning a new aphorism, “To get rich is glorious.” The party’s central committee, disavowing Mao Zedong’s thought as dogma, embraced a principle that became Mr. Deng’s oft-quoted dictum, “Seek truth from facts.”

Mr. Mao’s death earlier in 1976 had triggered a vicious and protracted power struggle. When the diminutive Mr. Deng – once described by Mr. Mao as a “needle inside a ball of cotton” – finally emerged victorious at the age of 74, he hardly looked like an agent of reform.

But having been purged twice from the party during the Mao years – including once for proclaiming during the 1960s that “it doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice” – Mr. Deng seized the opportunity to usher in transformative change.

The Four Modernizations program under Mr. Deng remarkably transformed China, including spurring its phenomenal economic rise. China’s economy today is 30 times larger than it was three decades ago. Indeed, in terms of purchasing power parity, China’s economy is already larger than America’s.

Yet, four decades after it initiated reform, China finds itself at the crossroads, with its future trajectory anything but certain.

To be sure, when it celebrates in 2019 the 70th anniversary of its communist “revolution,” China can truly be proud of its remarkable achievements. An impoverished, backward country in 1949, it has risen dramatically and now commands respect and awe in the world.

China is today the world’s largest, strongest and longest-surviving autocracy. This is a country increasingly oriented to the primacy of the Communist Party. But here’s the paradox: The more it globalizes while seeking to simultaneously insulate itself from liberalizing influences, the more vulnerable it is becoming to unforeseen political “shocks” at home.

Its overriding focus on domestic order explains one unusual but ominous fact: China’s budget for internal security – now officially at US$196-billion – is larger than even its official military budget, which has grown rapidly to eclipse the defence spending of all other powers except the United States.

China’s increasingly repressive internal machinery, aided by a creeping Orwellian surveillance system, has fostered an overt state strategy to culturally smother ethnic minorities in their traditional homelands. This, in turn, has led to the detention of a million or more Muslims from Xinjiang in internment camps for “re-education.”

Untrammelled repression, even if effective in achieving short-term objectives, could sow the seeds of violent insurgencies and upheavals.

More broadly, China’s rulers, by showing little regard for the rights of smaller countries as they do for their own citizens’ rights, are driving instability in the vast Indo-Pacific region.

Nothing better illustrates China’s muscular foreign policy riding roughshod over international norms and rules than its South China Sea grab. It was exactly five years ago that Beijing began pushing its borders far out into international waters by pressing its first dredger into service for building artificial islands. The islands, rapidly created on top of shallow reefs, have now been turned into forward military bases.

The island-building anniversary is as important as the 40th economic-reform anniversary, because it is reminder that China never abandoned its heavy reliance since the Mao era on raw power.

In fact, no sooner had Mr. Deng embarked on reshaping China’s economic trajectory than he set out to “teach a lesson” to Vietnam, in the style of Mr. Mao’s 1962 military attack on India. The February-March 1979 invasion of Vietnam occurred just days after Mr. Deng – the “nasty little man,” as Henry Kissinger once called him – became the first Chinese communist leader to visit Washington.

A decade later, Mr. Deng brutally crushed a student-led, pro-democracy movement at home. He ordered the tank and machine-gun assault that came to be known as the Tiananmen massacre. According to a British government estimate, at least 10,000 demonstrators and bystanders perished.

Yet, the United States continued to aid China’s economic modernization, as it had done since 1979, when president Jimmy Carter sent a memo to various U.S. government departments instructing them to help in China’s economic rise.

Today, a fundamental shift in America’s China policy, with its broad bipartisan support, is set to outlast Donald Trump’s presidency. This underscores new challenges for China, at a time when its economy is already slowing and it has imposed tighter capital controls to prop up its fragile financial system and the yuan’s international value.

The international factors that aided China’s rise are eroding. The changing international environment also holds important implications for China domestically, including the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. Xi Jinping, who, in October 2017, ended the decades-old collective leadership system to crown himself China’s new emperor, now no longer looks invincible.

The juxtaposing of the twin anniversaries helps shine a spotlight on a fact obscured by China’s economic success: Mr. Deng’s refusal to truly liberalize China has imposed enduring costs on the country, which increasingly bends reality to the illusions that it propagates. The price being exacted for the failure to liberalize clouds China’s future, heightening uncertainty in the Asia-Pacific.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and author.

You must be logged in to post a comment.