By BRAHMA CHELLANEY

The Japan Times, April 18, 2012

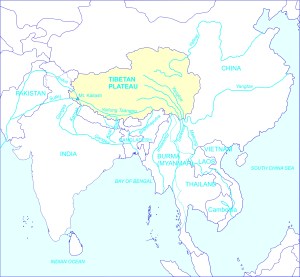

The Centrality of the Tibetan Plateau in Asia's Water Map

(c) Brahma Chellaney, "Water: Asia's New Battleground" (Georgetown University Press).

Dam building on shared rivers has emerged as the leading source of water disputes and tensions in Asia, the world’s driest continent whose freshwater availability is less than half the global annual average of 6,380 cubic meters per inhabitant. Dam-building activities by China and Central, South and Southeast Asian states have roiled inter-riparian relations, intensifying water discord and impeding broader regional cooperation and integration.

Dam building has largely petered out in the West, but continues in full swing in Asia.

According to international projections, the total number of dams in the developed countries in the next one decade is likely to remain about the same, while much of the dam building in the developing world, in terms of aggregate storage-capacity buildup, is expected to be concentrated in just one country — China. Indeed, about four-fifths of all dams currently under construction in Asia are just in China, which already boasts slightly more than half of all existing large dams in the world.

In the United States — the world’s second most dammed country after China — the rate of decommissioning of dams has overtaken the pace of building new ones. Yet the numerous new dam projects in Asia show that the damming of rivers is still an important priority for national and provincial policymakers. This reflects their insistence on engineering potential solutions to the water shortages.

Dams bring important benefits. If adequately sized and designed, dams can aid economic and social development by regulating water supply, controlling floods, facilitating irrigation and storing water in the wet season for release in the dry season. In addition, they can help generate hydroelectricity and bring drinking water to cities, when designed for such purposes.

But upstream dams on shared rivers in an era of growing water stress often carry broader political and social implications, especially because they can affect the quality and quantity of downstream flows. Dams, by often altering fluvial ecosystems and damaging biodiversity, also carry other environmental costs.

At a number of sites in Asia, dam building has triggered grassroots opposition over the submergence of land and the displacement of residents. Such opposition tends to be effectively stifled in autocracies. Democracies, by contrast, struggle to placate the local resistance.

For example, the future of the $5.62-billion Yanba Dam project in Japan remains uncertain. Popular opposition led to a two-year freeze before the project was recently resurrected by the government, although the ruling Democratic Party of Japan had labeled the dam in its election manifesto as a “wasteful public-works scheme.” Plans for this dam were conceived six decades ago, but public controversies have continued to weigh down the project.

The Yanba Dam — Japan’s largest dam-construction project by value — is designed to combat Agatsuma River flooding and supply drinking water to Tokyo and surrounding areas.

In another democracy, South Korea, the so-called Four Major Rivers Restoration Project launched by President Lee Myung Bak in early 2009 has proven a nationally divisive issue. The project has involved the building of more dams and barrages in a country that already boasts more than 800 large dams and 18,000 small irrigation reservoirs, with artificial lakes making up almost 95 percent of all the lakes.

The project’s high price tag — it will cost taxpayers almost $20 billion — has also fueled public controversies. The project was originally centered on the country’s four main rivers — the Han, the Nag Dong, the Kuem, and the Young San — but later the southern Seom Jin River was also added.

In India, a large, raucous democracy, such is the power of nongovernment organizations and citizens groups to organize grassroots protests that it has now become virtually impossible to build a large dam, blighting the promise of hydropower. Proof of this was the Indian government’s decision in 2010 to abandon three dam projects on the Bhagirathi River, including one midway. That project was scrapped on environmental grounds after authorities had already spent $139 million at the project site and ordered equipment worth $288 million. The decision represented a huge loss of taxpayer money.

The largest dam India has constructed since independence is the 2,000 megawatt (MW) Tehri, which pales in comparison to the giant Chinese projects, such as the more than nine-times-bigger Three Gorges Dam or even the new Chinese dams built or under construction on the Mekong.

The 1,450 MW Narmada Dam in west-central India has been under construction for decades. The project has sparked an unending war between environmental groups and authorities. Like Japan’s Yanba Dam, the Indian plan to harness the 1,300-km Narmada River dates back to the 1940s.

The legal, logistical, bureaucratic, political and NGO-activist hurdles the Narmada project has faced reflect the true reality in building any large dam in a country as politically diverse and open as India. Yet the country’s Supreme Court recently ordered the government to revive a decade-old plan to link up the important rivers in two separate grids — one in the north and the other in the south. Given India’s troubles over the Narmada Dam, it is an open question whether the grand river-linking plans will be realized.

In Southeast Asia, dam-building disputes fall in two categories. First, there is a clear divide between the lower-riparian states and China over the unilateral Chinese harnessing of the resources of the Mekong, with the smaller and weaker down-river states unable to persuade Beijing to halt or even slow its construction of dams on that transnational river. Second, dam building in the lower basin — although on a much smaller scale than by China — has also stoked controversies.

The damming plans of Laos, which wants to be the “battery” of Southeast Asia, have been driven by a desire to earn hydro-dollars through the export of electricity, mainly to China. Indeed, most of the planned Laotian and Cambodian dams involve Chinese financial, design or engineering assistance. Thailand’s own hydro-development plans have further muddied the picture.

Vietnam, located farthest downstream, has the most to lose. Laos, responding to growing regional concerns, agreed last year to defer building its largest project, the 1,260 MW Sayabouly Dam, until an expert review has been completed.

China’s construction of mega-dams, however, continues unabated. After recently commissioning the 4,200 MW Xiaowan, which dwarfs Paris’ Eiffel Tower in height, it is racing to complete yet another giant dam on the Mekong — the 5,850 MW Nuozhadu. The state-run HydroChina Corporation has unveiled a plan to build a dam more than two times as large as the Three Gorges Dam at Metog (“Motuo” in Chinese), close to the disputed, heavily militarized border with India.

Such is the growing interstate competition over water resources that even run-of-river projects have become a source of inter-riparian tensions, although, unlike multipurpose storage dams, they generally do not alter cross-border flows. Such dams are mostly small in scale and employ a river’s natural flow and elevation drop to produce electricity, without the aid of a large reservoir or dam. Even their environmental impact is minimal.

In recent years, Pakistan invoked provisions of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty to take one Indian run-of-river project to a World Bank-appointed neutral expert and another subsequently to the International Court of Arbitration. Whereas the neutral expert rejected Pakistan’s contentions, the arbitration proceedings are still on in the second case, the 330 MW Kishenganga plant.

Under this treaty, India has set aside 80 percent of the waters of the six-river Indus system for downstream Pakistan — the most generous water-sharing pact thus far in modern world history. India, however, is downriver to China, which rejects the very concept of water sharing.

Asia is the hub of the global water challenges. To contain the associated security risks, Asian states must build institutionalized water cooperation, based on transparency, information sharing, equitable distribution of benefits, dispute settlement, pollution control, and a mutual commitment to refrain from any project that could materially diminish transboundary flows.

Water is the most critical of all natural resources on which modern economies depend. Water scarcity and rapid economic advance cannot go hand-in-hand. Yet, with its per capita water availability falling to 1,582 cubic metres per year, India has become water-stressed.

Water is the most critical of all natural resources on which modern economies depend. Water scarcity and rapid economic advance cannot go hand-in-hand. Yet, with its per capita water availability falling to 1,582 cubic metres per year, India has become water-stressed.

Water, the most vital of all resources, has emerged as a key issue that will determine whether Asia is headed toward cooperation or competition. After all, the driest continent in the world is not Africa, but Asia, where availability of freshwater is not even half the global annual average of 6,380 cubic meters per inhabitant.

Water, the most vital of all resources, has emerged as a key issue that will determine whether Asia is headed toward cooperation or competition. After all, the driest continent in the world is not Africa, but Asia, where availability of freshwater is not even half the global annual average of 6,380 cubic meters per inhabitant.

You must be logged in to post a comment.