Beijing’s military advance into Bhutan-claimed territory leaves New Delhi floundering, raising concern over India’s own borders.

China’s CCTV in August shows a target exploding during a live-fire drill by the Chinese army near its border with India. © CCTV/AP

Brahma Chellaney, Nikkei Asian Review

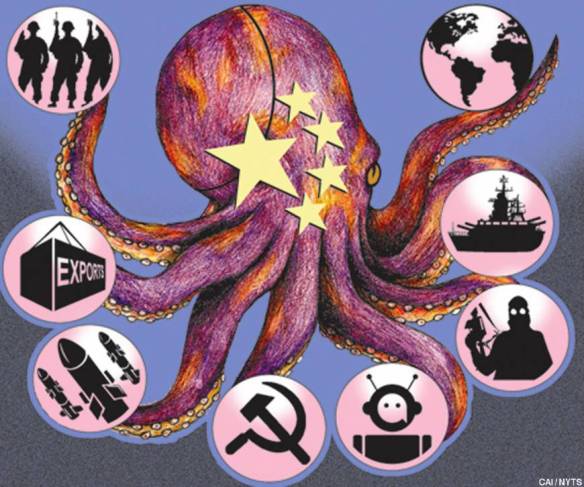

Operating in the threshold between peace and war, China has pushed its borders far out into international waters in the South China Sea in a way no other power has done elsewhere. Less known is that China is using a similar strategy in the Himalayas to alter facts on the ground — meter by meter — without firing a single shot.

India is facing increasingly persistent Chinese efforts to intrude into its desolate borderlands. China, however, has not spared even one of the world’s smallest countries, Bhutan, which has barely 8,000 men in its security forces. In the disputed Himalayan plateau of Doklam, claimed by both Bhutan and China, the People’s Liberation Army has incrementally changed the status quo since last fall.

Doklam became a defining event in a 10-week standoff between Chinese and Indian troops last summer after the PLA started building a highway on that plateau to the India border: For the first time since China’s success in the South China Sea, a rival power stalled Chinese construction activity to change the status quo in a disputed territory.

India intervened as Bhutan’s security guarantor to thwart a threat to its own security. Despite almost daily Chinese threats to “teach it a lesson,” India refused to back down, forcing a humiliated Beijing to eventually accept a mutual-withdrawal deal to end the standoff with a country it sees as economically and militarily inferior.

But as happened with the 2012 U.S.-brokered deal for Chinese and Philippine naval vessels to withdraw from around the Scarborough Shoal, China did not faithfully comply with the Doklam accord. If anything, China applied the Scarborough “model” to Doklam — agree to disengage and, after the standoff is over, quietly send in forces to occupy the territory.

Doklam thus illustrates that while India may be content with a tactical win, China has the perseverance and guile to win at the strategic level. Camouflaging offense as defense, China hews to ancient military theorist Sun Tzu’s advice, “The ability to subdue the enemy without any battle is the ultimate reflection of the most supreme strategy.” As Sun Tzu said, “All warfare is based on deception.”

India tried for months to obfuscate the PLA’s increasing control of Doklam so as not to dilute the “victory” it had sold to its public. Even as commercially available satellite images showed China’s rapidly expanding military infrastructure in Doklam, India’s foreign ministry tried pulling the wool over the public’s eyes by repeatedly saying there were “no new developments at the faceoff site or its vicinity,” located at the plateau’s southern edge. Meanwhile, China continued to build permanent military structures and forward deploy troops across much of Doklam.

This month, Indian Defense Minister Nirmala Sitharaman grudgingly admitted China has constructed helipads and other military structures in Doklam so as to “maintain” troop deployments even in winter. Previously, there were no force deployments or permanent military structures on the uninhabited plateau, which was visited by nomadic shepherds and Bhutanese and Chinese mobile patrols other than in the harsh winter.

To be sure, China has dictated a Hobson’s choice to India on Doklam, like it did to the Philippines over Scarborough: Go along with the changed status quo or face the risk of open war. Clearly, New Delhi didn’t anticipate that an end to the faceoff would result in rapid Chinese encroachments that now virtually preclude India intervening again in Doklam at Bhutan’s behest.

In effect, Beijing has shown Bhutan that India cannot guarantee its territorial integrity.

China’s objective unmistakably is to undercut India’s influence in Bhutan in the way Beijing has succeeded in another Himalayan nation, Nepal, where a Chinese-backed communist government took office earlier this year. It was Beijing that persuaded Nepal’s two main communist parties to overcome their bitter squabbles and join hands in national and local elections.

China’s new control over much of Doklam, however, effectively overturns the land-swap deal it has long offered Bhutan. Under the offer, the tiny kingdom was to cede its claim to that plateau in return for Beijing renouncing its claim to a slice of northern Bhutan.

Beijing has held some 24 rounds of border talks with Bhutan since 1984, just as its negotiations with India on territorial and boundary issues have gone on interminably since 1980 without tangible progress. In fact, the largest real estate China covets in Asia is in India — Arunachal Pradesh, a resource-rich Himalayan territory almost three times as large as Taiwan.

Today, China has stepped up military pressure on India, including beefing up its ground and air assets in the Himalayan region. The Indian government recently told Parliament that the number of Chinese military intrusions into India’s vulnerable borderlands jumped 56% in one year — from 273 in 2016 to 426 in 2017, or more than one per day. It seems that just as China’s trade surplus with India has doubled since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014, its border incursions are also on a similar rising trajectory.

India’s perennially reactive mode allows the PLA to keep the initiative in the Himalayas. More fundamentally, China — by mounting strategic pressure on multiple Indian flanks while raking in a fast-growing trade surplus (currently running at nearly $5 billion a month) — is able to have its cake and eat it too.

Add to the picture another important element of China’s Himalayan strategy — reengineering transboundary flows of rivers originating in Tibet through dams and other projects. A third of India’s total freshwater supply comes from rivers that start in Tibet. Last year, China breached two bilateral accords with India by withholding upstream river flow data, which is necessary for flood forecasting and warning. Supply of such data could have prevented some of the deaths in the record flooding that ravaged India’s northeast.

Some 67 years after China eliminated the historical buffer with India by annexing Tibet, it is transforming Himalayan geopolitics to its advantage. China’s strategic penetration of Nepal, which has an open border with India permitting passport-free passage, carries major implications for Indian security. Having lost the outer buffer, Tibet, India now risks losing the inner buffer, Nepal.

In the absence of a coherent strategy to counter China’s aggressive Himalayan strategy, an increasingly defensive India has now sought to make peace with Beijing. For example, it not only advised its officials to stay away from events marking the 60th anniversary this month of the Dalai Lama’s flight to India, but also got Tibetan exiles to move those events from New Delhi to remote Dharamsala, in the Himalayan foothills. Modi’s attention is focused on returning to power in the next national election, which is due to be held in April-May 2019 but might be advanced to this year-end.

Just when Chinese President Xi Jinping’s lurch toward one-man rule has led to a rethink in the West on its relationship with China, India has signaled its intent to go soft on China, with its foreign ministry saying that New Delhi was willing to develop relations with Beijing “based on commonalities.” Salvaging Modi’s China visit for last September’s BRICS (Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa) summit prompted New Delhi to cut the Doklam deal with Beijing, paving the way for the Chinese advance into the plateau. Now Modi is again set to go to China, this time for a bilateral summit with Xi. But India will likely not only come away empty-handed from its new propitiatory approach but also give cover to China’s designs against it.

Brahma Chellaney, a geostrategist and author, is professor of strategic studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research.

You must be logged in to post a comment.