Brahma Chellaney, Panorama Journal, Vol. 01/2018

In the four years that he has been in office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has animated domestic politics in India and the country’s foreign policy by departing often from conventional methods and shibboleths. A key question is whether the Modi era will mark a defining moment for India, just as the 1990s were for China and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s return as prime minister has been for Japan. The answer to that question is still not clear. What is clear, however, is that Modi’s ascension to power has clearly changed Indian politics and diplomacy.

Even before Modi’s Bharatiya Janata (Indian People’s) Party, or BJP, won the May 2014 national election, India’s fast-growing economy and rising geopolitical weight had significantly increased the country’s international profile. India was widely perceived to be a key “swing state” in the emerging geopolitical order. Since the start of this century, India’s relationship with the United States (US) has gradually but dramatically transformed. India and the US are now increasingly close partners. The US holds more military exercises with India every year than with any other country, including Britain. In the last decade, the US has also emerged as the largest seller of weapons to India, leaving the traditional supplier, Russia, far behind.

Modi’s pro-market economic policies, tax reforms, defence modernisation and foreign-policy dynamism have not only helped to further increase India’s international profile, but also augur well for the country’s economic-growth trajectory and rising strength. However, India’s troubled neighbourhood, along with its spillover effects, has posed a growing challenge for the Modi government. The combustible neighbourhood has underscored the imperative for India to evolve more dynamic and innovative approaches to diplomacy and national defence. For example, with its vulnerability to terrorist attacks linked to its location next to the Pakistan-Afghanistan belt, India has little choice but to prepare for a long-term battle against the forces of Islamic extremism and terrorism. Similarly, India’s ability to secure its maritime backyard, including its main trade arteries in the Indian Ocean region, will be an important test of its maritime strategy and foreign policy, especially at a time when an increasingly powerful and revisionist China is encroaching in India’s maritime space.

Modi’s Impact on Domestic Politics

Modi went quickly from being a provincial leader to becoming the prime minister of the world’s largest democracy. In fact, he rode to power in a landslide national-election victory that gave India the first government since the 1980s to be led by a party enjoying an absolute majority on its own in Parliament. The period since the late 1980s saw a series of successive coalition governments in New Delhi. Coalition governments became such a norm in India that the BJP’s success in securing an absolute majority in 2014 surprised even political analysts.

What factors explain the sudden rise of Modi? One factor clearly was the major corruption scandals that marred the decade-long rule of the preceding Congress Party-led coalition government headed by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The national treasury lost tens of billions of dollars in various corruption scandals. What stood out was not just the tardy prosecution process to bring to justice those responsible for the colossal losses but also the lack of sincere efforts to recoup the losses. The pervasive misuse of public office for private gain was seen by the voters as sapping India’s strength.

Modi, as the long-serving top elected official of the western Indian state of Gujarat, had provided a relatively clean administration free of any major corruption scandal. That stood out in contrast to Singh’s graft-tainted federal government. However, Hindu-Muslim riots in 2002 in Gujarat turned Modi into a controversial figure, with his opponents alleging that his state administration looked the other way as Hindu rioters attacked Muslims in reprisal for a Muslim mob setting a passenger train on fire. The political controversy actually prompted the US government in 2005 to revoke Modi’s visa over the unproven allegations that he connived in the Hindu-Muslim riots. Even after India’s Supreme Court found no evidence to link Modi to the violence, the US continued to ostracise him, reaching out to him only on the eve of the 2014 national election when he appeared set to become the next prime minister.

Modi’s political career at the provincial level was actually built on his success in coordinating relief work in his home state of Gujarat in response to a major 2001 earthquake there. Months after his relief work, Modi became the state’s chief minister, or the top elected official.

His party, the BJP, has tacitly espoused the cause of the country’s Hindu majority for long while claiming to represent all religious communities. The BJP sees itself as being no different than the Christian parties that emerged in Western Europe in the post-World War II era. The Christian parties in Western Europe, such as Germany’s long-dominant Christian Democratic Union (CDU), played a key role in Western Europe’s post-war recovery and economic and political integration.[1] Modi himself has subtly played the Hindu card to advance his political ambitions at the national level.

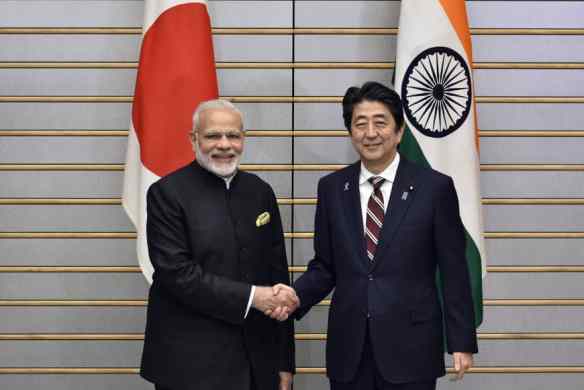

One can also draw a parallel between the prolonged period of political drift and paralysis in India that led to the national rise of Modi in 2014 and Japan’s six years of political instability that paved the way for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s return to power in 2012. Just as Abe’s return to power reflected Japan’s determination to reinvent itself as a more competitive and confident country, Modi’s election victory reflected the desire of Indians for a dynamic, assertive leader to help revitalise their country’s economy and security.

In fact, both Modi and Abe have focused on reviving their country’s economic fortunes, while simultaneously bolstering its defences and strengthening its strategic partnerships with likeminded states in order to promote regional stability and block the emergence of a Sino-centric Asia. Modi’s policies mirror Abe’s soft nationalism, market-oriented economics, and new “Asianism”, including seeking closer ties with Asian democracies to create a web of interlocking strategic partnerships. Until Modi became the first prime minister born after India gained independence in 1947, the wide gap between the average age of Indian political leaders and Indian citizens was conspicuous. That constitutes another parallel with Abe, who is Japan’s first prime minister born after World War II.

To be sure, there is an important difference in terms of the two leaders’ upbringing. Modi rose from humble beginnings to lead the world’s most-populous democracy.[2] Abe, on the other hand, boasts a distinguished political lineage as the grandson and grandnephew of two former Japanese prime ministers and the son of a former foreign minister. In fact, Modi rode to victory by crushing Rahul Gandhi’s dynastic aspirations.

Since he became prime minister, Modi has led the BJP to a string of victories in elections in a number of states, making the party the largest political force in the country without doubt. Under his leadership, the traditionally urban-focused BJP has significantly expanded its base in rural areas and among the socially disadvantaged classes. His skills as a political tactician steeped in cold-eyed pragmatism have held him in good stead. Modi, however, has become increasingly polarising. Indian democracy today is probably as divided and polarised as US democracy.

Politically, Modi has blended strong leadership, soft nationalism, and an appeal to the Hindu majority into an election-winning strategy. Playing the Hindu card, for example, helped the BJP to sweep the northern Hindi-speaking heartland in the 2014 national election and ride to victory in the subsequent state election in Uttar Pradesh, the country’s largest state. But use of that card, not surprisingly, has fostered greater divisiveness. Despite playing that card, the BJP, however, has done little for the Hindu majority specifically, thus reinforcing criticism that it cleverly uses the card to achieve electoral gains.

The BJP’s electoral successes, meanwhile, have prompted the opposition leader, Rahul Gandhi, to take a leaf out of Modi’s playbook by seeking to similarly boost his popularity among the Hindu majority. While campaigning in the December 2017 Gujarat state election, for example, Rahul Gandhi visited many Hindu temples. This new strategy resulted in his Congress Party, which has traditionally banked on the Muslim vote, significantly improving its strength in the Gujarat state legislature, although the BJP managed to hold on to power in a close election contest.

More fundamentally, Modi’s political rise had much to do with the Indian electorate’s yearning for an era of decisive government. Before becoming prime minister, Modi – a darling of business leaders at home and abroad – promised to restore rapid economic growth, saying there should be “no red tape, only red carpet” for investors.[3] He also pledged a qualitative change in governance and assured that the corrupt would face the full force of law. But, in office, has Modi really lived up to his promises?

Although he came to office with a popular mandate to usher in major changes, his record in power has been restorative rather than transformative. The transformative moment usually comes once in a generation. Modi failed to seize that moment. He seems to believe in incrementalism, not transformative change. His sheen has clearly dulled, yet his mass appeal remains unmatched in the country.

New Dynamism but also New Challenges in Foreign Policy

India faces major foreign-policy challenges, which by and large predate Modi’s ascension to power. India is home to more than one-sixth of the world’s population, yet it punches far below its weight. A year before Modi assumed office, an essay in the journal Foreign Affairs, titled “India’s Feeble Foreign Policy,” focused on how the country is resisting its own rise, as if the political miasma in New Delhi had turned the country into its own worst enemy.[4]

When Modi became prime minister, many Indians hoped that he would give a new direction to foreign relations at a time when the gap between India and China in terms of international power and stature was growing significantly. In fact, India’s influence in its own strategic backyard – including Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and the Maldives – has shrunk. Indeed, Bhutan remains India’s sole pocket of strategic clout in South Asia.

India also confronts the strengthening nexus between its two nuclear-armed regional adversaries, China and Pakistan, both of which have staked claims to substantial swaths of Indian territory and continue to collaborate on weapons of mass destruction. In dealing with these countries, Modi has faced the same dilemma that has haunted previous Indian governments: the Chinese and Pakistani foreign ministries are weak actors. The Communist Party and the military shape Chinese foreign policy, while Pakistan is effectively controlled by its army and intelligence services, which still use terror groups as proxies. Under Modi, India has faced several daring terrorist attacks staged from Pakistan, including on Indian military facilities.

One Modi priority after assuming office was restoring momentum to the relationship with the United States, which, to some extent, had been damaged by grating diplomatic tensions and trade disputes while his predecessor was in office. While Modi has been unable to contain cross-border terrorist attacks from Pakistan or stem Chinese military incursions across the disputed Himalayan frontier, he has managed to lift the bilateral relationship with the US to a new level of engagement. He has enjoyed a good personal relationship with US President Donald Trump, like he had with Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama.

Modi considers close ties with the US as essential to the advancement of India’s economic and security interests. The US, for its part, sees India as central to its Indo-Pacific strategy. As the White House’s national security strategy report in December 2017 put it, “A geopolitical competition between free and repressive visions of world order is taking place in the Indo-Pacific region. The region, which stretches from the west coast of India to the western shores of the United States, represents the most populous and economically dynamic part of the world […] We welcome India’s emergence as a leading global power and stronger strategic and defence partner.”[5]

More broadly, Modi’s various steps and policy moves have helped highlight the trademarks of his foreign policy – from pragmatism and lucidity to zeal and showmanship. They have also exemplified his penchant for springing diplomatic surprises. One example was his announcement during a China visit to grant Chinese tourists e-visas on arrival, an announcement that caught by surprise even his foreign secretary, who had just said at a media briefing that there was “no decision” on the issue. Another example was in Paris, where Modi announced a surprise decision to buy 36 French Rafale fighter-jets.

Modi is a realist who loves to play on the grand chessboard of geopolitics. He is seeking to steer foreign policy in a direction that helps to significantly aid his strategy to revitalise the country’s economic and military security. At least five things stand out about his foreign policy.

First, Modi has invested considerable political capital – and time – in high-powered diplomacy. No other prime minister since the country’s independence participated in so many bilateral and multilateral summit meetings in his first years in office. Critics contend that Modi’s busy foreign policy schedule leaves him restricted time to focus on his most-critical responsibility – domestic issues, which will define his legacy.

Second, pragmatism is the hallmark of the Modi foreign policy. Nothing better illustrates this than the priority he accorded, soon after coming to office, to adding momentum to the relationship with America, despite the US having heaped visa-denial humiliation on him over nine years. In his first year in office, he also went out of his way to befriend India’s strategic rival, China, negating the early assumptions that he would be less accommodating toward Beijing than his predecessor. With China increasingly assertive and unaccommodating, Modi’s gamble failed to pay off. Yet, in April 2018, Modi made a fresh effort to “reset” relations with China and held an informal summit meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in the central Chinese city of Wuhan.

Third, Modi has sought to shape a non-doctrinaire foreign-policy approach powered by ideas. He has taken some of his domestic policy ideas (such as “Make in India” and “Digital India”) to foreign policy, as if to underscore that his priority is to revitalise India economically. By simultaneously courting different major powers, Modi has also sought to demonstrate his ability to forge partnerships with rival powers and broker cooperative international approaches in a rapidly changing world.

In fact, Modi’s foreign policy is implicitly attempting to move India from its long-held nonalignment to a contemporary, globalised practicality. In essence, this means that India – a founding leader of the nonaligned movement – could become more multi-aligned and less nonaligned. Building close partnerships with major powers to pursue a variety of interests in diverse settings will not only enable India to advance its core priorities but also will help it to preserve strategic autonomy, in keeping with the country’s longstanding preference for policy independence.

Nonalignment suggests a passive approach, including staying on the sidelines. Being multi-aligned, on the other hand, permits a proactive approach. Being pragmatically multi-aligned seems a better option for India than remaining passively non-aligned. A multi-aligned India is already tilting more toward the major democracies of the world, as the resurrected Australia-India-Japan-US quadrilateral (or “quad”) grouping underscores. Still, India’s insistence on charting an independent course is reflected in its refusal to join American-led financial sanctions against Russia.

Meanwhile, a Modi-led India has not shied away from building strategic partnerships with countries around China’s periphery to counter that country’s creeping strategic encirclement of India. New Delhi’s resolve was apparent when Modi tacitly criticised China’s military buildup and encroachments in the South China Sea as evidence of an “18th-century expansionist mindset.” India’s “Look East” policy, for its part, has graduated to an “Act East” policy, with the original economic logic of “Look East” giving way to a geopolitical logic. The thrust of the new “Act East” policy – unveiled with US blessings – is to re-establish historically close ties with countries to India’s east so as to contribute to building a stable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region. As Modi said in an op-ed published in 27 ASEAN newspapers on 26 January 2018 (the day, in a remarkable diplomatic feat, India hosted the leaders of all 10 ASEAN states as chief guests at its Republic Day parade), “Indians have always looked East to see the nurturing sunrise and the light of opportunities. Now, as before, the East, or the Indo-Pacific region, will be indispensable to India’s future and our common destiny.”[6]

Fourth, Modi has a penchant for diplomatic showmanship, reflected not only in the surprises he has sprung but also in the kinds of big-ticket speeches he has given abroad, often to chants of “Modi, Modi” from the audience. Like a rock star, he unleashed Modi-mania among Indian-diaspora audiences by taking the stage at New York’s storied Madison Square Garden, at Sydney’s sprawling Allphones Arena, and at Ricoh Coliseum, a hockey arena in downtown Toronto. When permission was sought for a similar speech event in Shanghai during Modi’s 2015 China visit, an apprehensive Chinese government, which bars any public rally, relented only on the condition that the event would be staged in an indoor stadium.

To help propel Indian foreign policy, Modi has also injected a personal touch. Indeed, Modi has used his personal touch with great effect, addressing leaders ranging from Obama to Abe by their first name and building an easy relationship with multiple world leaders. In keeping with his personalised stamp on diplomacy, Modi has relied on bilateral summits to open new avenues for cooperation and collaboration. At the same time, underscoring his nimble approach to diplomacy, he has shown he can think on his feet. The speed with which he rushed aid and rescue teams to an earthquake-battered Nepal, as well as dispatched Indian forces to evacuate Indian and foreign nationals from Nepal and conflict-torn Yemen, helped to raise India’s international profile, highlighting its capacity to respond swiftly to natural and human-induced disasters.

Fifth, it is scarcely a surprise that, given this background, Modi has put his own stamp on Indian foreign policy. The paradox is that Modi came to office with little foreign policy experience, yet he has demonstrated impressive diplomatic acumen, including taking bold steps and charting a vision for building a greater international role for India.

The former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright famously said, “The purpose of foreign policy is to persuade other countries to do what we want or, better yet, to want what we want.”[7] How has Modi’s foreign policy done when measured against such a standard of success? One must concede that, in terms of concrete results, Modi’s record thus far isn’t all that impressive. His supporters, however, would say that dividends from a new direction in foreign policy flow slowly and that he has been in office for just four years.

To be sure, a long period of strategic drift under coalition governments undermined India’s strength in its own backyard. Modi, however, has not yet been able to recoup the country’s losses in its neighbourhood. The erosion of India’s influence in its backyard holds far-reaching implications for its security, underscoring the imperative for a more dynamic, forward-looking foreign policy and a greater focus on its immediate neighbourhood. China’s strategic clout, for example, is increasingly on display even in countries symbiotically tied to India, such as Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. If China established a Djibouti-type naval base in the Maldives or Pakistan, it would effectively open an Indian Ocean front against India in the same quiet way that it opened the trans-Himalayan threat under Mao Zedong by gobbling up Tibet, the historical buffer. China has already leased several tiny islands in the Maldives and is reportedly working on a naval base adjacent to Pakistan’s Chinese-built Gwadar port.

To be sure, Modi has injected dynamism and motivation in diplomacy.[8] But he has also highlighted what has long blighted the country’s foreign policy – ad hoc and personality-driven actions that confound tactics with strategy. Institutionalised and integrated policymaking is essential for a robust diplomacy that takes a long view. Without healthy institutionalised processes, policy will tend to be ad hoc and shifting, with personalities at the helm having an excessive role in shaping thinking, priorities and objectives. If foreign policy is shaped by the whims and fancies of personalities who hold the reins of power, there will be a propensity to act in haste and repent at leisure, as has happened in India repeatedly since the time of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was in office for 17 years.

Today, India confronts a “tyranny of geography” – that is, serious external threats from virtually all directions. To some extent, it is a self-inflicted tyranny. India’s concerns over China, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives stem from the failures of its past policies. An increasingly unstable neighbourhood also makes it more difficult to promote regional cooperation and integration. With its tyranny of geography putting greater pressure on its external and internal security, India needs to develop more innovative approaches to diplomacy. The erosion of its influence in its own backyard should serve as a wake-up call. Only through forward thinking can India hope to ameliorate its regional-security situation and play a larger global role. Otherwise, it will continue to be weighed down by its region.

While India undoubtedly is injecting greater realism in its foreign policy, it remains intrinsically cautious and reactive, rather than forward-looking and proactive. India has not fully abandoned its quixotic traditions. India’s tradition of realist strategic thought is probably the oldest in the world.[9] The realist doctrine was propounded by the strategist Kautilya, also known as Chanakya, who wrote the Arthashastra before Christ; this ancient manual on great-power diplomacy and international statecraft remains a must-read classic. Yet India, ironically, appears to have forgotten its own realist strategic thought.

Concluding Observations

India is more culturally diverse than the entire European Union – but with twice as many people. It is remarkable that India’s democracy has thrived despite such diversity. Yet, like the US, India has become politically polarised. And like Trump, Modi draws strong reactions – in support of him or against him. When Modi won the 2014 national election, critics said they feared his strongman tendencies – a fear they still profess. But in office, Modi has been anything but strong or aggressive in his policies. For example, his foreign policy and his domestic policies, especially economic policy, have been cautious and tactful. However, the “strongman” tag that critics have given Modi helps to obscure his failure to improve governance in India. On his watch, for example, India’s trade deficit with China has doubled to almost $5 billion a month.

Prudent gradualism, however, remains the hallmark of Modi’s approach in diplomacy and domestic policy. For example, to underpin India’s position as the world’s fastest-growing developing economy, Modi has preferred slow but steady progress on reforms, an approach that Arvind Subramanian, the government’s chief economic adviser, dubbed “creative incrementalism.” Many in India, of course, would prefer a bolder approach. But as a raucous democracy, India has to pay a “democracy tax” in the form of slower decision-making and pandering to powerful electoral constituencies. For example, under Modi, India’s bill for state subsidies has risen sharply.

A dynamic foreign policy can be built only on the foundation of a strong domestic policy, a realm where Modi must overcome political obstacles to shape a transformative legacy. If India is to emerge as a global economic powerhouse, Modi must make economic growth his first priority. Another imperative is for India to reduce its spiralling arms imports by developing an indigenous defence industry. However, Modi’s “Make in India” initiative has yet to take off, with manufacturing’s share of India’s GDP actually contracting.

As a shrewd politician, Modi has shown an ability to deftly recover from a setback. For example, he came under withering criticism when, while meeting Obama in early 2015 in New Delhi, he wore a navy suit with his name monogrammed in golden stripes all over it. Critics accused him of being narcissistic, while one politician went to the extent of calling him a “megalomaniac.” But by auctioning off the suit, Modi quickly cauterised a political liability. The designer suit was auctioned for charity, fetching INR 43.1 million ($693,234).

To many, Modi seems politically invincible at home, floating above the laws of political gravity. But, as happens in any democracy, any leader’s time eventually runs out. Modi suddenly appeared vulnerable in last December’s state elections in his native state of Gujarat but his party managed to retain power, although with a reduced majority. Until his political stock starts to irreversibly diminish, Modi will continue to dominate the Indian political scene, playing an outsize role. At present, though, there is no apparent successor to Modi.

Professor Brahma Chellaney is a professor of strategic studies at the independent Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi and an affiliate with the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King’s College London. As a specialist on international strategic issues, he held appointments at Harvard University, the Brookings Institution, the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, and the Australian National University. He is the author of nine books, including an international bestseller, Asian Juggernaut (New York: Harper Paperbacks, 2010). His last book was Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

[1] John Murray, “Christian Parties in Western Europe,” Studies, Vol. 50, No. 198 (Summer 1961).

[2] Andy Marino, Narendra Modi: A political Biography (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 2014).

[3] Economic Times, “Red carpet, not red tape for investors is the way out of economic crisis,” Interview with Narendra Modi, June 7, 2012.

[4] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “India’s Feeble Foreign Policy: A Would-Be Great Power Resists Its Own Rise,” Foreign Affairs (May/June 2013).

[5] White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: December 2017), available at: https://goo.gl/CWQf1t.

[6] Narendra Modi, “Shared values, common destiny,” The Straits Times, January 26, 2018, available at: http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/shared-values-common-destiny.

[7] Madeleine Albright, The Mighty and the Almighty (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007).

[8] Alyssa Ayres, Our Time Has Come: How India is Making Its Place in the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[9] Aparna Pande, From Chanakya to Modi: Evolution of India’s Foreign Policy (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 2017).

You must be logged in to post a comment.