Political malaise at home, by exposing chinks in the US armor, is fraying America’s global image and contributing to the decline of US global leadership. Alas, the attempt to assassinate Trump will likely widen domestic divisions and make political discourse more toxic.

Brahma Chellaney, OPEN magazine

The United States, which believes it is the leader of the ‘free world’ and the guardian of the ‘rules-based order’, faces a deepening political crisis at home that has engulfed its leadership and democracy. Lawfare (or using the legal system as a weapon against political opponents) and the politicisation of American courts are seen as posing a threat to due process and the rule of law.

It is telling that more than two-thirds of Americans, according to a Quinnipiac University poll, think US democracy is broken. One international study has even designated America a “backsliding” democracy.

Meanwhile, with the shifts in global economic and political power, America’s relative decline is accelerating. The US has only one challenger at the global level, China, which does not hide its ambition to emerge as the world’s foremost power. But through short-sighted policies, including a sanctions-centred approach, the US is inadvertently helping China to accumulate greater economic and military power.

Domestic maladies, for their part, are directly contributing to the decline of US global leadership. Hyper-partisan politics and debilitating polarisation, for example, impede the pursuit of long-term American objectives. In foreign policy, the partisan divide can be seen in divergent perceptions of international challengers to the US: Republicans are most concerned about China, while Democrats worry about Russia above all.

Political malaise at home, by exposing chinks in the US armour, is also fraying America’s global image. As former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott has put it, “a palpable loss of domestic confidence in the US is corroding America’s external projection and potency.”

Lawfare, by laying bare the manipulation of the judicial system by the Justice Department and district attorneys, is backfiring on the ruling Democratic Party by helping to make former President Donald Trump a stronger candidate for the November presidential election. By citing the principle that no one is above the law, Democrats have waged an unprecedented legal offensive against Trump in an effort to derail his candidacy, hoping that the legal system would box him in.

Instead, the different cases against him not only helped Trump cruise to an easy victory in the Republican Party primaries but also have boosted his bid to win the November election. The day Trump was convicted in Manhattan of falsifying records to cover up hush-money payment to a porn star, small donors contributed a record-shattering $34.8 million to his campaign.

The politicisation of the judicial system has raised the spectre of retaliatory Republican lawfare in future. But, fortunately, the recent US Supreme Court decision effectively shielding Trump from prosecution for actions he took as president blocks a future Republican administration from seeking retribution against President Joe Biden. By ruling that a president enjoys immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within his core constitutional duties, and presumptive immunity for other official acts, the judgment protects every president from partisan prosecutors.

However, hardened polarisation and partisan attacks on institutions are contributing to a systemic loss of faith. Consider the Democratic Party’s vitriol against the Supreme Court over its recent judgments on several key issues, including presidential immunity. Or take the alarming poll finding that about one-third of Americans still believe that Biden did not legitimately win in 2020 because the election was rigged.

With India gaining greater salience in American policy, the general trajectory towards closer Indo-US strategic cooperation is unlikely to be altered after Biden is out of office. There is strong bipartisan support in Washington for deepening the US engagement with India. Indeed, the US-India relationship serves as the fulcrum of America’s Indo-Pacific strategy

Even public trust in scientists has declined sharply in the US, thanks to Covid-era excesses, according to a Pew Research Center survey. Nearly 40 per cent of Republicans or Republican-leaning independents have little or no confidence in scientists.

As if all that were not bad enough, the US has finally woken up to the unpalatable reality that its sitting president, Joe Biden, may not be up to the task due to cognitive decline.

But contrary to how the US mainstream media is portraying it, America’s Biden problem did not arise all of a sudden. In fact, the mainstream media was more than complicit in ignoring or obscuring over several years the president’s cognitive decline.

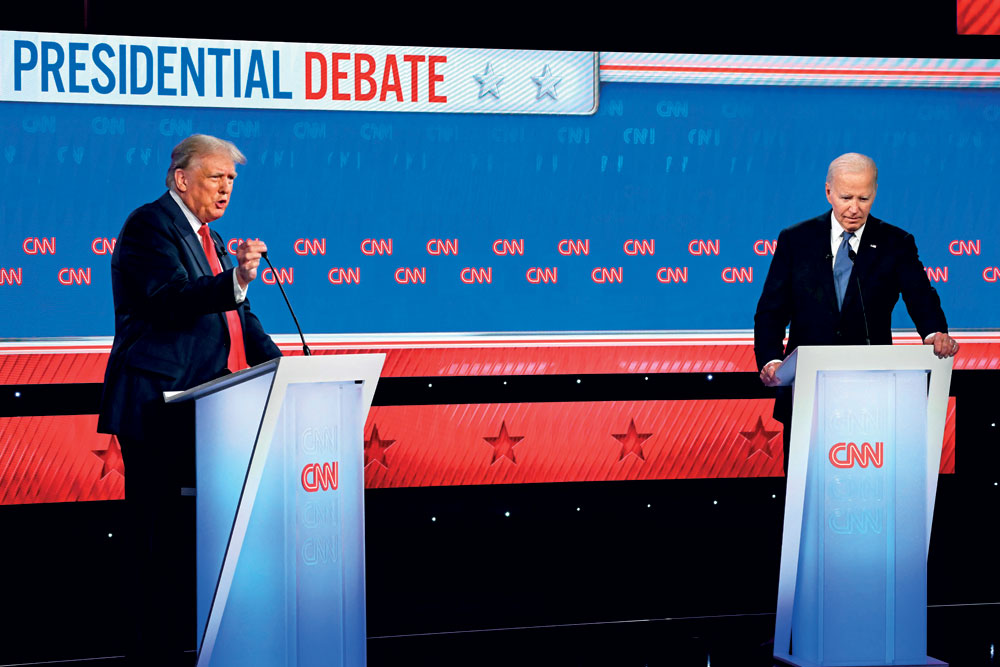

To be sure, Biden performed poorly in his first debate with his political opponent, Trump. Biden repeatedly appeared to lose his train of thought during the June 27 debate. He frequently paused and stumbled over words, struggling to present a coherent and cogent narrative.

Biden’s cognitive issues have been apparent since at least 2020. But the increasingly partisan US mainstream media chose not to report on the state of Biden’s mental health until the decline progressed to such an extent that the president virtually crashed in the debate with Trump. The major media outlets then reacted with shock, as if they had been unaware of Biden’s diminishing physical and mental capacities.

THE LEADERSHIP CRISIS

The American ‘deep state’ has a long record of concealing, with the help of a pliable media, the significant physical or mental disability of a sitting president or a favoured presidential nominee.

Take the example of two icons of the modern Democratic Party, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D Roosevelt, both of whom are still placed in the ranks of America’s greatest presidents.

After President Wilson suffered a paralysing stroke in October 1919 that left him incapacitated until the end of his presidency in March 1921, his wife, despite little formal education, ran the government for the remainder of his term, without the public knowing about it. The wife, Edith Wilson, effectively became America’s first woman president months before women officially won the right to vote in the US.

Roosevelt, a polio survivor, won the presidency by a landslide in 1932 with most Americans unaware that their president had to spend much of his time in a self-designed wheelchair. According to the 2003 book, <FDR’s Body Politics: The Rhetoric of Disability> by academics Davis W Houck and Amos Kiewe, “Roosevelt’s disability was carefully concealed not only from the media, and thus the public, but also from some members of his own family.” The Secret Service was tasked to prevent the press from taking a photograph of FDR in a “disabled or weak” state. Still, FDR won the presidency four times—twice during the Great Depression and twice more during World War II. As Allied forces were nearing victory in World War II, Roosevelt’s health deteriorated steadily before he died of a stroke.

Less than two months after he took office, Biden, while climbing up to board Air Force One, tripped three times on the stairs. But the fall, like other subsequent incidents, was obscured or played down by the mainstream media. In the three-and-a-half years that Biden has been in office, he has grown increasingly frail and forgetful

Against this backdrop, the American mainstream media, in one of the worst journalistic cover-ups in decades, hid from the public Biden’s increasing cognitive decline. Right through his presidency, Biden’s cognitive issues have largely confined him to carefully scripted public appearances.

Without relying on teleprompters and pre-written scripts, Biden not only has had difficulty in publicly articulating his ideas or thoughts or making policy-related comments, but he also has tended to stumble over words and speak incoherently.

The major media outlets turned on Biden only when their cover-up became impossible to sustain. As if acting on cue, the entire mainstream media, after his halting debate performance, began suddenly calling on the president to exit the presidential race.

But more than the poor debate performance, it was polls since May showing that Biden is losing to Trump that set off alarm bells in the ‘deep state’, which is determined to stop the former president from returning to the White House by whatever means possible. This then led to the media just turning on Biden. Now the mounting crisis threatens to topple Biden’s presidency.

The truth is that concerns about Biden’s mental acuity and physical fitness first surfaced during his 2020 presidential campaign, when he limited his campaigning and used teleprompters even for basic stump speeches to small audiences. Those concerns amplified after he entered the White House in January 2021.

Less than two months after he took office, Biden, while climbing up to board Air Force One, tripped three times on the stairs, falling to his knees the third time, despite having his hand on the railing for support. But the fall, like other subsequent incidents, was obscured or played down by the mainstream media. Instead, the major US media outlets ran speculative and baseless stories about Russian President Vladimir Putin being “seriously ill”.

In the three-and-a-half years that Biden has been in office, he has grown increasingly frail and forgetful. Biden’s history of two brain aneurysms, high cholesterol and the heart condition atrial fibrillation are all risk factors for cognitive decline.

Biden’s unscripted public events have been rare. But even at scripted events, Biden has often appeared confused in the past one year about where to exit a podium after having finished delivering prepared remarks. This has led his staff to provide him detailed visual instructions on how to enter and exit a podium.

Meanwhile, Biden’s gaffes have increasingly drawn attention to his declining memory. Earlier this year, for example, he mixed up French President Emmanuel Macron with ex-President François Mitterrand, who died in 1996. Answering a question about the Israel-Hamas negotiations over hostages, Biden appeared confused and disoriented, unable to recall even Hamas’ name. And at a South Carolina rally, he called Trump the “sitting president”.

Yet, scoffing at Republican Party efforts to keep questions about Biden’s mental health front and centre, the US mainstream media insisted since 2021 that there was virtually no evidence to indicate the president was in cognitive decline.

Even Special Counsel Robert Hur’s report that depicted the president as suffering from mental decline was dismissed as a partisan job. The report, released in February, described Biden’s memory as “hazy”, “fuzzy”, “faulty”, “poor”, and having “significant limitations” and said the 81-year-old president displayed “diminished faculties”.

A campaign has begun to replace Biden with vice president Kamala Harris as the presidential nominee. Democratic party strategists are already working to build up Harris, with a leaked ‘case for Kamala’ document stating that the ‘most important priority above all others is defeating Donald Trump’

Despite the media cover-up, ordinary Americans understood the risk to the nation posed by Biden’s diminished physical and mental capacities. Almost a year ago, an important poll found that three-quarters of American adults believed that Biden was too old to effectively serve another four-year term as president. And according to another poll, which was released in May 2023, 62 per cent of respondents said that Biden’s mental competence was a concern.

Yet, to stop Trump, Democrats and the media continued to shield Biden so as to help re-elect him, despite growing evidence that he would not be capable of serving four more years in office. With no real challenger in the primaries, Biden unofficially clinched the Democratic Party nomination as early as March in a process that was much shorter than the one in 2020.

But now the pendulum has swung to the other extreme, with major media outlets going after Biden harshly. They are spearheading a campaign—in breach of media ethics—to force him out.

The New York Times, which claims to strive to maintain the highest standards of journalistic ethics, published a supposedly investigative story on July 2 that said several people who had encountered Biden behind closed doors noticed “he increasingly appeared confused or listless, or would lose the thread of conversations”—the very evidence the newspaper ignored for over four years despite its open availability.

The US media narrative for four years until recently was that America’s big problem is not Biden but the menace to US democracy posed by Trump. Biden himself has hawked the narrative that American democracy hangs in the balance, even declaring that “democracy is on the ballot in the 2024 election”.

Yet, ironically, a Washington Post-Schar School poll released last month showed that over half of American voters in six key battleground states view Biden as a threat to US democracy and not its saviour. Indeed, 44 per cent of the respondents said that Trump would do a better job in protecting American democracy, while only 33 per cent believed Biden would be better. “Those most sympathetic to an authoritarian form of government,” according to the <Washington Post> analysis of the poll, “include demographic groups that have traditionally voted heavily Democratic.”

This is an international reminder that those loudest in claiming that their political rivals pose significant threats to democracy are often perceived by a majority of voters as the real threats to democracy because of their actions. In India, for example, those who oppose even parliamentary references to the draconian 1975-77 Emergency rule claim that the present government, despite recently being elected to a third term, poses a unique threat to Indian democracy.

Today, US Democrats and their media allies, by stepping up pressure on Biden to withdraw, are openly rejecting the result of the primaries. They want to effectively invalidate the 14 million votes Biden received (87 per cent of the total) in a democratic nominating process.

Until Biden’s cognitive impairment started becoming a political liability, the ‘deep state’ was pretty happy with him, as he largely delivered on its demands, including in the Ukraine war. But in the weeks before the debate, Biden’s approval rating began slipping sharply and polls showed that he would lose to Trump. To the ‘deep state’, nothing on Earth is more important than defeating Trump.

Against this backdrop, Biden appears to have outlived his utility for the ‘deep state’ as his impairment makes him a weak candidate against Trump. In keeping with the Anglo-American saying, “Never let a good crisis go to waste,” Biden’s debate performance became a convenient handle to launch a campaign of sustained pressure to make him end his 2024 candidacy.

There is now even quiet discussion on Capitol Hill about whether the constitution’s 25th Amendment could be invoked to remove Biden from office. The amendment permits a president who is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office” to step aside or be removed and have the vice president “immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.”

Trump built a personal rapport with Prime Minister Modi. During his February 2020 visit to India, Trump spoke at the largest rally any American president has ever addressed. Those were the Halcyon days of the Us-India relationship. The Biden administration has sustained the momentum with India. Biden’s personal interactions with Modi have been characterised by ease and warmth

But invoking the 25th Amendment is clearly a long shot. More practically, a campaign has begun to replace Biden with Vice President Kamala Harris as the presidential nominee. Democratic Party strategists are already working to build up Harris, with a leaked ‘Case for Kamala’ document stating that the “most important priority above all others is defeating Donald Trump.”

Until recently, as one prominent American newspaper put it, Harris was “an afterthought and a punchline in the party.” Harris has had a low favourability rating all along. A poll last month showed her to be as risky for the Democrats as the president: Biden at 43 per cent favourable and 54 per cent unfavourable; Harris at 42 per cent favourable and 52 per cent unfavourable.

In this light, what explains the fact that Democrats are starting to coalesce behind Harris as the best option to replace Biden? It is all about money.

The party has contenders whose favourability ratings may be better than Harris, including California Governor Gavin Newsom, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro. But only Harris, as the president’s running mate, would lawfully be able to use the huge funds already raised by Biden’s campaign committee. At the beginning of this month, Biden had $240 million in cash on hand.

If stepped-up pressure eventually forces Biden to exit the presidential contest, it would deny Republicans their weakest opponent, upending Trump’s re-election prospects.

THE POST-BIDEN ERA

With India gaining greater salience in American policy, the general trajectory towards closer Indo-US strategic cooperation is unlikely to be altered after Biden is out of office. There is strong bipartisan support in Washington for deepening the US engagement with India. Indeed, the US-India relationship serves as the fulcrum of America’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Booming American exports to India, the world’s fastest-growing major economy, reinforce such bipartisan support. The US has already become an important source of crude oil and petroleum products for India, the world’s third-largest oil consumer after America and China. And American arms exports to India now run into billions of dollars yearly.

No American administration can ignore the fact that India’s international profile and geopolitical weight are on an upward trajectory. The world’s largest democracy is now the world’s fifth-biggest economy, after surpassing Britain in 2023. By next year, India is set to become the third-largest economy by overtaking both Japan, which is straining to avert recession, and former economic powerhouse Germany, currently the worst-performing developed economy.

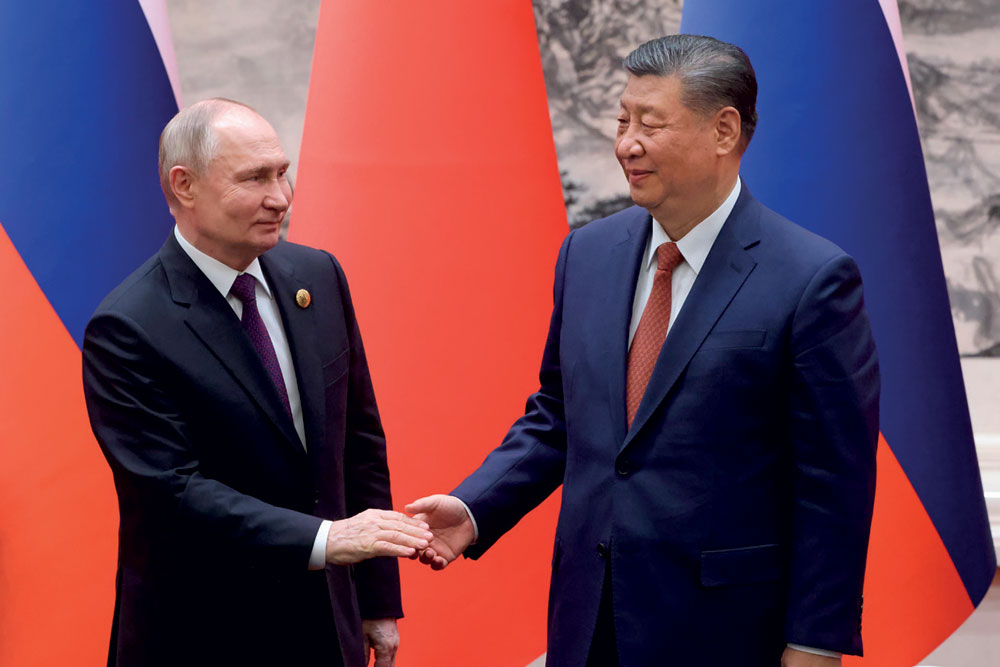

Today, with its global supremacy eroding, the US’ principal adversaries, China and Russia, deepen their entente. Instead of driving a wedge between these two natural competitors, US policy has helped turn China and Russia into close strategic partners

India’s incredible economic growth has made it a crucial pillar of the global economy. India is projected to account for 12.9 per cent of all global growth between 2023 and 2028, more than America’s share of 11.3 per cent.

When Biden unveiled his administration’s “free and open Indo-Pacific strategy” in 2022, it largely mirrored the strategy of his predecessor, Trump. The Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy was declassified in early 2021 just before the Biden administration took office. That declassified document gave India pride of place in American strategy, saying a “strong India” will serve as a “counterbalance to China”. It also committed to “accelerate India’s rise and capacity to serve as a net provider of security.”

Today, with its global supremacy eroding, the US needs India, especially as its principal adversaries, China and Russia, deepen their entente. Instead of driving a wedge between these two natural competitors, US policy has helped turn China and Russia into close strategic partners. If the US is not to accelerate its relative decline through strategic overreach, it has to build closer collaboration with India.

Indo-US relations thrived during the Trump presidency. The Trump administration instituted fundamental shifts in US policies towards China and Pakistan, India’s regional foes, whose strengthening strategic axis imposes high security costs on India, including raising the spectre of a two-front war. In his most lasting legacy, Trump, by instituting a paradigm policy shift, reversed the US policy since the Nixon era of aiding China’s rise. His administration also cut off security aid to Pakistan for not severing its ties with terrorist groups.

Moreover, Trump built a personal rapport with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, with whom he shared a love for big audiences and theatrics. Trump joined Modi’s September 2019 public rally in Houston, attended by 59,000 Indian-Americans and a number of US Congressmen and Senators. Then, during his February 2020 standalone visit to India, Trump spoke at the largest rally any American president has ever addressed—at home or abroad.

More than 100,000 people packed the world’s largest cricket stadium in Ahmedabad as Trump declared, “America loves India, America respects India, and America will always be faithful and loyal friends to the Indian people.” After returning home, Trump called India an “incredible country”, saying, “Our relationship with India is extraordinary right now.” Those were the halcyon days of the US-India relationship.

To be sure, the Biden administration has sustained the momentum in the relationship with India. This has little to do with Vice President Harris’ Indian heritage. The fact is that the Biden administration has recognised India’s centrality in an Asian balance of power. Biden’s personal interactions with Modi have been characterised by ease and warmth.

But the Biden administration has also struck some discordant notes. For example, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it tried in vain to force New Delhi to choose between Washington and Moscow. Biden’s top economic adviser, Brian Deese, crassly threatened that “the costs and consequences” for India would be “significant and long-term” if it refused to take sides. And Biden’s Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, has repeatedly taken a swipe at India over alleged human rights abuses.

It has also become increasingly apparent that America under the Biden administration has no intent to forego the Sikh militancy card that it holds as potential leverage against India. US security agencies continue to shelter and shield Khalistani extremists, despite some of these US-based militants making terrorist threats against India from American soil.

For example, the New York-based militant Gurpatwant Singh Pannun warned Air India passengers last November that their lives were at risk while threatening not to let the flag carrier operate anywhere in the world. Pannun had previously threatened to also disrupt Indian Railways and thermal power plants, according to India’s National Investigation Agency.

Still, the strategic partnership between the US and India is likely to continue strengthening over the long term because it serves both countries’ interests and is pivotal to building power equilibrium in the Indo-Pacific region. The post-Biden era will come with its own opportunities and challenges for India.

You must be logged in to post a comment.