The U.S. today risks accelerating its relative decline through strategic overreach. A first step to addressing that risk is to abandon its sanctions overreach and recalibrate its sanctions so that they stop advancing China’s commercial and strategic interests.

Brahma Chellaney, Nikkei Asia

U.S. foreign policy has long relied on sanctions, despite their uncertain effectiveness and unintended consequences. No sooner had President Joe Biden assumed office than he slapped new sanctions on Russia and Myanmar.

Sanctions are a favorite and grossly overused tool of American diplomacy when dealing with countries that cannot impose significant costs in reprisal. Indeed, Washington has fallen into a self-injurious trap by viewing sanctions as the easy answer to any problem.

Sanctions may have been a defensible policy in the second half of the 20th century, when American economic and military power was overwhelming. But with relative U.S. wealth and power in decline, so is the efficacy of its sanctions. Far from exacting a serious penalty, U.S. sanctions often advance the commercial and strategic interests of its main competitor, China.

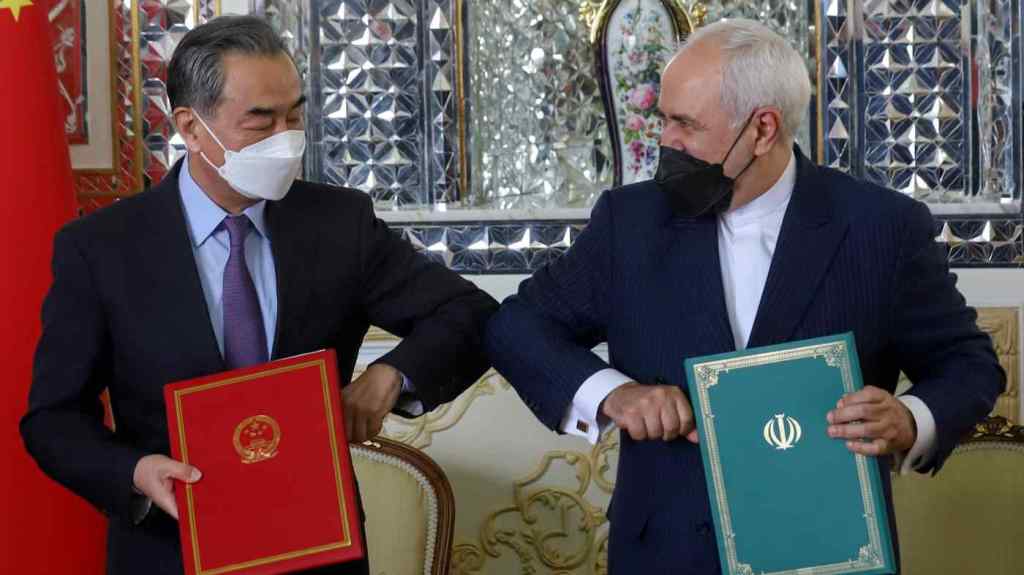

Nothing better illustrates this fact than China’s latest 25-year economic and security agreement with Iran, where ever-tightening U.S. sanctions have made China that country’s most important commercial partner over the past decade.

Now, under the new accord, China will boost its investment in major Iranian sectors even further, step up defense cooperation and establish a joint bank that will allow Tehran to borrow and trade in yuan, whose international use Beijing is actively promoting. Iran also shows how U.S. sanctions can penalize America’s own friends such as India and Japan.

While India’s compliance with America’s Iran-oil embargo has added billions of dollars to its fuel import costs, China has defiantly stepped up its purchases of Iranian oil at discounted prices. When the U.S. reimposed a new list of penalties on Iran in November 2018, it forced many Japanese companies to suspend their contracts with Iranian energy suppliers.

U.S. policymakers should be most worried by how their punitive actions have forced Russia to pivot to China, helping two natural competitors become close strategic partners. A forward-looking U.S. administration would avoid confronting Russia and China simultaneously, and instead seek to play one off against the other.

But Biden, claiming that a declining Russia poses “just as real” a threat as the powerful, rising, technologically sophisticated China, hit Moscow with new sanctions in early March for detaining dissident Alexei Navalny. And, subsequently vowing that Russian President Vladimir Putin will “pay a price” for his alleged meddling in U.S. presidential elections and calling him a “killer,” Biden has threatened to impose more severe boycotts.

The multiple rounds of U.S. sanctions since Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea have already resulted in the worst relationship Washington has had with Moscow since the fall of the Berlin Wall. And as former Defense Secretary Robert Gates recently noted, sanctions “are not going to do much good.”

In fact, Russia’s increasingly close strategic alignment with China represents a profound U.S. foreign policy failure, underscoring the counterproductive nature of American sanctions. The U.S. could seek to rebalance its relationship with Russia by easing its heavy-handed approach, but old habits die hard. More sanctions on Moscow will only strengthen China’s hand in challenging America’s global preeminence.

Paradoxically, the U.S. treats China with respect. Biden, for example, has not called Chinese President Xi Jinping a “killer” or pledged to make him pay a price, despite China’s concentration camps in Xinjiang that hold more than a million Muslim Uighurs. U.S. sanctions over the muzzling of Hong Kong’s autonomy in violation of a United Nations-registered treaty have spared those in Xi’s inner circle.

When it comes to the small kids on the block, however, U.S. sanctions often substitute for forward-thinking policy. For example, the U.S. slapped sanctions on Myanmar’s top generals in late 2019 over the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya instead of addressing what American officials recognized as the main weakness in policy — Washington’s failure to establish close ties with Myanmar’s military.

The sanctions effectively removed all incentives for the commander in chief of Myanmar’s armed forces, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, to support continued democratization. Worse still, after helping turn National League for Democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi into a virtual saint, the U.S. began slamming her over treatment of the Rohingya exodus and her ties to the military, emboldening the generals to stage a coup.

Now the U.S. risks repeating history. Just as crippling sanctions from the late 1980s pushed a reluctant Myanmar into China’s arms, the new series of sanctions on Myanmar since February — including the latest suspension of trade relations — is welcome news for Xi’s regime.

More fundamentally, Washington’s reliance on sanctions has highlighted the inherent weakness in its policy: The failure to develop objective criteria on the circumstances that would justify sanctions has allowed narrow geopolitical considerations to drive the imposition of sanctions seemingly at random.

Why, for example, does the U.S. readily do business with Thailand, even as the leader of the 2014 coup remains ensconced in power, but insists on “immediate restoration of democracy” in neighboring Myanmar? The Biden administration has initiated an internal review of U.S. sanctions programs to understand their utility and consequences. Yet, without waiting for the outcome of the review, Biden has taken to sanctions like a duck to water.

The U.S. today risks accelerating its relative decline through strategic overreach. A first step to addressing that risk is to abandon its sanctions overreach and recalibrate sanctions so that they do not aid Xi’s hegemony-seeking “Chinese dream.”

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and author of nine books, including “Asian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India and Japan.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.