By Brahma Chellaney, The Hill

Bangladesh’s recent descent into lawlessness poses a foreign policy challenge for President Trump, especially because his predecessor supported last August’s regime change there.

The world’s most densely populated country (excluding microstates and mini-states) risks sliding into jihadist chaos, threatening regional and international security.

Bangladesh has also emerged as a sore point in U.S.-India relations, with the issue likely to figure in Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s discussions with Trump at the White House this week. New Delhi is smarting from the overthrow of Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s India-friendly government and the installation of a new military-chosen “interim” administration with ties to Islamists whom India sees as hostile.

The new regime is led by the 84-year-old Muhammad Yunus, who publicly lamented Trump’s 2016 election win as a “solar eclipse” and “black day.” Yunus received the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize after former President Bill Clinton lobbied for him, a fact the Norwegian Nobel Committee chairman acknowledged in his award ceremony speech.

Megadonor Alex Soros — who says that “Trump represents everything we don’t believe in” while vowing to “fight back” — has pledged continued support to the regime in Bangladesh, where he recently went by private jet to meet Yunus, despite the country’s downward spiral into violent jihadism. This was his second meeting with Yunus since September, when the two met in New York.

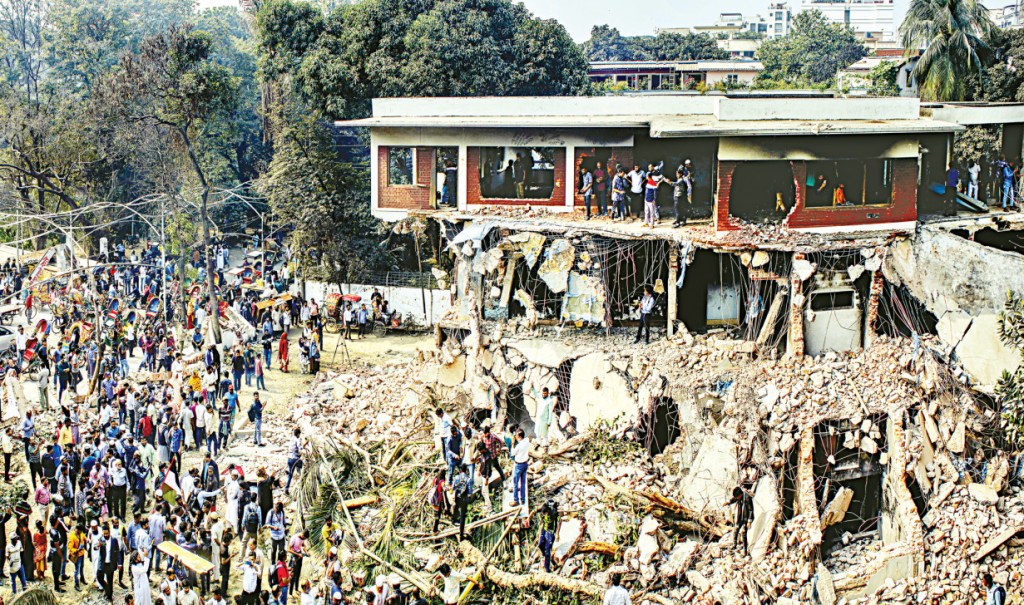

The lawlessness in Bangladesh was on stark display last week as regime supporters went on a rampage, setting ablaze or demolishing properties in a coordinated manner, including the national memorial to Hasina’s assassinated father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the country’s charismatic founding leader. Mobs also looted and burned down Hasina’s private residence and the homes of several leaders of her Awami League party.

In a sign of regime complicity in the attacks, security forces stood by and watched quietly as mobs ran amok, including storming the memorial museum, where the country’s independence was proclaimed in 1971. The attackers, after failing to burn down the memorial with the fire they lit, brought excavators and manually tore down the memorial over two days, prompting Islamist celebrations at the site with an Islamic State banner. Only after the various attacks were over did Yunus appeal for calm.

The razing of the memorial museum, which was originally the founding leader’s residence and where he and much of his family were murdered in a 1975 predawn army coup, could help advance the current regime’s effort to redefine or erase key aspects of Bangladesh’s history. In fact, this was the second assault on the memorial since the regime change, with the first attack leaving it partially damaged and without family archives owing to looting and arson.

Last week’s spate of attacks across the nation showed why the regime, as Bangladeshi media highlighted, is struggling to restore law and order or reverse the downturn in a once-booming economy, which, under Hasina’s secular government, lifted millions of people out of poverty. Now, as foreign reserves plummet and foreign debt spirals upward, the country is seeking international bailouts.

Since its first coup in 1975, which led to more military interventions and counter-coups, Bangladesh has remained trapped in a cycle of violence and deadly retributions. The military-backed ouster of Hasina — the “iron lady” who kept both the military and Islamist movements in check, but who lurched toward authoritarianism — followed weeks of student-led, Islamist-dominated violent protests.

After police fired on rioting protesters, mobs captured dozens of policemen, beating them to death and hanging the bodies of some from bridges. A total of 858 people reportedly died in what the Yunus regime and its supporters have called a “revolution.” The military used the violence to pack Hasina off to neighboring India before she could even resign.

Violence, however, has only escalated under the Yunus administration, especially against political opponents, religious and ethnic minorities, and anyone seen as a critic of the regime. Just days before the American election in November, Trump posted, “I strongly condemn the barbaric violence against Hindus, Christians, and other minorities who are getting attacked and looted by mobs in Bangladesh, which remains in a total state of chaos.”

Islamist violence has gained ground largely because Yunus has lifted bans on jihadist groups with links to terrorism and freed violence-glorifying Islamist leaders. Hundreds of Islamists have escaped from prisons. Extremist groups — including Hizb ut-Tahrir, proscribed by several Western governments as an international terrorist threat — now operate freely in Bangladesh, from demolishing shrines of minorities to staging anti-Trump marches.

In fact, a dysfunctional Bangladesh is becoming a mirror image of its old nemesis, Pakistan, from which it seceded following a bloody war of liberation that left up to 3 million civilians dead in a genocide led by the Pakistani military.

Given the country’s porous borders, the current violence and chaos in Bangladesh affect India’s security. Already home to millions of illegally settled Bangladeshis, India faces growing pressure on its borders from those seeking to flee religious or political persecution in Bangladesh. Fearing infiltration by freed terrorists, India has sought to tighten border security. A lawless Bangladesh is also not in America’s interest.

As Trump seeks to build on his rapport with Modi to restore America’s fraying relationship with India, a shift away from the Biden policy of mollycoddling the Yunus regime could help ease Indian security concerns. If the U.S.-India strategic partnership is to advance a stable balance of power in Asia, the two powers must work in sync with one another in India’s own neighborhood to help build mutual trust.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and the author of nine books, including the award-winning “Water: Asia’s New Battleground.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.