Brahma Chellaney, Nikkie Asian Review

As a bridge between Asia and Europe, the Indian Ocean has become the new global center of trade and energy flows, with half the world’s container traffic and 70% of its petroleum shipments traversing its waters. But there is a very real danger of this critical region becoming the hub of global geopolitical rivalry.

The region includes the entire arc of Islam, extending from the Indonesian archipelago to the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Competition between key political powers for its resources is intensifying, even as threats to maritime security grow.

A fragile center?

According to several assessments, including a study by Harvard’s Center for International Development, the Indian Ocean Rim is likely to eclipse the Pacific Rim as the most important economic region in the world.

Growth in China and developed economies is slowing, and India and East Africa are expected to become the new drivers of global growth over the next decade. As a result, the Indian Ocean region will likely become both a global maritime hub and an economic growth center — and as such strategic jockeying by great powers will undoubtedly increase in the years ahead.

At the same time, the region also has the world’s largest concentration of fragile or failing states — from Yemen and Somalia to Pakistan and the Maldives. Moreover, it is wracked by the world’s highest incidence of transnational terrorism. Security in the Indian Ocean is a pressing concern given the increasing importance of its maritime resources and sea lanes.

The region’s rim states may share a number of common interests — sea-lane security, environmental protection, regulated resource extraction, and rules-based cooperation and competition, to name a few — but they are far from becoming a community with common values. In fact, in no part of the world is the security situation so dynamic as it is along the Indian Ocean Rim.

Against this background, threats to navigation and maritime freedoms are increasing.

One source of threats comes from cross-border disputes related to maritime boundaries, sovereignty and jurisdiction. Myanmar and Bangladesh, and India and Bangladesh, have set an example by peacefully resolving their maritime-boundary issues through international adjudication or arbitration. But unresolved disputes involving other countries in the region carry serious potential for conflict.

Several states restrict freedom of navigation in their exclusive economic zones while engaged in military activities, such as surveillance by ship. The threats to navigation and maritime freedom in the Indian Ocean can be countered only through adherence to rules agreed upon by all parties and through monitoring, regulation and enforcement.

Challenges of gatekeeping

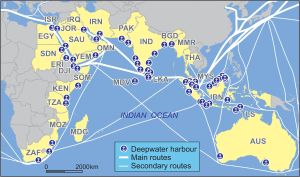

Another regional concern centers directly on sea-lane security, given the Indian Ocean’s importance to global trade and energy flows and the potential vulnerability of the chokepoints around it. These chokepoints include the Strait of Malacca, situated between Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, the Strait of Hormuz, between Iran and Oman, the Horn of Africa, between Djibouti, Eritrea and Yemen, and the routes to and from the Cape of Good Hope through the Mozambique Channel.

Safeguarding the various gateways to the Indian Ocean is thus a vital security issue, and outside powers have sought to secure these points by pursuing strategic cooperation with key coastal states. Such cooperation extends to naval training, joint military exercises and anti-piracy operations.

At the same time, the paucity of land-based natural resources in the Indian Ocean Rim has stoked competition over ocean resources, such as seafood and mineral wealth.

Deep seabed mining has emerged as a major new strategic issue and competition over such minerals is intensifying. Even an outside power like China has secured a block in the southwestern Indian Ocean from the International Seabed Authority to explore for seabed minerals.

At stake is a treasure trove of minerals, from sulfide deposits containing valuable metals such as silver, gold, copper, manganese, cobalt and zinc, to phosphorus nodules, mined for the phosphor-based fertilizers used in food production. The competition for these resources underscores the need for a regulatory regime that ensures environmental protection and safeguards the region’s common heritage.

The Indian Ocean region is a microcosm of the global challenges of the 21st century. In addition to terrorism, piracy and other threats to the safety of sea lanes, those challenges extend into nontraditional maritime-security domains.

For example, 70% of the world’s natural disasters occur in the Indian Ocean Rim, typically floods, cyclones, droughts and tsunamis, but also geological events such as earthquakes and landslides. These disasters present a high humanitarian risk.

No less significant is the fact that the region is on the front line of climate change. It has states whose very future is imperiled by global warming, including the Maldives, Mauritius and Bangladesh. With many megacities, energy plants and industries located in densely populated areas near the sea, the vulnerability of its coastal infrastructure has emerged as an important concern.

Put simply, this is a region where old and new challenges converge. It is also a place where the old world order — as epitomized by the Anglo-American military base at Diego Garcia and the French-administered islands — coexists uneasily with the emerging new order.

Power plays

Great-power rivalries are clearly compounding maritime-security challenges in the Indian Ocean. India may be the largest local power, but China has started challenging it in its maritime backyard. In response, India is working to revive linkages along the ancient spice trading route that once stretched from Southeast Asia to Europe, with southern India as its hub.

China has become the most active outside player in the region and is challenging the existing balance of power. This is in keeping with the greater maritime role it is openly seeking for itself. Its newly released defense white paper says that the Chinese navy will shift focus from “offshore waters defense” to “open seas protection.” One example of China’s increasing interest in the Indian Ocean is its move to set up a naval base in Djibouti, which overlooks the narrow Bab al-Mandeb straits.

Determined to take the sea route to world-power status and challenge the U.S.-led order, China is likely to step up its strategic role in the Indian Ocean. These ambitions are reflected in China’s submarine forays there since last autumn and in its Maritime Silk Road trade route initiative. Whether this “Maritime Silk Road” is just a benign-sounding new name for China’s “string of pearls” strategy is an important question that cannot be dismissed.

There are other maritime-security issues in the Indian Ocean as well. For example, some important players, including the United States and Iran, are not yet party to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS. China is a party, but it refused — in a case brought against it by the Philippines — to accept the convention’s dispute-settlement mechanism, as represented by the Hamburg-based International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. In 2013, Iran seized an Indian oil tanker and held it for nearly a month, but India had no recourse, as Tehran had not ratified UNCLOS.

In this light, the 1971 U.N. General Assembly resolution declaring the Indian Ocean a “zone of peace” has become more important than ever. Indeed, in coming years, the Indian Ocean is likely to determine the wider geopolitics, maritime order and balance of power in Asia, the Persian Gulf and beyond. Developments in East Asia, where the power balance is unlikely to fundamentally change, will likely be of less importance than those in the Indian Ocean Rim, where the power balance is under threat.

Given this reality, the U.S., Japan, India, Australia and other important players must recalibrate their Indian Ocean policies and put greater focus on ensuring peace, safeguarding sea lanes and guaranteeing access to the global commons.

Brahma Chellaney is a geostrategist and author of nine books, including the award-winning “Water: Asia’s New Battleground.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.