By Santha Oorjitham

New Straits Times, May 25, 2011

Tension over precious water resources in Asia is already rising, warns Brahma Chellaney in an interview with SANTHA OORJITHAM

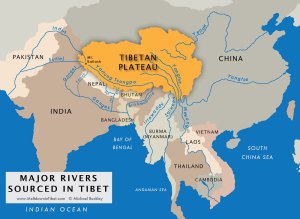

Q: The Tibetan plateau supplies water to 47 per cent of the world’s population. How would you rate cooperation between upstream and downstream countries on managing water resources?

A: There are treaties among riparian neighbours in South and Southeast Asia, but not between China and its neighbours.

For example, the lower Mekong states of Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam have a water treaty. India has water-sharing treaties with both the countries located downstream — Bangladesh and Pakistan.

There are also water treaties between India and its two small upstream neighbours, Nepal and Bhutan. But China, the dominant riparian power of Asia, refuses to enter into water-sharing arrangements with any of its neighbours.

Yet China enjoys an unrivalled global status as the source of trans-boundary river flows to the largest number of countries, ranging from Vietnam and Afghanistan to Russia and Kazakhstan.

Significantly, the important international rivers in China all originate in ethnic-minority homelands, some of them wracked by separatist movements. The traditional homelands of ethnic minorities, extending from the Tibetan Plateau and Xinjiang to Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, actually span three-fifths of the landmass of the People’s Republic of China.

Q: What are the main sources of water stress in the Asia-Pacific region?

A: Many of Asia’s water sources cross national boundaries, and as less and less water is available, international tensions will rise.

The sharpening hydropolitics in Asia is centred on international rivers such as the Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Brahmaputra, Mekong, Salween, Indus, Jordan, Tigris-Euphrates, Irtysh-Illy, and Amur. There is also the stoking of political tensions over the resources of transnational aquifers, such as al-Disi, which is shared between Saudi Arabia and Jordan, or the ones that link Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories.

Q: Are there intra-state tensions over location and approval of dam sites?

A: Intra-state water disputes are rife across Asia. The more democratic a country, the more raucous the intra-country water disputes tend to be.

In repressive political systems, water protests are quickly muffled. Yet China is discovering the hard way that it is difficult even for an autocracy to fully suppress grassroots protests over new water projects that displace residents or over diversion of water from farmlands to industries and cities.

Q: You have also written about possible interstate tension over reduced water flows. Has this already happened?

A: According to the United Nations, growing competition over water resources has “led to an increase in conflicts over water” in Asia between provinces, communities, and countries. Asia illustrates how rapid rates of population growth, development, and urbanisation, together with shifts in production and consumption patterns, can place unprecedented demands on water resources, bringing them under growing pressure and fostering domestic discord.

Water conflict within nations, especially those that are multiethnic and culturally diverse, often assumes ethnic or sectarian dimensions, thereby accentuating internal security challenges.

If the feuding provinces or areas are ethnically distinct, their water dispute also rages along ethnic lines. This pattern has been most visible on the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia and between Han settlers and ethnic minority people in Xinjiang.

In Central Asia, much of the freshwater comes from the Pamir and Tian Shan snowmelt and glacier melt that feed the region’s two main rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. The resources of these two overexploited rivers have become the target of appropriation and competition.

One of the underlying causes of the mid-2010 bloody riots in the Fergana Valley — a minefield of religious fundamentalism and ethnic animosities — was the local ethnic-Kyrgyz fear that Uzbekistan wanted to absorb that water-rich region of Kyrgyzstan.

Q: What are the policies and strategies you suggest in “Water: Asia’s New Battleground” (to be released in Asia in June) to prevent “water wars”?

A: The water crisis and competition test Asia’s ability to forge a more cooperative future. How Asia handles this challenge will shape not only its water future, but also its economic and political future.

Given that Asia has the fastest-growing economies and the fastest-rising demand for food, its water shortages will only worsen without major efficiency gains in use.

Three strategies are specifically recommended.

The first is to build Asian norms and rules that cover trans-boundary water resources. The second is to develop inclusive basin organisations encompassing transnational rivers, lakes, and aquifers in order to manage the water competition.

And the third is to develop integrated planning to promote sustainable practices, conservation, water quality, and an augmentation of water supplies through nontraditional sources.

Q: Should water be “securitised”?

A: Whether we like it or not, the “securitisation” of water resources has been going on for years. Indeed, in a silent hydrological warfare, the resources of transnational rivers, aquifers, and lakes have become the target of rival appropriation, with these watercourses being treated as national-security assets.

Water has become an important security issue in several important bilateral relationships in Asia, including those between China and India; between China and the other Mekong River basin states; and among states in South Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia.

Singapore also “securitised” the water issue, using its concerns over a potential Malaysian cut-off of water supply to build a stronger military capability.

Brahma Chellaney, professor at New Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research, will be speaking at the 25th Asia Pacific Roundtable next week